Sudan's years of war - BBC smuggles in phones to reveal hunger and fear

Mostafa, Hafiza and Manahel film as their home, el-Fasher, comes under attack

- Published

"She left no last words. She was dead when she was carried away," says Hafiza quietly, as she describes how her mother was killed in a city under siege in Darfur, during Sudan's civil war, which began exactly two years ago.

The 21-year-old recorded how her family's life was turned upside down by her mother's death, on one of several phones the BBC World Service managed to get to people trapped in the crossfire in el-Fasher.

Under constant bombardment, el-Fasher has been largely cut off from the outside world for a year, making it impossible for journalists to enter the city. For safety reasons, we are only using the first names of people who wanted to film their lives and share their stories on the BBC phones.

Hafiza describes how she suddenly found herself responsible for her five-year-old brother and two teenage sisters.

Their father had died before the start of the war, which has pitted the army against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and caused the world's biggest humanitarian crisis.

Hafiza and her brother lost their mother in August 2024 when a shell hit the market where she was working

The two rivals had been allies - coming to power together in a coup - but fell out over an internationally backed plan to move towards civilian rule.

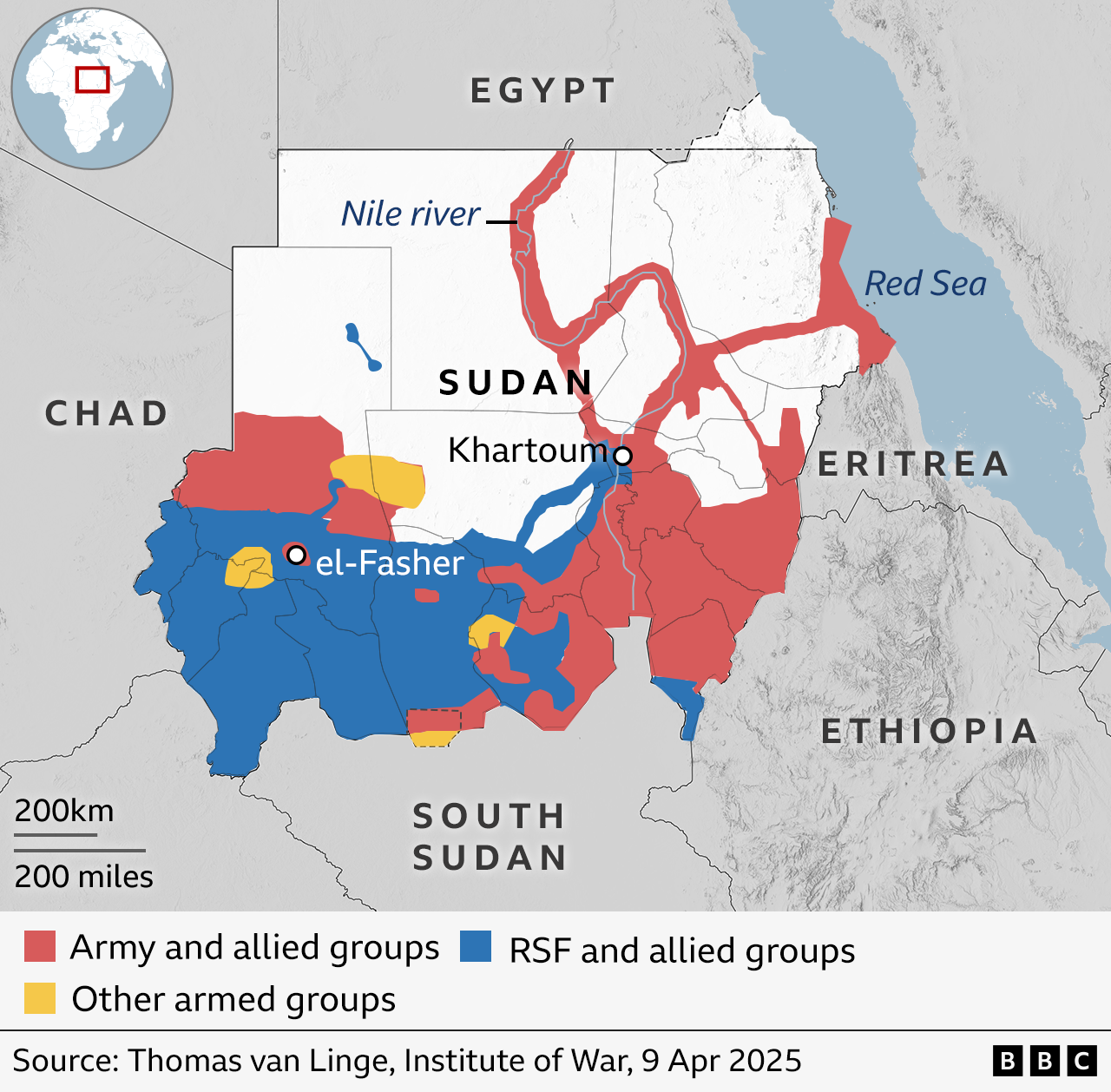

Hafiza's home is the last major city controlled by the military in Sudan's western region of Darfur, and has been under siege by the RSF for the past 12 months.

In August 2024, a shell hit the market where her mother had gone to sell household goods.

"Grief is very difficult, I still can't bring myself to visit her workplace," says Hafiza in one of her first video messages after receiving her phone, shortly after her mother's death.

"I spend my time crying alone at home."

