Will there be a drought where I live?

Many reservoirs in northern England, like Lindley Wood in Yorkshire, have hit extremely low levels

- Published

Millions of people across England and Wales are in regions hit by drought, and further areas are at risk of following if dry weather continues.

England's National Drought Group, led by the Environment Agency, says the water shortfall situation is now a "nationally significant incident".

Parts of eastern Scotland are also being closely monitored amid low water levels, according to the water companies there.

So how is your area doing and how close are you to a drought? Here's a look at what's happening around the country, including our rain, rivers and reservoirs.

What is a drought and is there a hosepipe ban in my region?

There is no single definition of drought, but it is ultimately caused by a prolonged period of low rainfall, which has knock-on effects for nature, agriculture and water supplies.

A decision to declare drought is taken based on an assessment of current water levels and long-term weather forecasts.

It is a public sign that water companies might introduce restrictions on water use, such as hosepipe bans, if they aren't already in place.

Areas with hosepipe ban areas don't exactly match drought declarations, because plans to manage water vary between regions.

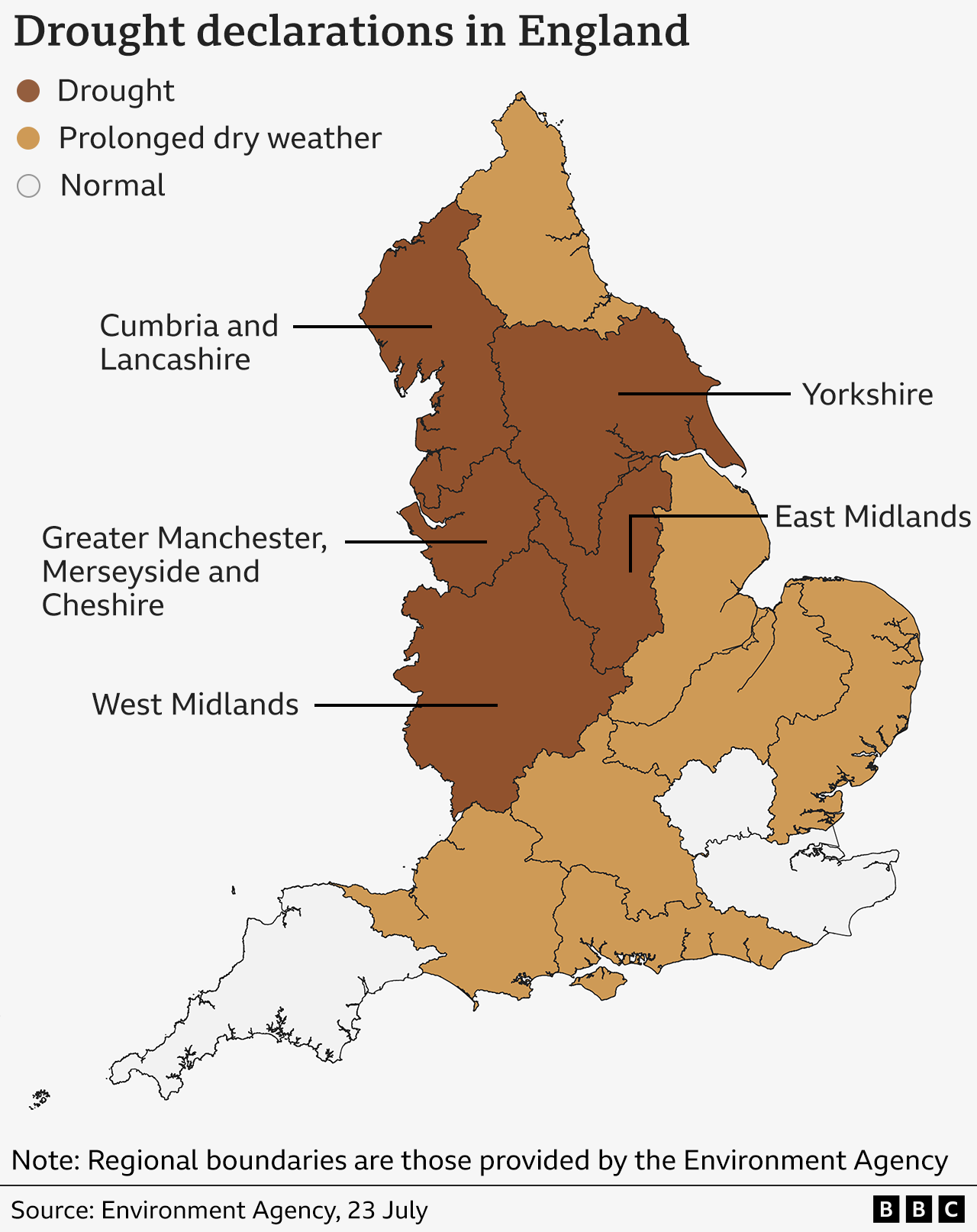

In England, the North West, Yorkshire, East Midlands and West Midlands are in drought, the Environment Agency says, as shown by the map below.

