Listen to David read this article

Some 30 years ago I found myself working with David Pritchard, a director who turned the late Keith Floyd into a TV star.

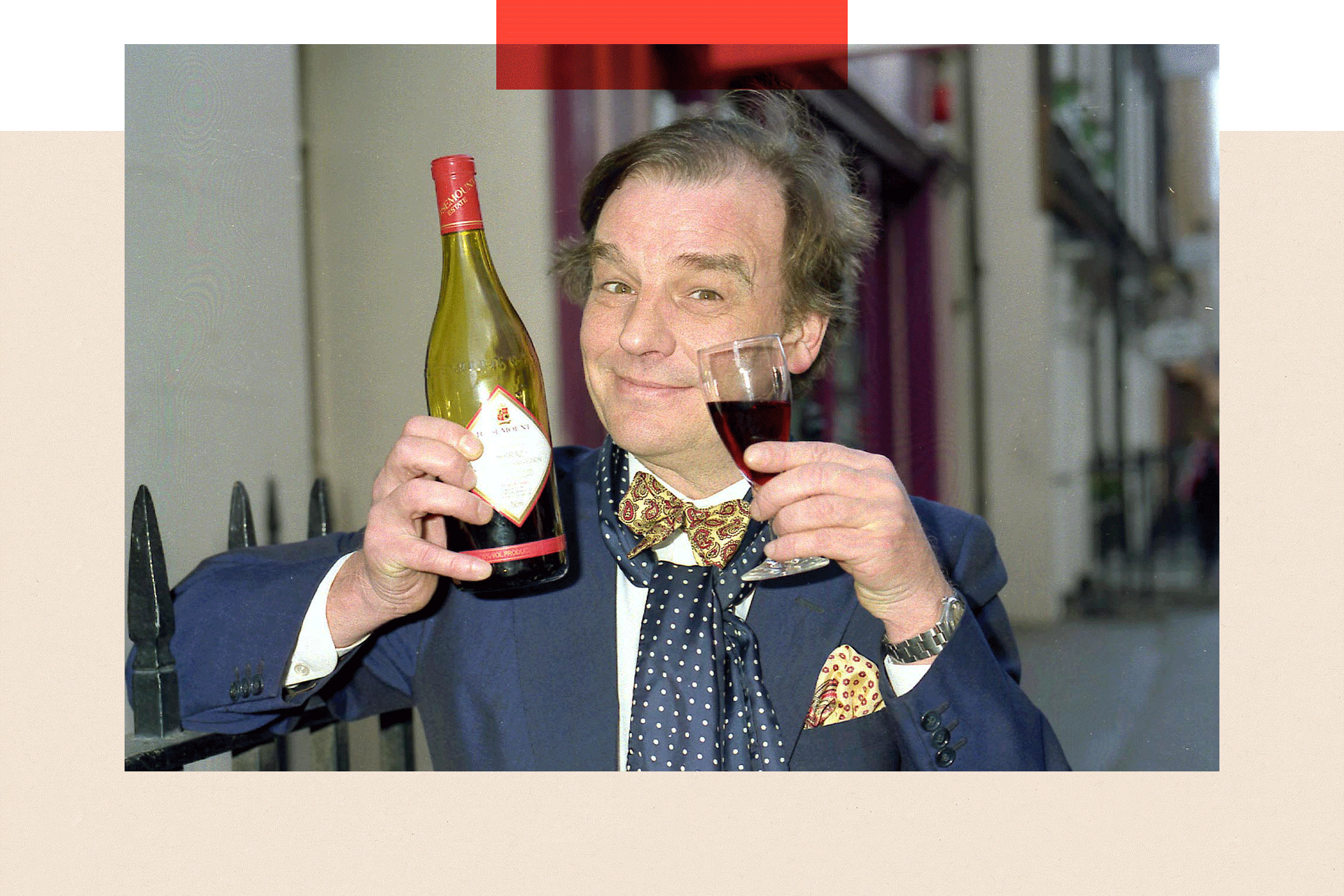

He had first encountered Floyd, glass in hand, chaotically running a Bristol restaurant and coaxed him into cooking on television, often, it appeared, semi-sloshed, on a trawler or a gale swept hillside or, memorably, in a field of ostriches.

Audiences loved it. More than 20 television series ran with Floyd at the helm, and one of the attractions was the obvious tension between him and his director.

It was never going to end well.

One day, while we were editing a programme, David walked in fresh from filming with Floyd. He looked pained. "We flew back on separate planes," he said.

Then he leant closer and told me he didn't have to worry: "Rick will save me."

TV once turned out stars like Fanny Craddock, Delia Smith and Keith Floyd. That conveyor belt has slowed

Rick Stein had appeared on Floyd on Fish. He was given his own cooking show and went on to host dozens more, including 40 episodes of Rick Stein's Cornwall.