Both sides in the war have been accused of war crimes and deliberately targeting civilians - which they deny. The RSF has also previously denied accusations from the US and human rights groups that it has committed a genocide against non-Arab groups in other parts of Darfur after it seized control of those areas.

The RSF controls passage in and out the city and sometimes allows civilians to leave, so Hafiza managed to send her siblings to stay with family in a neutral area.

But she stayed to try to earn money to support them.

In her messages, she describes her days distributing blankets and water to displaced people living in shelters, helping at a community kitchen and supporting a breast cancer awareness group in return for a little money to help her survive.

Her nights are spent alone.

"I remember the places where my mother and siblings used to sit, I feel broken," she adds.

Hafiza has tried to help displaced people in el-Fasher through voluntary work, including distributing blankets and food

In almost every video 32-year-old Mostafa sent us, the sound of shelling and gunfire can be heard in the background.

"We endure relentless artillery shelling, both day and night, by the RSF," he says.

One day, after visiting family, he returned to find his house near the city centre had been hit by shells - the roof and walls were damaged - and looters had ransacked what was left.

"Everything was turned upside down. Most houses in our neighbourhood have been looted," he says, blaming the RSF.

While Mostafa was volunteering at a shelter for displaced people, the area came under intense attack. He kept his camera rolling as he hid, flinching at each explosion.

"There is no safe place in el-Fasher," he says. "Even refugee camps are being bombed with artillery shells.

"Death can strike anyone, anytime, without warning… by a bullet, shelling, hunger or thirst."

Mostafa's house was hit by a shell and looted

In another message, he talks about the lack of clean water, describing how people drink from sources contaminated with sewage.

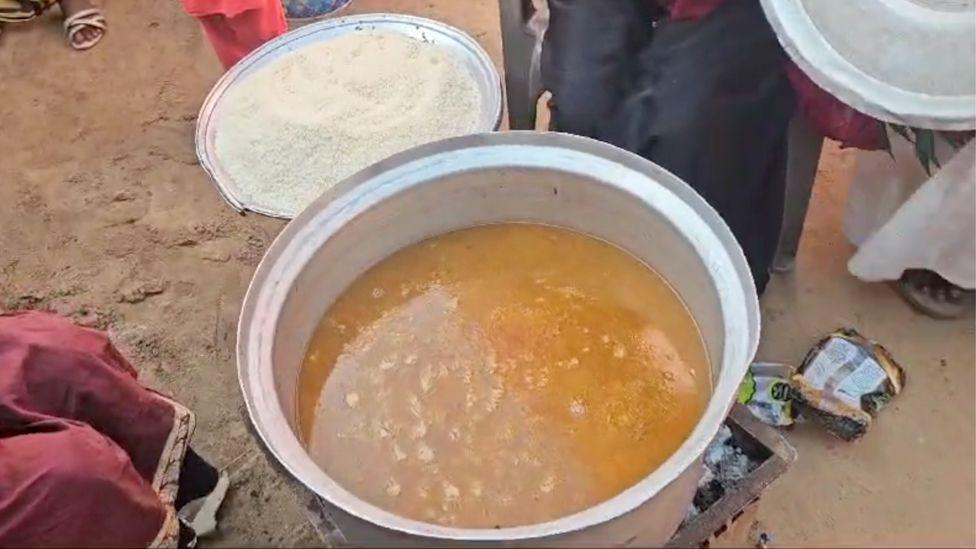

Both Mostafa and 26-year-old Manahel, who also received a BBC phone, volunteered at community kitchens funded by donations from Sudanese people living elsewhere.