Most of the rest of the England is in a status of prolonged dry weather, the category below drought.

Southeast Wales is the only area outside England officially in drought.

The rest of Wales is in prolonged dry weather status, according to Natural Resources Wales, while there are no official droughts currently in Northern Ireland.

Scotland does not declare droughts but monitors "water scarcity". Parts of eastern Scotland are in "moderate" scarcity – the second most extreme category – which means there is "clear" environmental impact.

One of the driest springs on record

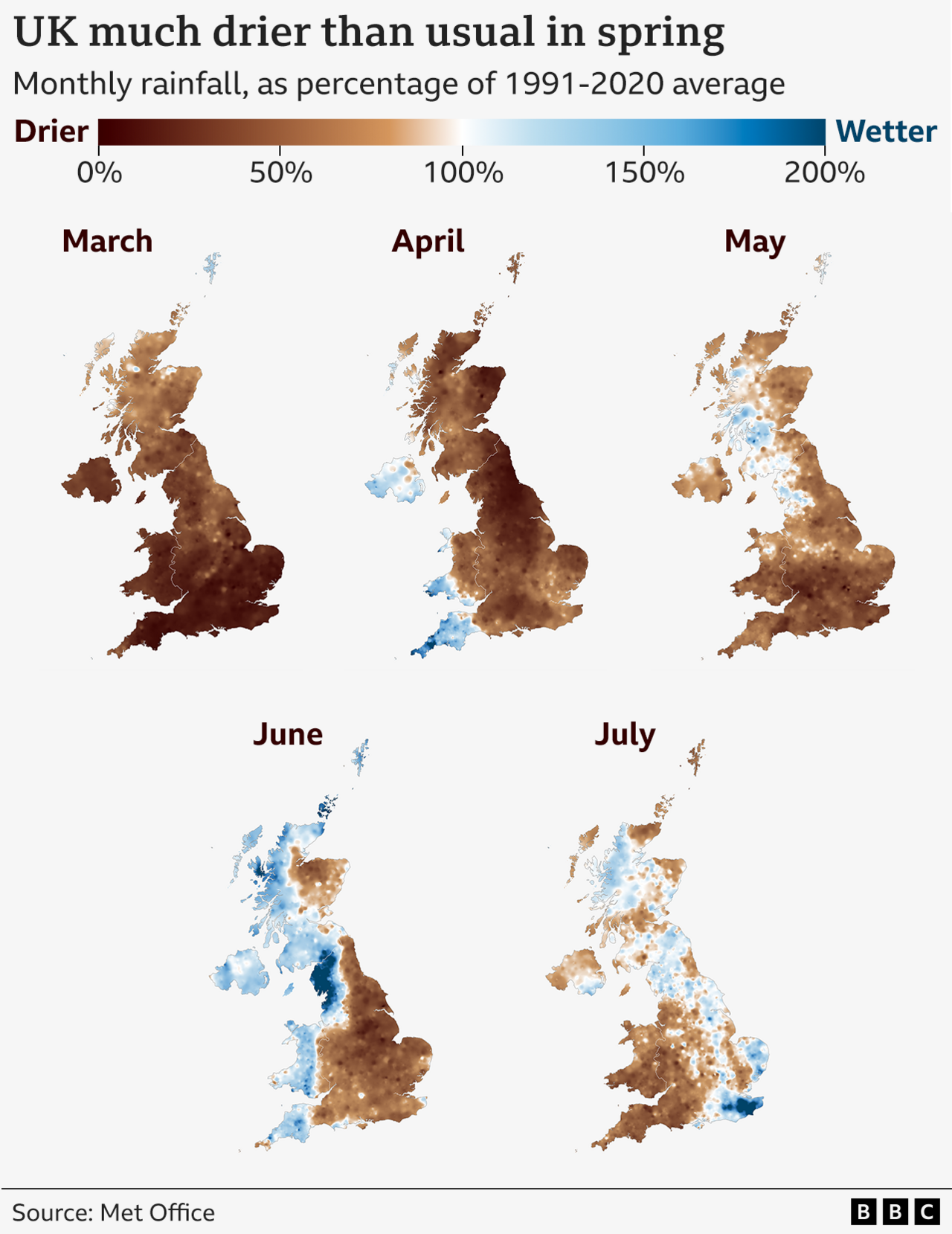

The main reason for these droughts being declared is the long period of low rainfall.

