'We lived a double life to hide my little boy's HIV'

Lee was "shunned" for having HIV

- Published

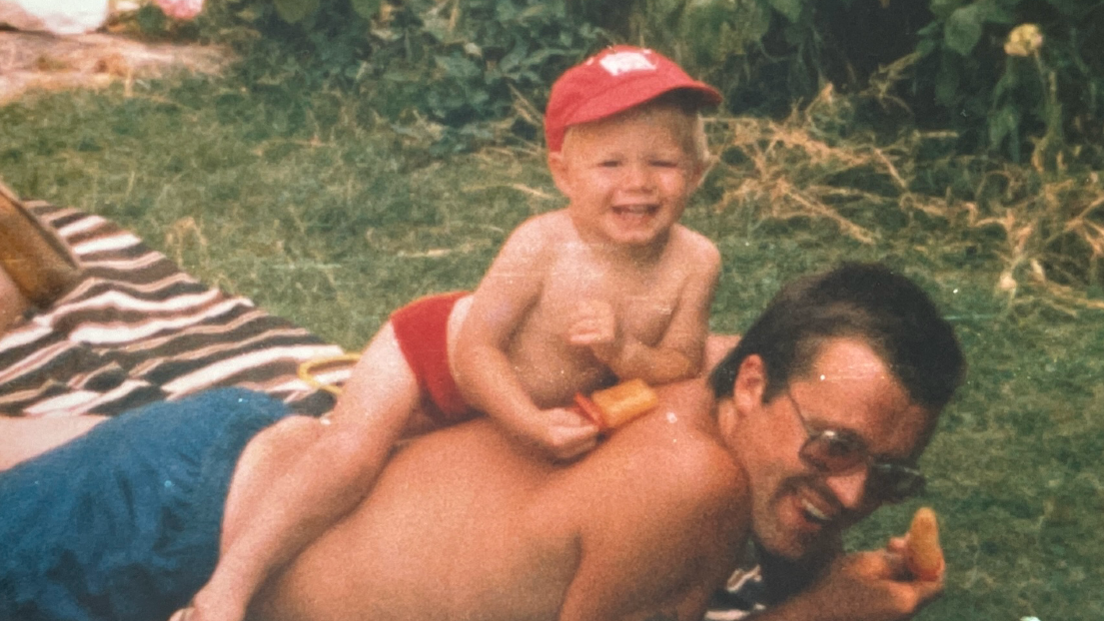

“We were living a double life, lying to everyone around us. We never told anybody about our little boy's HIV because we wanted him to have a normal life - he was just a child, like any other, but he was given a deadly infection.”

Lee was just two when he was infected with HIV in the infected blood scandal, which has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history.

But as his mum, Denise Turton, tried to cope with her son's diagnosis, she found herself an outcast in the local community in Nailsea, near Bristol.

“The other mums stood away from me at the school gates, some even told me he should be dead,” added Denise.

“Our little boy wasn’t invited to any birthday parties, I mean, how do you explain that to a child?"

Denise Turton said she became an outcast in her community after her son's diagnosis

In the early 1980s, the stigma surrounding HIV meant that within weeks of Lee's diagnosis, there were newspaper reporters at the school gates.

They knocked at the door of the family home and Denise and her son even had to escape through the back door on one occasion because they felt unsafe.

That was the moment when Denise and her husband Colin began to close themselves off from the rest of the world. They felt there was no one they could turn to for help.

“We shut ourselves away, lost all of our friends, and got on with our own little life in our own bubble," Denise said.

Denise and Colin shut themselves away and lost all their friends

As a six-month-old baby in November 1981, Lee was diagnosed with haemophilia, a rare genetic condition which meant his blood did not clot properly.

In the 1970s, a new treatment had been developed to replace the missing clotting agents, made from donated human blood plasma.

But whole batches of the replacement blood products were contaminated.

