Immigration in a Red Wall English county

Len Burkitt, who is almost 80, works at a local Co-op

- Published

Immigration is a key issue on the campaign trail this general election. The BBC spoke to voters on the streets of Staffordshire, as well as asylum seekers who have escaped persecution to live there.

"Immigration doesn’t affect me that much but it's got to stop because it's costing the public too much money," Len Burkitt says.

"Taxes are going up, cost of living is going up and we're supporting them but, you know, they're desperate for somewhere better to live, I suppose.

"But the boats have got to stop, that’s my opinion."

Len lives in Stafford, one of Staffordshire's historic market towns.

It made headlines last year when more than 250 people objected to plans to house 481 asylum seekers in a former university halls of residence, a series of public meetings sparking protests by banner-waving campaigners.

Initially refused by Stafford Borough Council, a planning inspector ruled Serco could go ahead with the proposals. The site lies empty, for now.

Objectors said they feared pressure on health services, among a long list of other concerns.

"The NHS is a worry for me," says Len, echoing the views of many voters who have shared their thoughts with the BBC in recent weeks.

"I'm old, I'm nearly 80 now and I can't even get an appointment."

Serco wants to house 480 asylum seekers in this old halls of residence in Stafford

Immigration is a key issue as the general election looms, with the main political parties differing widely on how they plan to control numbers of people hoping to settle in the UK.

At the 2019 election, it was high on the agenda then too. And Staffordshire, many parts of which were once staunch Red Wall, Labour-voting seats, turned Conservative blue in many for the first time ever.

Latest figures show more than 2,800 immigrants are in the county. This includes refugees from Ukraine and Afghanistan, as well as those the government has put up in hotels to ease an accommodation crisis.

Hotels in Burton, Stafford and Cannock were among those closed to the public to house asylum seekers, while in Stoke-on-Trent, the council lost a High Court bid to stop a city centre hotel being used.

Figures published in March showed there were still 1,133 living in hotel accommodation in the city, one of the highest figures in England.

For Roger Pearhouse, again it's the cost of accommodating migrants who have arrived in the UK illegally and pressures on local services that is a real worry.

"If we went anywhere in the world without a passport we wouldn't be let in," he comments.

A record number of migrants crossed the Channel in the first six months of the year

The BBC was given exclusive access to a service in Stoke-on-Trent that provides comprehensive support for asylum seekers arriving in the city.

About 300 people come through Asha's doors every week, needing food, clothes and advice.

Those they help describe living in terror of deportation, homelessness and poverty, even once granted asylum.

Hama fled Iraq nine years ago in the back of a lorry when the Islamic State took over the town where he lived.

Some of his female relatives were kidnapped, and both his parents were killed.

"My brother's body was never found so he is presumed dead," he says.

Hama fled Iraq in the back of a lorry nine years ago

The UK was not his intended destination - in fact, there wasn't one.

"You are in the control of the smugglers," he says, being told "that's not your problem" when he asked where they were heading after arriving in Germany.

"The lorry was 10-12 hours, I thought we were still around France or Belgium. But when the lorry driver opened the door, we were in Dover, in the UK."

Hama was homeless for six years. He slept rough in a park in Derby until he was granted refugee status.

'The Rwanda Bill won't work'

He volunteers at Asha now and offers Kurdish interpreting services to the city council, Red Cross and Staffordshire Police.

Since the Rwanda asylum plan was announced, one of his housemates has disappeared.

"I think he just ran away," he says. "I think asylum seekers will start to hide slowly, slowly."

But he says the Rwanda Bill would not have deterred him leaving Iraq.

"When you're looking for the safe country, it doesn't matter where you are going to be, what's going on in this country," he adds.

"Even now boats come around, people come around so I think Rwanda doesn't stop people."

Mohammed, not his real name, from north Africa, says he was desperate to find work in England. He has now finally secured a job after more than seven months of trying.

He became homeless after being granted refugee status.

"When you stop being an asylum seeker, you lose financial support," he explains.

Evicted from his accommodation, he says he applied for hundreds of jobs before getting an offer.

He tells the BBC he has been sleeping on friends' floors.

"Every morning I take everything I own and leave for the day," he explains, returning late at night for fear of causing problems for those helping him.

The charity says cases like Mohammed's have become the norm and claims funding promised by the Home Office to help those transitioning from asylum seeker to refugee status has not materialised.