The UK had its sixth driest spring since records began in 1836.

So there has been less moisture to top up our rivers, reservoirs and rocks below the ground.

If that lack of rainfall continues for a long time, it can strain the water supplies that serve our homes and businesses.

The Met Office says this summer is set to be one of the warmest on record, with below average rainfall across the UK.

However, while central, southern and eastern parts of England and Wales have continued to experience dry weather, some north western areas, particularly in Scotland, have seen more rain since the dry spring.

September has a greater chance of wetter and windier conditions, according to the Met Office.

Drier rivers for parts of the UK

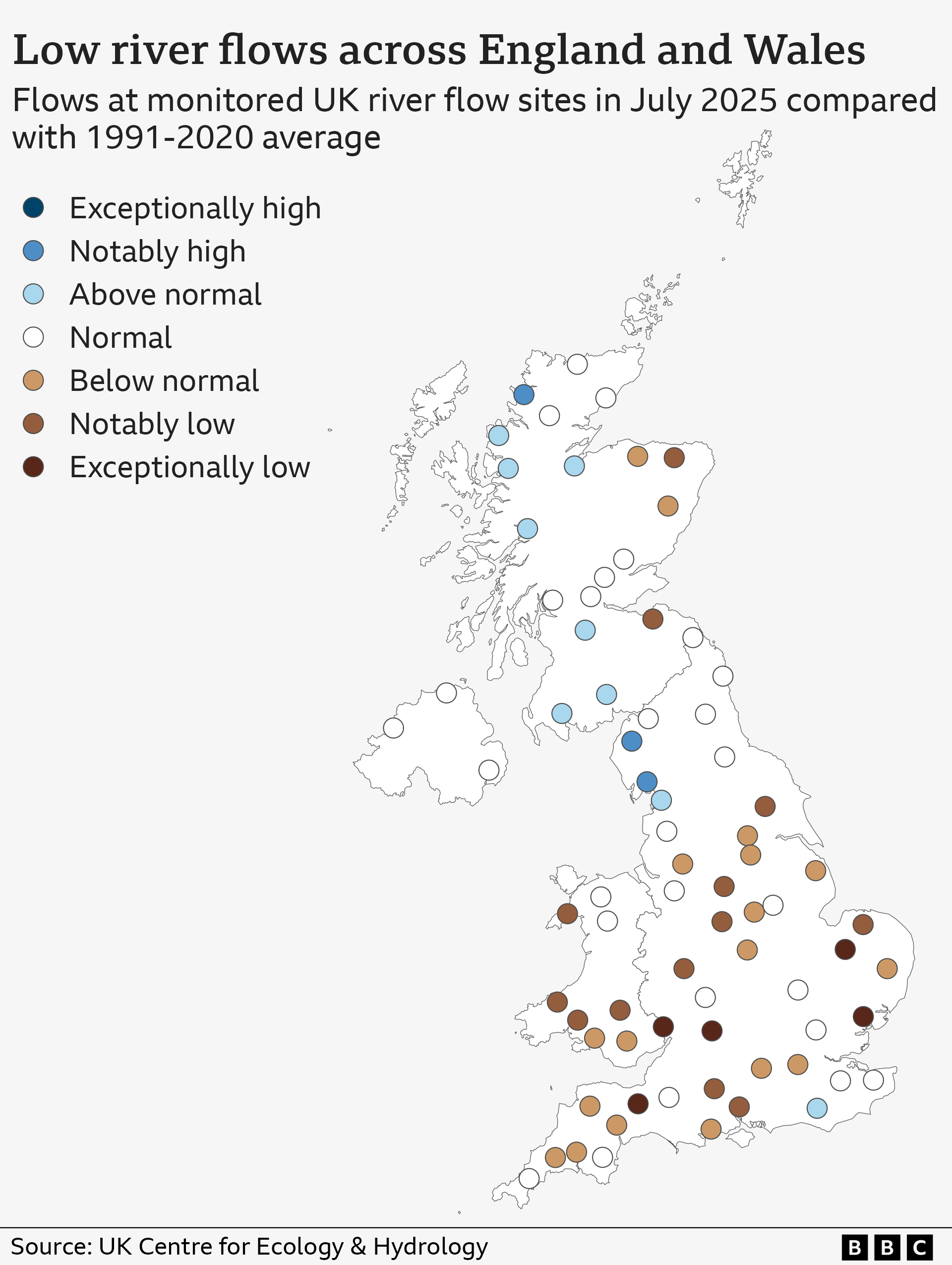

River flows across the UK showed a regional contrast in July.

In western Scotland, Northern Ireland, and northwest England, flows were generally normal or above average for the time of year.

However, many rivers in eastern, central, and southern England, as well as parts of Wales and eastern Scotland, recorded below normal or lower flows.

Some river flows in these drier regions are now comparable with, or even lower than, notable drought years such as 1976, 2011, 2018 and 2022, said Lucy Barker, hydrologist at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH).

Soil moisture levels have partially recovered after a very dry period, but some sites - particularly in the south of England - remain much drier than usual, UKCEH data shows.

Dry soils harm plant growth, hitting ecosystems and crop production. This dried out vegetation also brings a higher risk of wildfires.

Drier soils also warm up more quickly, which can amplify heatwaves.