Meanwhile, the light sprinkling of food shows of the early 90s went on to become a daily staple of TV schedules throughout the 2000s and 2010s.

In 2014, there was a complaint that the BBC had, in one week, broadcast 21 hours of cooking shows.

Then, seemingly just as abruptly as it all began - it was all over.

Shows known in the industry as "stand and stir" fell off a cliff this year. The number of new, half-hour shows from the BBC so far this year: zero.

Commissions for all forms of food programmes across British TV have dropped 44% in a year, according to Ampere Analysis.

Elsewhere, however, food videos are booming - only they're not made by traditional production companies. Instead, they are on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok.

Rick Stein had appeared on Floyd on Fish. He was later given his own cooking shows

In February, the ratings agency Nielsen reported a landmark moment: YouTube is now the most-watched service on American TVs. We're not talking about phones or laptops but TVs. The UK is not far behind.

By July, the broadcasting regulator Ofcom had published a report warning that British TV is facing a crisis. "Time," it said, "is running out to save this pillar of UK culture and way of life."

Cristina Nicolotti Squires oversees TV in the UK for Ofcom. "Unless something is done soon, this great broadcasting culture and landscape is under threat."

This is true of many types of television. Zuzana Henkova of Ampere Analysis gathers data on UK production and says there is a consistent decline in commissioning for documentaries, art and culture, historical, travel, sport and nature.

But the biggest drop over the last 12 months was for cooking.

Even some of the most popular TV cooks, like Nigella Lawson, are off the TV menu in the UK for now

Even some of the most popular TV cooks, like Nigella Lawson and Nadiya Hussain, are off the TV menu in the UK for now. The question is, why?

What is it that has made us fall out of love so spectacularly - and so suddenly - with what was once one of our favourite genres, and what is it about food influencers in particular that have eclipsed the popularity of the once-beloved "chop and chat" stalwarts?

Millions of views vs 'proper' TV

Natalia Rudin used to be a private chef but a video she shared on Instagram in January 2023 of an "antipasti-style bean dish" with olives, artichokes, sun-dried tomatoes and "a sort of white wine sauce" changed everything.

"I posted it and didn't really look at my phone and then… the next day, it had over a million views," she recalls.

"It was wild," she says. She admits she hadn't even been very happy with the video: "I was a bit hungover from New Year."

Today she has 1.5 million followers as Natsnourishments and is known as "the bean queen".

Today Natalia Rudin has 1.5 million followers as Natsnourishments

When sales of tins and bottles of beans rose 122% in Waitrose in a year, they put it down to foodie influencers, like Natalia. She no longer only posts on Instagram but on YouTube too. Some of her Instagram videos have surpassed 20 million views.

Now she's thinking about where to go next.

"I wouldn't say no to TV but… YouTube's where it's at," she says. "I like it because I have a little bit more control over it and I can decide what goes out."

Other food influencers tell a similar story.

When Ben Ebbrell was training as a chef, his school friends would text him, asking how to cook basic dishes. Now, his channel, Sorted Food, has 2.89 million subscribers and earlier this year he attended a reception at 10 Downing Street for leading YouTube creators.

"It was," he says, "a bit of a pinch-me moment."

'TV is kind of coming to the content creators and saying: We'd quite like your audience,' says Ben Ebbrell of Sorted Food

The figures are impressive, with 1.3 billion views - but surely, I ask, he'd prefer to make a "proper" TV programme?

He pauses. This question has clearly come up before.

"[In the past] it was very much if you want to come and play in our TV world you have to play by our rules, whereas now TV is kind of coming to the content creators and saying: 'We'd quite like your audience to come use our platform, too.'"

The legend of the cronut

The reason for all of this seems straightforward enough. For Ben Ebbrell, it comes down to the cronut.

A few years ago, he says, his channel was "inundated" with comments from people in New York about this new craze - a cross between a croissant and a donut.

So, he recalls, they found some cronut photos online, came up with a recipe, made a video and published it.

"Every newspaper was writing about it and there was only one video on YouTube of how to make it and that was ours, and we were able to be nimble only because our community steers our content."

Ben Ebbrell recalls when his channel was swamped with comments from New Yorkers obsessed with the cronut

This is not how TV programmes are made. It's a world of pitches, focus groups and meetings - the online video world has almost none of that.

According to Ed Sayer - a veteran producer and commissioner who writes as The TV Whisperer - food is a perfect example of TV's problem.

"Television is heavily regulated, so you have lots of compliance," he says. There will be a team checking recipes haven't been copied from a recipe book, for instance.

By contrast, he says, the "abundance" of creators on YouTube and TikTok "don't have those same compliance issues".

Lower costs, greater freedom and an explosion of creative ideas have also helped change the game. We may think of YouTube as a "creative community" - it's not. Today there are 115 million channels on it - that makes it a "creative nation".

