Inside the century-old building standing above 400,000 gold bars

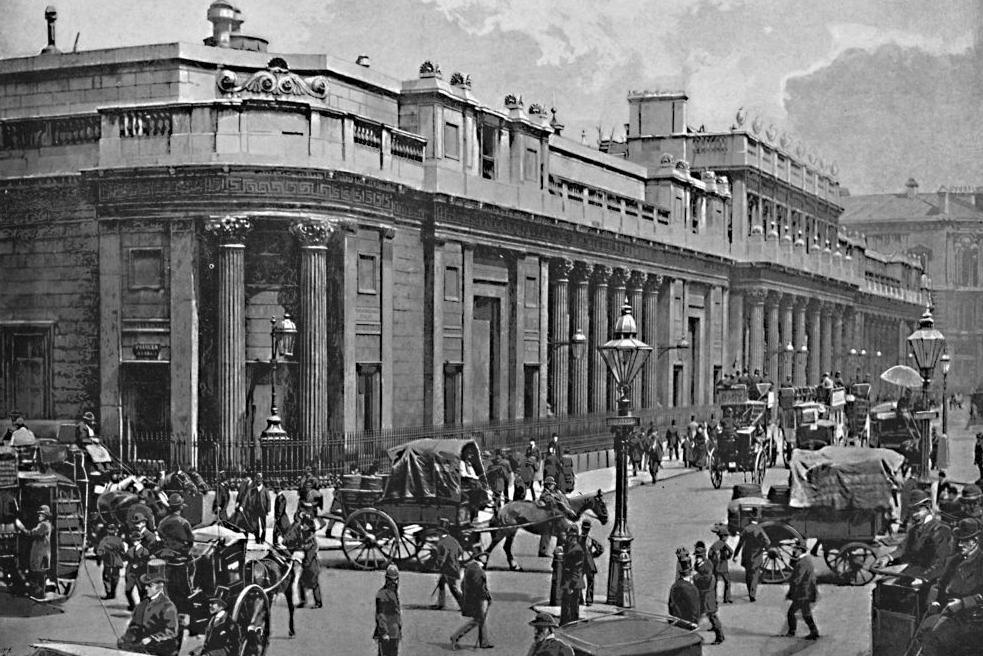

The Bank of England covers a three-and-a-half acre site in the City of London

- Published

The echoing boom of a slammed door rattles around the walls of the Bank of England's grand columned entrance.

Across the floor and walls sprawl grand mosaics and sculptures depicting lions, piles of gold, thunderbolts and ancient Roman gods.

"When this building was created, it was designed as a working bank building. There were people coming and going all day," explains the Bank of England Museum's curator, Jenni Adam.

"And immediately they were greeted with this sense of grandeur along with lots and lots of messages about what's happening in this site."

The parlours of the first floor have a very different atmosphere to the rooms on the floor below

One hundred years ago work began to rebuild the Bank of England - a place which had started as a townhouse in the 1700s and expanded over subsequent centuries.

To mark this centenary a new exhibition has begun in the bank's museum revealing more about what can be found inside one of Britain's most secure buildings.

Ahead of its opening the BBC was given a rare look inside the bank itself, where some of the country's key financial decisions are made and which houses some 400,000 bars of gold in its basement vaults.

Sir John Soane introduced the windowless wall in the 1800s which still surrounds the site

Attempts were made to reproduce the grand banking halls of Soane's bank in the redevelopment

The bank was first granted a Royal Charter in 1694 when it was "founded for the use and benefit of the public as a way to manage the national debt and maintain stable finances in Britain", says Ms Adam.

It proved to be a huge success and by 1734 had moved to its current position in Threadneedle Street, with the premises becoming grander and slowly swallowing up surrounding land to cover a three-and-a-half acre (14,000 sq m) site within a windowless wall.

Various renowned architects worked on the bank including Sir John Soane in the 1800s, with his building considered one the jewels of the City.

However, by the first decades of the 20th Century, Soane's magnificent work was no longer proving fit for purpose.