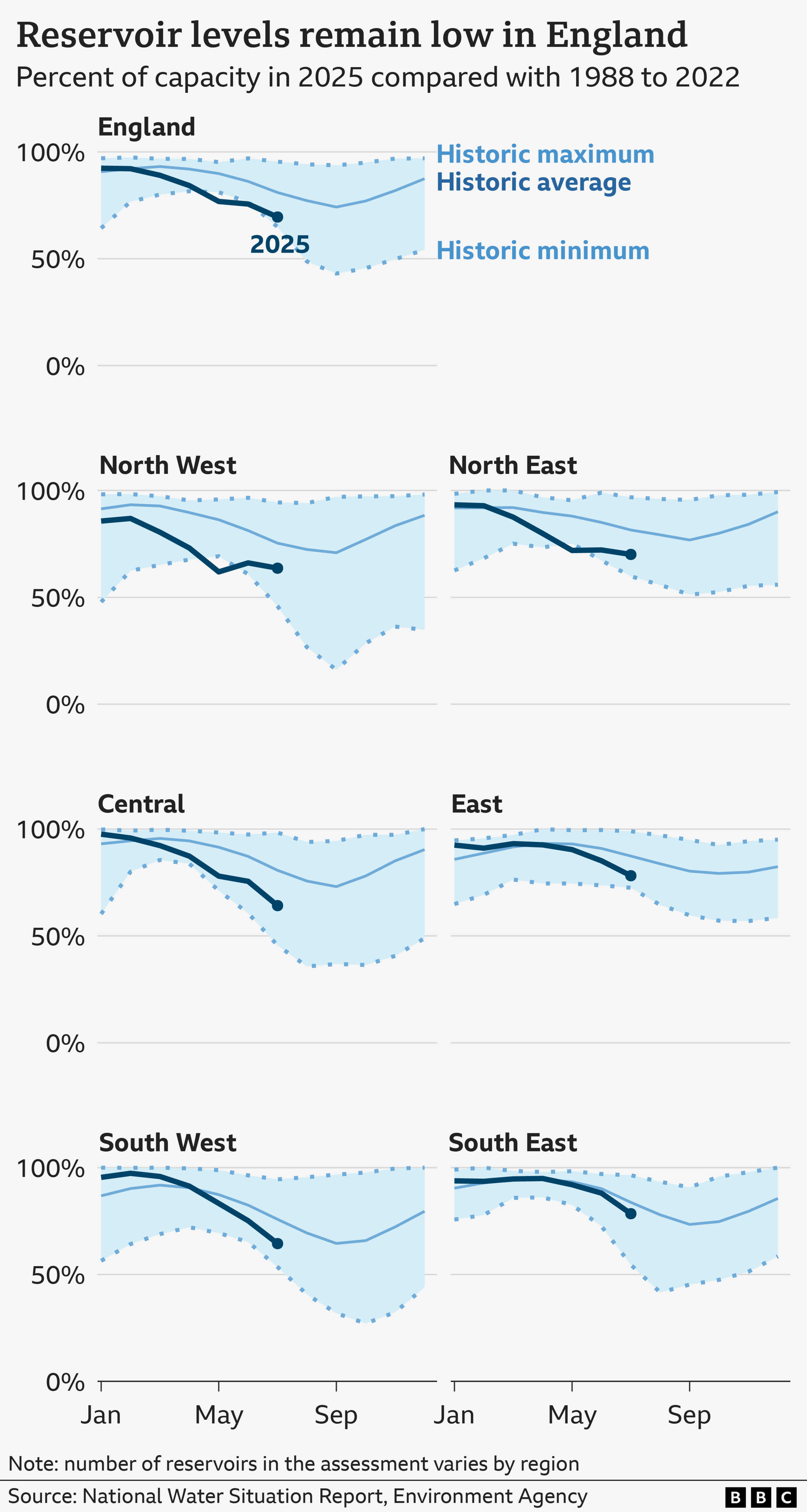

Low reservoirs across England

Reservoirs are a crucial part of water supplies in northern England, Scotland and Wales.

But England's reservoirs are at very low levels for the time of year in records going back more than 30 years.

Despite more variable weather last month, reservoir levels were below average in all English regions for the end of July.

The main reason for this is, of course, the lack of rain, but a small number of reservoirs can be affected by other factors.

Normally at this time of year, Scottish reservoirs are 82% full. They are currently at 73%, according to Scottish Water, with stocks in the east of Scotland running especially low.

In Wales, most reservoirs are around normal, Welsh Water said.

Reservoir levels in Northern Ireland are in a reasonable position for the time of year, according to NI Water.

