Why would someone want to amputate healthy limbs?

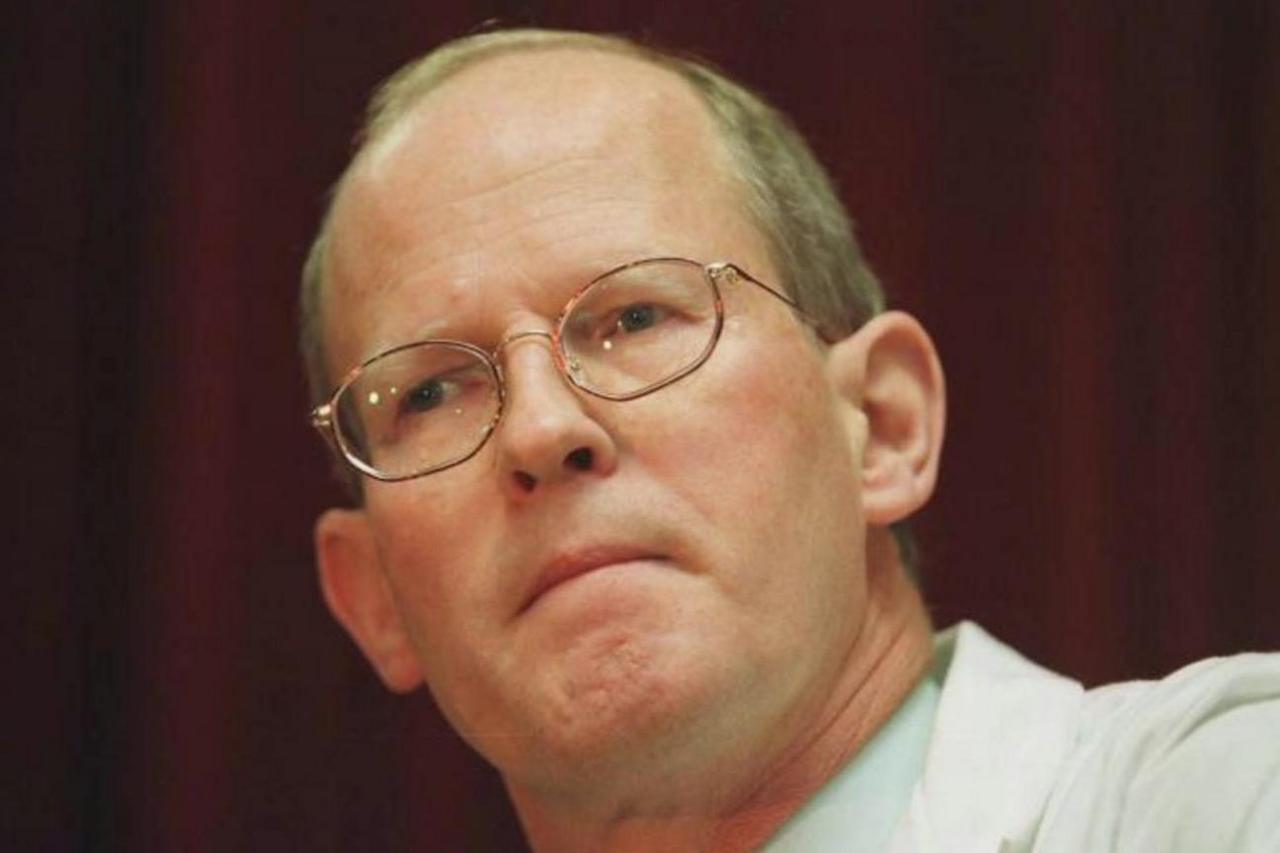

Neil Hopper told the world his legs were amputated after he got sepsis - but he was not telling the truth

- Published

One question has dominated conversations about the case of Neil Hopper, a surgeon who faked sepsis to have his own legs removed.

Why would a person want to have their healthy limbs amputated?

Hopper was jailed after pleading guilty to insurance fraud and possessing extreme pornography when it emerged that he had frozen his legs with dry ice so they would have to be removed in hospital.

Warning: Contains information some readers may find upsetting

The court heard Hopper, who grew up in Aberystwyth and Swansea and was living in Truro, Cornwall, had suffered body dysphoria since childhood and his feet were an "unwelcome extra" and a "persisting never-ending discomfort".

He also had a sexual interest in amputation and had paid to access videos of body mutilation.

Surgeon jailed after amputation of own legs

- Published4 September

When media began reporting on the case, 3,000 miles away in New York, psychiatrist Dr Michael First received a Google alert.

Dr First is a professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Columbia University, a research psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and was the man who got a condition known as body integrity dysphoria, external (BID) added to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), a globally recognised system maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO) that classifies diseases and health conditions.

Dr First said much of what he read about Hopper reminded him of his BID patients, although it was not made clear in court whether Hopper had received a diagnosis.