"By the First World War the staff at the bank had gone from about 1,200 in 1914 to around 4,000 by 1918 and it was clear that there was a real capacity problem," says Ms Adam.

"It was doing a colossal job of managing an expensive national debt among many different aspects so it was decided to demolish and rebuild."

The bank continued to operate on the site throughout the 14-year project to rebuild it

Despite efforts to retain much of its historic character, the 14-year project proved controversial with one architectural expert branding the demolition "the greatest architectural crime to befall London in the 20th Century".

Even so, upon its completion in 1939 the project led by chief architect Sir Herbert Baker had cost a total of £5m - the equivalent of nearly £285m today - with no expense spared in the creation of the country's central bank.

Evidence of such wealth can be seen throughout a development which rises seven floors high and three below.

On the ground floor, mosaics by acclaimed Russian artist Boris Anrep spread along a maze of domed grey and black corridors, with figures and sculptures covering the fixtures and fittings throughout.

A large mosaic featuring two lions protecting a column of gold stands in the centre of the entrance hall while depictions of the Roman god Mercury are everywhere

Golden lions - symbolising security - pop up across the space, from specially designed lighting to staircase bannisters, while even the door handles are miniature recreations of Mercury, the Roman deity of communication and finance.

"There's a real blend of modern and ancient. It gives you the sense that even though this building is relatively new, it's been here forever," explains Ms Adam.

"There's a long legacy, a long heritage. You can trust it, it's going to stick around."

There is also a sign of an even older legacy at the bottom of one long spiralling staircase, where a Roman mosaic that was discovered in the 1930s remains on display.

Roman mosaics and numerous other artefacts from the time were found during building work

With grand banking halls based on those from Soane's building hidden off the corridor, occasional echoing thuds and bangs are the main reminder of the working nature of the building.

This enterprise also carries on up another set of staircases but in a very different, almost regal atmosphere.

One space, the first floor anteroom, is lined with red and gold silk, with centuries-old paintings hanging on the walls and an elaborately decorative fireplace standing beside a huge floor-to-ceiling window.

Leading off it are a thick set of wooden double-doors that head into a plush pale blue octagonal room where a portrait of a past governor glares down upon a reproduction of a room created in the 1780s.

Without the microphones placed around a curving table and two TV screens, few would consider this somewhere where discussions are held each month that have ramifications for millions of people.

"This is where to the present day, the bank's monetary policy committee meets to make decisions about rates as part of the bank's remit to manage inflation.

"That's why you want the double doors to make sure that nobody is listening into these very important market sensitive conversations," Ms Adam explains.

The first floor ante room houses artworks telling the changing story of the bank

Decisions on the Bank of England's interest rate are made each month in the committee room

The feel of a grand old building spotted with hints of modernity continues around the floor, with many of the stone elements from the previous bank-like fireplaces and columns reused by Baker.

Through another set of double doors is the court room, where a branded lectern stands in front of an 18th Century fireplace beneath an elaborate green ceiling and walls lined with gold.

Silhouettes of monarchs from across the lifetime of the bank line the room, while gilded griffins protect piles of gold above the doorways.

A wind vane also swings mechanically on one wall recalling a time when London's port was almost on the bank's doorstep and was such a key element of the city's economy.

"There's just lots of the symbolism of money and finance throughout the space... and gild as far as the eye can see," adds the museum curator.

The court room is used for activities like large meetings and formal receptions

The need for tight security means that tours of the building are incredibly rare. The only sight of any of the gold are the two bars held within the museum that are owned by the bank itself.

It's why Ms Adam says she's so pleased to be able to put on an exhibition to "open up the architecture" and give people an idea of what's inside.

"I've been working in the bank for 15 years and when you come in here every day, it becomes normal," she says.

"However, every so often you do go around and think 'this is so spectacular' - and there's just so many stories and details to share."

The yellow dining room on the first floor is still used by directors and governors for meals

Building the Bank will run at the Bank of England Museum until Spring 2027 and is free to visit

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

Stories from inside other London landmarks

- Published7 March 2024

- Published23 November 2024

- Published29 September 2023