Lee was infected with two viruses when he was just two years old - HIV and hepatitis C.

“We had been asking for months how safe the treatment was. They kept saying it was fine,” said Denise.

“There was nothing to cure him. I knew that we were going to lose him.”

Lee was one of more than 30,000 people who contracted HIV and hepatitis C after being given contaminated blood products during the 1970s and 1980s.

A public inquiry into the treatment disaster will announce its findings in May after months of delays.

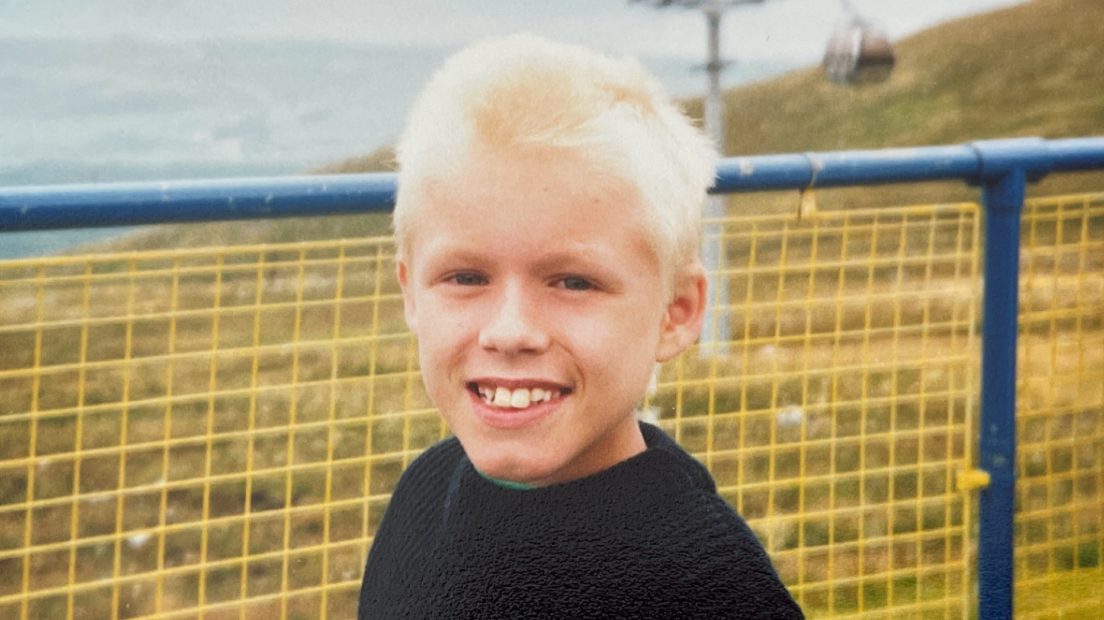

Lee was described as a "happy and cheeky" little boy

“We were very angry. We were given no information about the infection or how to manage it. No one ever said sorry, we were left alone," said Denise.

Being ostracised by their local community had destroyed Lee's chance to live a normal life. The family say they decided they had no choice but to move away and start again.

They went to Cornwall but even that meant living a “double life”.

“Lee was a normal, cheeky little boy. It was nice for him to go to a new school where people weren't looking at him funny or talking about him,” said Denise.

“But we couldn’t make any friends because we were having to keep a big secret.

“You go home and shut the door. You have two lives, a life outside where you lie, and the other in the house, where we talked about things.

"We couldn’t let people into that life. That was our private life.”

But Lee’s chance at a normal life lasted only a few years.

Lee died from AIDS after his haemophilia was treated with contaminated blood plasma

At age eight, he started picking up infections at school.

But those “little colds” were “big ones” for Lee.

His immune system was growing weaker and weaker as HIV was developing into Aids.