The UN has warned of famine in the city, something that has already happened at the nearby Zamzam camp, which is home to more than 500,000 displaced people.

Many people cannot get to the market "and if they go, they find high prices", explains Manahel.

"Every family is equal now - there is no rich or poor. People can't afford the basic necessities like food."

The meals that Manahel helps to prepare are often the only food people can get

After cooking meals such as rice and stew, they deliver the food to people in shelters. For many, it is the only meal they will have for the day.

When the war started, Manahel had just finished university, where she studied Sharia and law.

As the fighting reached el-Fasher, she moved with her mother and six siblings to a safer area, further away from the front line.

"You lose your home, everything you own and find yourself in a new place with nothing," she says.

But her father refused to leave their house. Some neighbours had entrusted him with their belongings, and he decided to stay to protect them - a decision that cost him his life.

She says he was killed by RSF artillery in September 2024.

Manahel and her family had to move to another house because their home was close to the front line

Since the siege began a year ago, almost 2,000 people have been killed or injured in el-Fasher, according to the UN.

After sunset, people rarely leave their homes. The lack of electricity can make night-time frightening for many of el-Fasher's one million residents.

People with solar power or batteries are scared to turn lights on because they "could be detected by drones", explains Manahel.

There were times we could not reach her or the others for several days because they had no internet access.

But above all these worries, there is one particular fear that both Manahel and Hafiza share if the city falls to the RSF.

"As a girl, I might get raped," Hafiza says in one of her messages.

She, Manahel and Mostafa are all from non-Arabic communities and their fear stems from what happened in other cities that the RSF has taken, most notably el-Geneina, 250 miles (400km) west of el-Fasher.

Inside Darfur: Siege and massacres

With unprecedented access inside Darfur, BBC World Service shares rare accounts of life in el-Fasher and investigates allegations of atrocities in Sudan’s civil war.

People outside the UK can watch the documentary on YouTube, external.

In 2023 it witnessed horrific massacres, along ethnic lines, which the US and others say amounted to genocide. RSF fighters and allied Arab militia allegedly targeted people from non-Arab ethnic groups, such as the Massalit - which the RSF has previously denied.

A Massalit woman I met in a refugee camp over the border in Chad described how she was gang-raped by RSF fighters and was unable to walk for nearly two weeks, while the UN has said girls as young as 14 were raped.

One man told me how he witnessed a massacre by RSF forces - he escaped after he was injured and left for dead.

The UN estimates that between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed in el-Geneina alone in 2023. And now more than a quarter of a million people from the city - half its former population - are among those living in refugee camps in Chad.

We put these accusations to the RSF but it did not respond. However, in the past it has denied any involvement in ethnic cleansing in Darfur, saying the perpetrators had worn RSF clothing to shift the blame to them.

Few reporters have had access to el-Geneina since then, but after months of negotiation with the city's civil authorities, a BBC team was allowed to visit in December 2024.

Armed RSF units patrol the streets of el-Geneina

We were assigned minders from the governor's office and were only allowed to see what they wanted to show us.

It was immediately clear that the RSF was in control. I saw their fighters patrolling the streets in armed vehicles and had a brief conversation with some of them, when they showed me their anti-vehicle rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launcher.

It did not take long to realise how differently they viewed the conflict. Their commander insisted there were no civilians like Hafiza, Mostafa and Manahel living in el-Fasher.

"The person who stays in a war zone is participating in the war, there are no civilians, they are all from the army," he said.

He claimed el-Geneina was now peaceful and that most of its residents - "around 90%" - had come back. "Homes that were previously empty are now occupied again."

But hundreds of thousands of the city's residents are still living as refugees in Chad, and I saw many deserted and destroyed neighbourhoods as we drove around.

Our minders took us to a market in el-Geneina where shoppers said food prices had shot up

With the minders watching us, it was hard to get a true picture of life in el-Geneina. They took us to a bustling vegetable market, where I asked people about their lives.

Each time I asked someone a question, I noticed them glance at the minder over my shoulder before answering that everything was "fine", apart from a few comments about high prices.

However, my minder would often whisper in my ear afterwards, saying people were exaggerating about the prices.