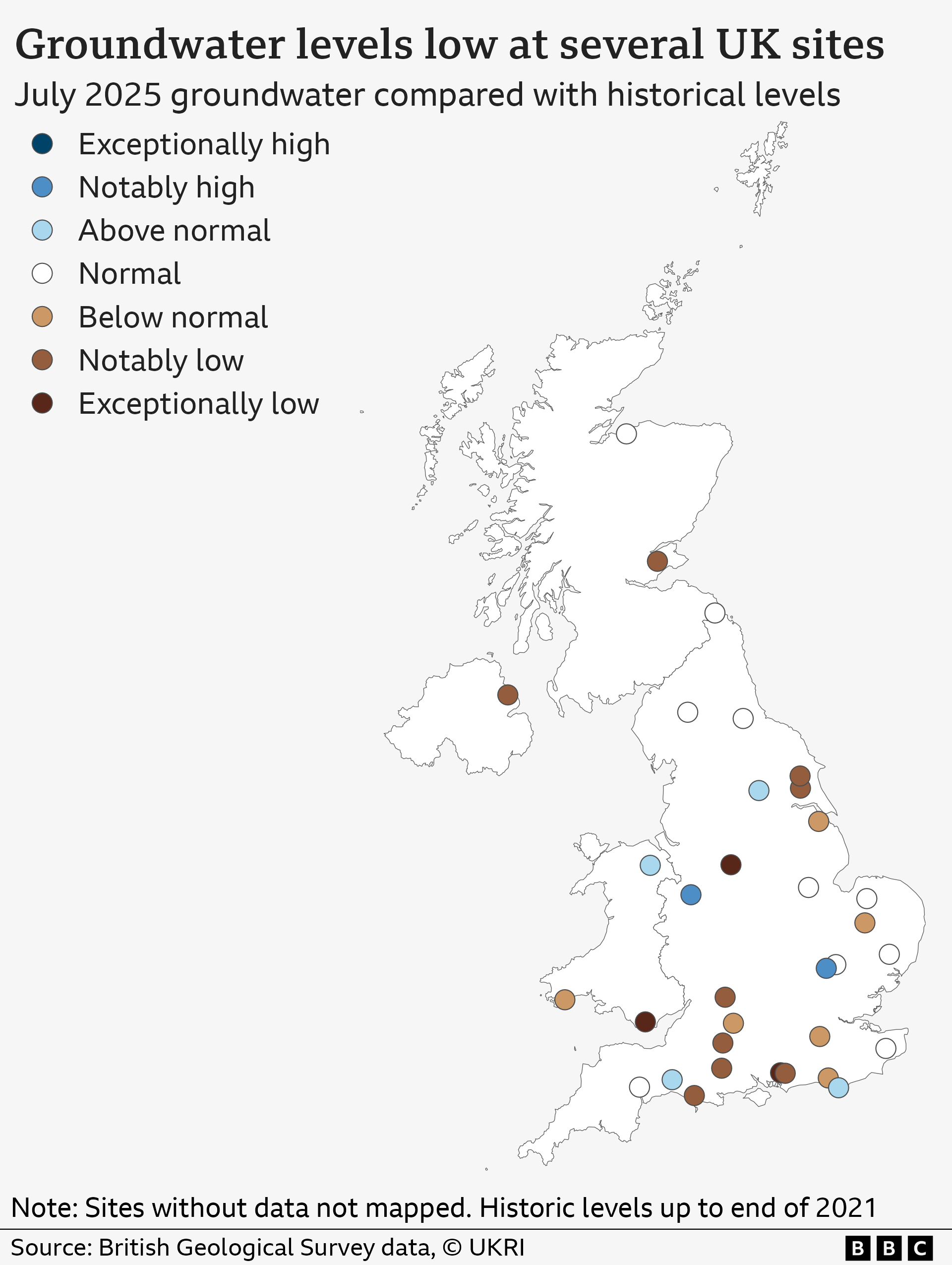

A more mixed picture underground

Much of south-east England relies more heavily on groundwater than reservoirs.

Groundwater originates as rainfall and is naturally stored beneath the surface in the pore spaces and fractures in rocks. Rocks that store lots of groundwater are called aquifers.

It accounts for a third of England's water supply, though this is much higher in the south and east.

That is down to the UK's varied geology, which affects how much water can be stored in the ground.

Water can flow more slowly through some rock types than others, sometimes taking years to respond to current conditions.

Some areas such as the South West and northeast Yorkshire are beginning to show declining groundwater levels due to dry weather in early spring, while conditions in places like East Anglia and London remain close to normal.

These groundwater stores "respond more slowly to changes in the climate than rivers, which is why they provide a useful buffer during periods of drought," said Prof Alan MacDonald of the British Geological Survey.

It is why groundwater droughts in the South generally take a longer time to develop but can be longer-lasting if they do occur.

What are the consequences of the dry weather?

People and nature are already feeling the effects.

Some farmers are facing the prospect of a second consecutive bad harvest after last year was affected by heavy rain.

Adapting to this year's dry weather is "hurting [farmers] financially and mentally," Rachel Hallos, vice-president of the National Farmers' Union, told BBC News.

With little rain, farmers have had to get water onto their crops using irrigation.

That has made things more expensive for them and means there is even less water to go around.

When the rain does come "it's going to be hitting hard ground and it's going to run off," she warns - "we could end up with a flood situation".

"Whatever else is going on, it is the weather that affects us the most," Mrs Hallos added.

"If this is the new normal, we have to be prepared."

And then there is the impact on wildlife.