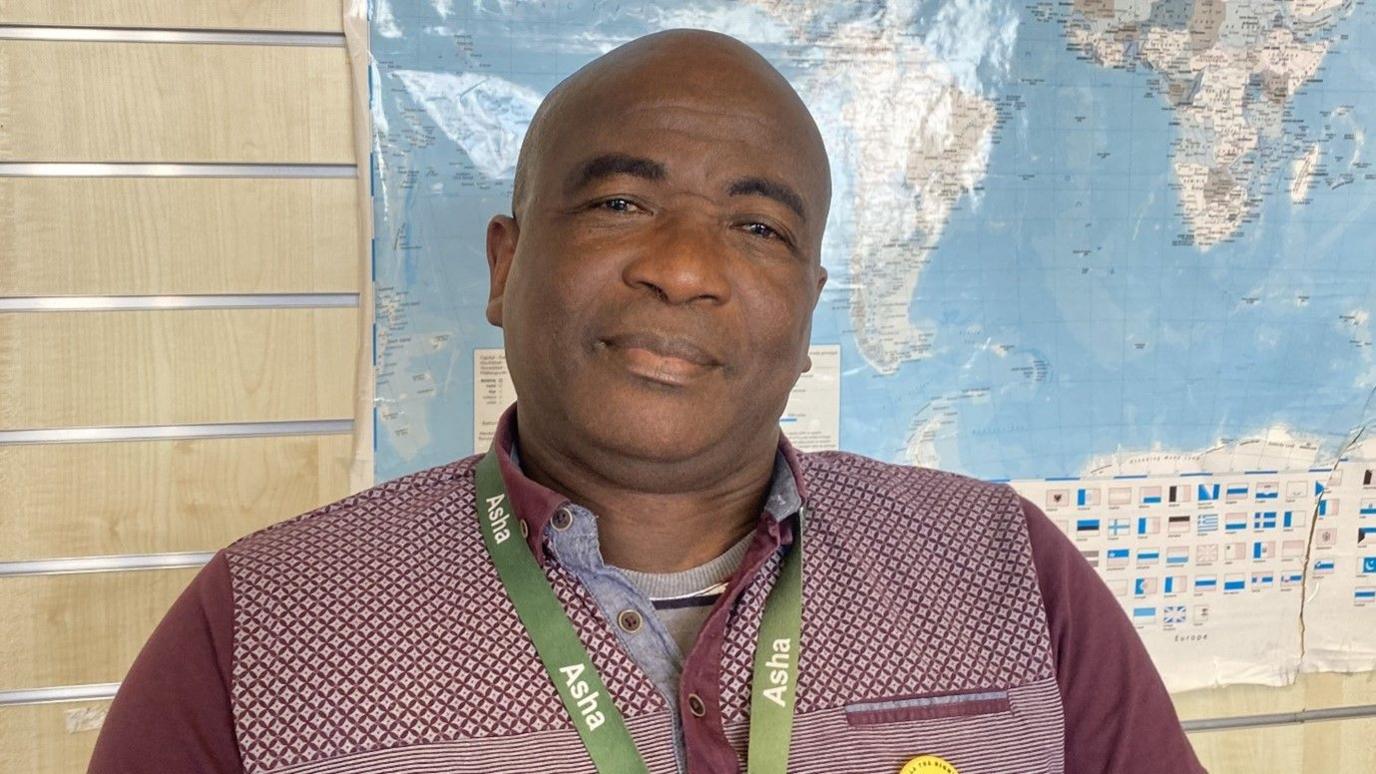

Tamba believes some immigrants will end up in modern slavery

"It takes a while to find jobs, the council are overstretched and unable to provide housing and many find that universal credit is not enough to buy food as well as pay rent," says co-ordinator Tamba Musa.

He fears some asylum seekers will leave their accommodation due to fear of deportation, which will leave them undocumented and at risk of exploitation.

He expects some will turn to crime to feed and house themselves or end up being drawn into modern slavery.

Rodica White, 49, moved to England from Romania after meeting her husband

Back in Stafford, Ken Edwards describes as "bunkum" the view "these people in the small boats are crippling the country and filling up the hospitals and the waiting lists".

He says immigrants in boats constitute "a fraction of the immigration that they're [the government] allowing in".

"While our own people won't do the caring jobs we've got to fetch people in to do it," he says.

"When we were in Europe [the EU] we had thousands of foreign workers doing them sort of jobs. We need them, it's simple as that."

Meanwhile, NHS mental health worker Rodica White, 49, thinks immigration is "a massive problem in England".

A British citizen who moved from Romania for work 20 years ago, she says: "I think immigration should be sorted by skills.

"I've got two jobs and that's why I have a bit of a better life, but if you don't work you don't get paid. You come here, you expect a job, a house, whatever... when I came here I didn't expect anything."

Aislinn Humphries feels there are more pressing problems than immigration affecting Stafford

Some people in Stafford want to talk about concerns that aren't immigration.

Nigel Bruce, who works at Screwfix after retiring from the military, is worried about house building around the town.

"You look to where is the infrastructure is going... A&E only open 12 hours a day," he says. "Things are stretched now, if you're ill out of that time you're either at Wolverhampton or off up to Stoke."

Barbara, a retiree who used to work in engineering, adds: "There's massive building of houses... which will eventually meet up with the smaller towns outlying and that's going to be more of a burden on services - doctors, dentists, schools."

Student Aislinn Humphries, 20, who was born and bred in Stafford, says: "I feel like there's more pressing problems [than immigration] with where investments have been going recently that have resulted in worse turnout for the town."

She had hoped for more money ploughed into the high street.

Dean Challinor, who is recovering from a stroke, gave up voting decades ago.

"I just think the country’s upside down, it’s gone backwards instead of forwards," he says.

"The industry's gone and all the people, what have they got? The young 'uns, they've got nothing, to be fair, today."

Dean Challinor says there are few prospects for young people now

A couple who live near Stoke-on-Trent tell the BBC the UK should be more welcoming to immigrants but that the current system needs "sorting out".

"If it was me in charge of the Home Office I would put a tag on people as they landed on shore, find out where they go, let them go and earn a living," the man tells us.

"And not keep them short of money, short of digs, and short of dignity. It's awful for these people. Some of them perhaps shouldn't be here and perhaps some of them we don’t want... we don't know that until we know who they are."

His wife adds: "They could be doctors or nurses and we need doctors and nurses - we're short of staff. If we got them working, the hospital waiting lists might go down a bit."

"We're a friendly country by nature," her husband says. "Let's keep it that way."

Additional reporting by Rebecca Woods and Susie Rack

Follow BBC Stoke & Staffordshire on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published10 January 2024

- Published26 January 2023