What was clear from the court case was Hopper had also submitted fraudulent insurance claims and purchased body mutilation videos that the judge said had a "level of harm" that was "exceptionally high".

Last week Hopper was jailed for two years and eight months for insurance fraud and possessing extreme pornography

Dr First's interest in the condition began back in 1997 after he received a phone call from the BBC's Horizon programme.

The programme was following the story of two men who would go on to have healthy limbs amputated by a surgeon in Falkirk, Scotland. The hospital trust would later ban amputations for psychological reasons.

At the time Dr First was working on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), a handbook used by healthcare professionals to classify and diagnose mental disorders, and the programme makers were looking for his advice on what mental health condition the men may have.

"When they called me up, I said 'I have never heard of this'," said Dr First.

"So the scientist in me immediately said, 'what is this new, unknown, unnamed condition?' And that's what got me started."

Through his early research he became aware of a condition called apotemnophilia - where someone is sexually aroused by the idea of being an amputee, and acrotomophilia - when someone has a strong sexual interest in amputees.

Then he got a phone call from a man looking for his help - the man wanted to have his healthy limbs amputated and hoped Dr First would be able to give him a diagnosis which would aid his case for surgical amputation.

"It turns out there's a whole community of people who wanted amputation and this guy was like the ringleader," said Dr First.

"He said he was interested in getting this condition added to the DSM and he wanted to know whether I'd be willing to help him."

Dr First said he could understand the man's logic.

"If you go to a surgeon and say 'I want my leg cut off', most surgeons would say 'get out of here, that's crazy' but if it was a condition in a medical manual you could argue they're treating a condition by doing the amputation."

'In the wrong body'

Dr First was intrigued and keen to understand more.

The man who had approached him was able to put him in touch with 52 others who either wanted healthy limbs amputated or to become paralysed.

After interviewing the individuals Dr First realised for many the main motivation was not sexual arousal but to "fulfil this sense that they're in the wrong body".

"The first time I heard it, I could not get my head around it. What is going on with these people?

"But they feel like they're an amputee in the body of a regular person.

"They're regular people, normal, married, kids, the works... except for this obsession."

He said they often lived with the secret, not even telling their spouse.

"I can understand somebody not wanting to tell anybody because you can imagine if somebody told you that you'd think they're completely crazy and people don't want that reaction," he said.

So what was Dr First able to ascertain from his research?

He said it was extremely common for these people to pretend they were an amputee by tying their limbs up or using a wheelchair.

"They get a lot of relief from that," he said.

He said in his experience the condition always began in childhood.

"Nobody gets this after age 13," he said.

"I think some people are born with it... but I think the people who develop it have to have the predisposition."

He said some he had spoken to had lived with it for as long as they could remember while others could pinpoint an incident that triggered it.

"Somebody told me this story that when he was in primary school a classmate of his became an amputee in a swimming accident, and came back to school after getting his amputation and became like the hero, the most popular kid and everybody's fascinated," he said.

"So this guy is seeing that and it was the point where he wanted to be an amputee, it sort of planted this in his head and it lasted the rest of his life."

Surgeon Robert Smith amputated healthy limbs from two patients in Falkirk, Scotland in 1997, before his hospital trust banned amputations for psychological reasons

Dr First said he had spoken to some who were desperate to have one leg amputated while others wanted both.

He said others wanted arms and fingers removed while some want to be paraplegic.

He said there was a case where somebody had wanted to be blind and blinded themselves with acid.

All who lived with the experience suffered huge mental anguish, he said.

"These people live in agony.

"Some are suicidal because it's intolerable, it's on their mind all the time."

Dr First was unable to collect enough data for BID to meet the threshold for it to be added to the DSM but was able to get it added to the International Classification of Diseases.

While he believes it be a psychiatric condition, he said other researchers regarded it as a neurological condition, external, where from birth the brain's body representation network is not correctly wired.

So what treatment options are there? Could these people benefit from psychological therapy or medication?

"A lot of these people are depressed about this so using antidepressants to treat the depression certainly would help them and the relief of suffering, but it does not take away the desire," he said.

He said although there had been some small success in treating people with antipsychotics - "although these people are not psychotic" - the only known treatment that had put an end to their mental anguish was amputation.

'Nobody knows'

But clearly that poses huge ethical concerns.

"It's scary," he said.

"If you do it and it turns out to be wrong you can't get the leg back.

"I don't know of any case of somebody who's had an amputation and then regretted it but the people who had it and regret are maybe not talking because they feel so bad about the fact they did it, so it's very distorted."

The condition is believed to be rare but Dr First said shame and secrecy around it meant many who lived with it did not speak out and it was therefore hard to put a figure on the number of people who have it.

"I know from other countries it exists everywhere," he said.

"For the majority of people who have it right now nobody knows about it, they haven't told anybody, they're suffering in silence."

If you have been affected by the issues raised in this story, BBC Action Line features a list of organisations which can provide support and advice.

Related topics

Related links

- Published19 August

- Published5 November 2018

- Published17 July 2023