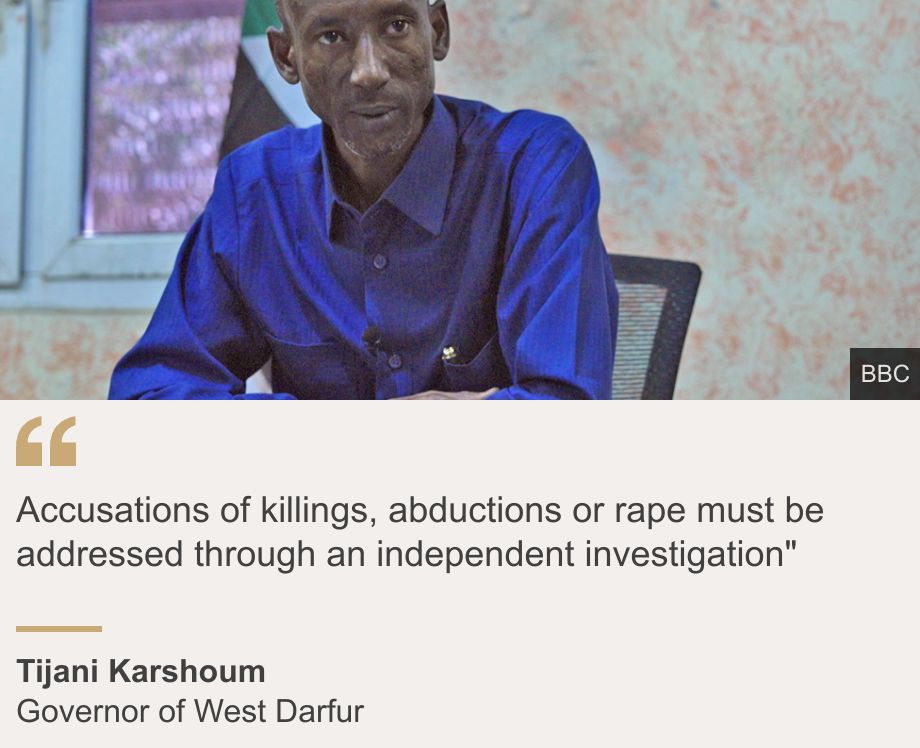

We ended our trip with an interview with Tijani Karshoum, the governor of West Darfur whose predecessor was killed in May 2023 after accusing the RSF of committing genocide.

It was his first interview since 2023, and he maintained he was a neutral civilian during the el-Geneina unrest and did not side with anyone.

Accusations of killings, abductions or rape must be addressed through an independent investigation"

"We have turned a new page with the slogan of peace, coexistence, moving beyond the bitterness of the past," he said, adding that the UN's casualty figures were "exaggerated".

Also in the room was a man who we understood to be a representative of the RSF.

Karshoum's answers to nearly all my questions were almost identical, whether I was asking about accusations of ethnic cleansing or about what happened to the former governor, Khamis Abakar.

Nearly two weeks after I spoke to Karshoum, the European Union imposed sanctions on him, saying he "holds responsibility in the fatal attack" on his predecessor and that he had "been involved in planning, directing or committing… serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law, including killings, rape and other serious forms of sexual and gender-based violence, and abduction".

I followed up with him to get his response to these accusations, and he said: "Since I am a suspect in this matter, I believe any statement from me would lack credibility."

But he stated that he "was never part of the tribal conflict and remained at home during the clashes" and added that he was not involved in any violations of humanitarian law.

"Accusations of killings, abductions, or rape must be addressed through an independent investigation" with which he would co-operate, Karshoum said.

"From the start of the conflict in Khartoum, we pushed for peace and proposed well-known initiatives to prevent violence in our socially fragile state," he added.

Mostafa decided it was too dangerous to stay in el-Fasher and left in November

Given the stark contrast between the narrative promoted by those in control of el-Geneina and the countless stories I heard from refugees across the border, it is hard to imagine people ever returning home.

The same goes for 12 million other Sudanese people who have fled their homes and are either refugees abroad or living in camps inside Sudan.

In the end, Hafiza, Mostafa and Manahel found life in el-Fasher unbearable and in November 2024 all three left the city to stay in nearby towns.

With the military regaining control of the capital, Khartoum, in March, Darfur remains the last major region where the paramilitaries are still largely in control - and that has turned el-Fasher into an even more intense battlefield.

"El-Fasher has become scary," Manahel said as she packed her belongings.

"We are leaving without knowing our fate. Will we ever return to el-Fasher? When will this war end? We don't know what will happen."

Additional reporting by Abdelrahman Abu Taleb.

More about the conflict in Sudan

Famine looms in Sudan as civil war survivors tell of killings and rapes

- Published20 March 2024

'Death is everywhere': Sudan camp residents shelter from attacks

- Published14 April

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external