A spokesman from the bird protection charity RSPB said that a big challenge has been making sure enough water is getting to key wetland habitats so that birds have safe places to nest.

"We need to be thinking about making our sites more resilient to climate change, as these periods of prolonged dry weather become the norm."

And it's not just water-loving birds that are having a hard time. Even in our gardens, common visitors like blackbirds can struggle to find worms and insects on our parched lawns, the RSPB says.

Is climate change to blame for drought?

Droughts are complex phenomena, driven by a mix of natural and human causes.

The Met Office expects the UK to experience drier summers on average in future as the world warms, though there has been no clear trend so far.

But rising temperatures can play a more fundamental role by sapping moisture from the soil via evaporation.

"A warmer atmosphere is thirstier for moisture and this can mean water in the soil, rivers and reservoirs are depleted more effectively, leading to more rapidly onsetting droughts, heatwaves and wildfires," said Richard Allan, professor of climate science at the University of Reading.

But there are other factors that determine whether dry conditions lead to water shortages, including how we use water.

As part of plans to address water shortages, the government is planning nine new reservoirs for England by 2050, in addition to one under construction at Havant Thicket in Hampshire.

But the Environment Agency has warned that measures to tackle water leaks and control water demand - potentially including hosepipe bans and more smart meters - may be needed in England too.

Water companies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland also said they were taking steps to secure future supplies.

Additional reporting by Dan Wainwright, Christine Jeavans, Muskeen Liddar and Elizabeth Dawson

Heatwaves: The New Normal?

How hot is too hot? From heat labs to firefighting helicopter pilots and wineries, this is a look at how extreme heat impacts people and environments in the UK.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.