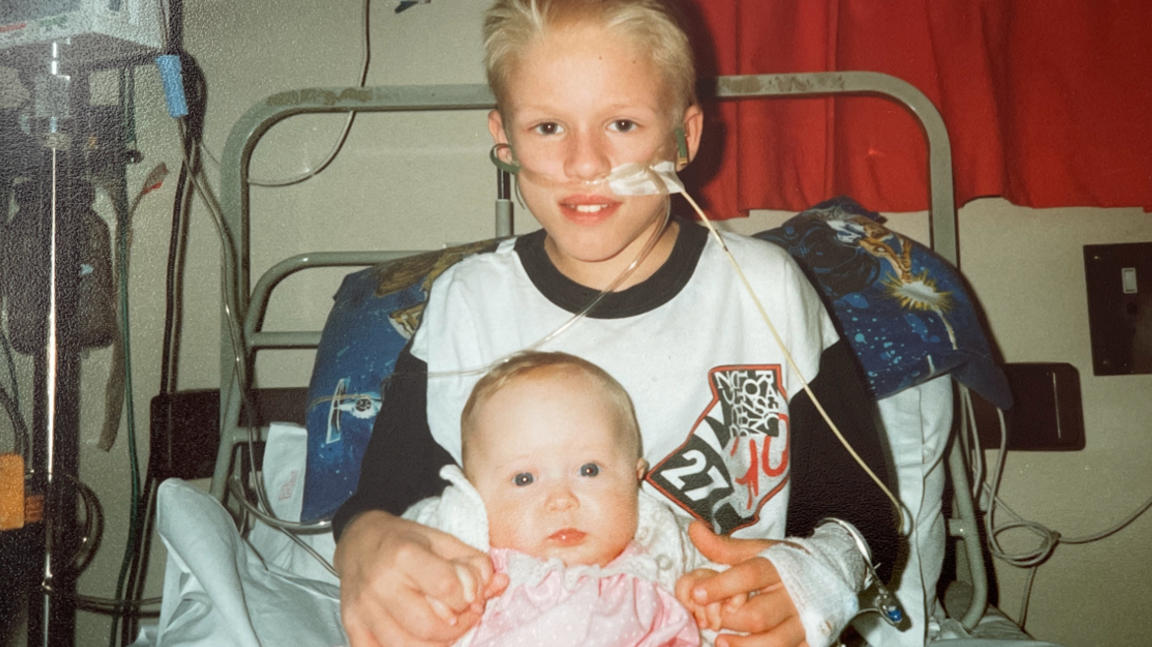

“He would spend weeks in hospital with illnesses. His body couldn’t fight it,” said Denise.

“He had night sweats, days where he couldn’t see, hear, or eat food.

"He lost all of his weight, he had no energy, he went straight to sleep after school each day because he was so tired.

“Our little boy was put through all of this because he was given a virus.”

Lee knew he was dying but was too ill to be angry about the reason why, Denise added.

Lee with his younger sister Kerrie

Lee had a seizure and was taken to hospital when the family had gone to visit relatives in Bristol.

“We were told he had up to 10 days to live,” Denise said.

“He wanted to come home, so we went back to Cornwall. We wrapped him up and took him to sit by the sea.

“He passed away on day eight.”

A public inquiry into the treatment disaster will soon announce its findings

Lee died on 22 January 1992, aged just 10.

More than 30 years later, Denise and Colin are hoping the infected blood inquiry will bring closure.

“We have been lied to for over 40 years, we just want justice for Lee," she said.

"He needs to be recognised, and for that to happen we need the truth in black and white.

“As well as losing our son, we have lost our own lives, we were made to be people we didn’t want to be, liars, who had no choice but to hide from the world."

A government spokesperson said: "This was an appalling tragedy, and our thoughts remain with all those impacted.

The spokesperson said they have consistently accepted the moral case for compensation.

"We will continue to listen carefully to those infected and affected about how we address this dreadful scandal," they added.

More on the infected blood scandal

- Published7 March 2024

- Published28 February 2024

- Published18 December 2023