But dig deeper and this is about far more than regulation and red tape, or even the speed to react to trends - the real challenge is cultural.

Like the arrival of rock and roll

As far back as 2008, the then-chairman of ITV, Michael Grade called services such as YouTube "parasites" who did not create TV, just lived off it. It's true, they were not making TV - they were making something revolutionary.

Videos of make-up tutorials, pranks, unboxing products - and lots of cooking. None of this was seen as competition for "professionally made" programming.

And so for years many continued to underestimate it.

In August 2013, Kevin Spacey gave a speech at the Edinburgh TV Festival. Netflix, at the time, had around 1.5 million subscribers in the UK. He was the star of House of Cards and his message was simple. TV had won.

But my other memory from that year's festival was a session led by YouTube. Fellow media journalists and I were sceptical - surely YouTube wasn't television, but a place for low-quality home videos?

In 2014, The Times wrote that industry analysts were sceptical that "low-budget, short-form videos" would ever seriously challenge television's dominance.

Fanny Cradock appeared on TV cooking shows including Kitchen Magic and Fanny's Kitchen

Even now, there's a degree of disbelief in some quarters. In a recent conversation on LinkedIn by some TV professionals, one poured scorn on young people on TikTok and YouTube for "not knowing" how to use clip-on mics.

But it's not that they don't know how to; they just don't want to.

It's a little signal to the rest of the online world that this isn't the fake world of television, this is raw and real.

Ed Sayer says younger people like this "rough and readiness" - and when they watch television, their reaction is typically: "It's so false and fake."

Why Bake Off broke the mould

Some in TV have long understood the importance of authenticity.

Take the one type of food programme that is still a prime-time attraction - the cooking competition, like Masterchef or the Great British Menu.

Masterchef remains a part of prime time, despite its well-publicised troubles leading to the departure of hosts Gregg Wallace and John Torode.

And then there's the ratings show-stopper of food TV, The Great British Bake Off.

Richard McKerrow, the co-creator of Bake Off, always believed authenticity was the key ingredient, but says it was a struggle for others to see this too.

"I pitched Bake Off for five years and they told me it'd be like watching paint dry," he says. "No one wanted it."

Richard McKerrow, co-creator of Bake Off, says authenticity was always vital, though it wasn't always easy to convince others

Only when filming began did the magic reveal itself, he says. "I was going, 'Oh my God, these bakers aren't paying any attention to the camera because what they care about is what Paul [Hollywood] and Mary [Berry] think of their cake.'"

It tells you something that Bake Off was seen as a huge risk before it first broadcast in 2010, at a time when TV had rather more spending power - and the last 15 years has seen no successful rival take off. People are going elsewhere with their ideas.

Much of what's left of food TV is now funded by brands and outside agencies. On ITV, Tom Kerridge Cooks is sponsored by Marks and Spencer and features "producers who supply M&S" - so too does Cooking With the Stars.

More than 20 television series ran with Keith Floyd at the helm

Judi Love's food show is backed by Emerald Cruises, Dermot O'Leary's is part-funded by Tourism Ireland; Gary Barlow's latest is backed by Tourism Australia and Hays Travel. Anna Haugh's Big Irish Food Tour is financially supported by Tourism Ireland.

But overall, the conveyor belt that brought us Fanny Craddock, Delia Smith and Keith Floyd has stopped.

The question is, does it matter if more disappear?

Did food shows change the way Britain eats?

Some argue food shows helped change the way Britain eats - they have also taken us into homes and kitchens around the world.

Ken Hom and Ching He Huang's travel and cooking series in 2012 was a fascinating snapshot of life in China through the lens of food.

But 13 years on, the money for such programming just isn't there.

Of course, YouTube has a wealth of travel and observational content. But there are 69,000 YouTube channels with more than a million subscribers; money and attention are spread thin.

Ken Hom (pictured) and Ching He-Huang's 2012 travel and cooking series offered a vivid look at life in China through its food

Jonathan Glazier, a TV executive and writer who has worked on dozens of shows including the Generation Game and Gladiators, expresses his sadness at the slow disappearance of TV's shared moments. Especially, he adds, the programmes that capture real people as they puzzle, struggle and laugh their way though life.

"That's what television is," he argues, "it's about the characters that populate this country.

"The more we lose this type of storytelling, the more we become strangers to ourselves."

However, while TV may be facing a tough challenge, our appetite for video is not dying.

Ed Sayer, for one, is hopeful. "Audiences don't care about platforms - they care about stories, authenticity, and relevance," he says. Success will come down to who understands the new landscape best.

"Ultimately," he says, "YouTube isn't winning and TV isn't winning. The audience is."

More from InDepth

Why luxury cheese is being targeted by black market criminals

- Published10 November 2024

How Russia is quietly trying to win over the world beyond the West

- Published25 August

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.