A simple guide to what is happening in Sudan

- Published

Sudan plunged into a civil war in April 2023 after a vicious struggle for power broke out between its army and a powerful paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

It has led to a famine and claims of a genocide in the western Darfur region - with fears for the residents of city of el-Fasher after it was recently captured by the RSF.

More than 150,000 people have died in the conflict across the country, and about 12 million have fled their homes in what the United Nations has called the world's largest humanitarian crisis.

Here is what you need to know.

Why is there a civil war?

It is the latest episode in bouts of tension that followed the 2019 ousting of long-serving President Omar al-Bashir, who came to power in a coup in 1989.

There were huge street protests calling for an end to his near-three decade rule and the army mounted a coup to get rid of him.

But civilians continued to campaign for the introduction of democracy.

A joint military-civilian government was then established but that was overthrown in another coup in October 2021.

The coup was staged by the two men at the centre of the current conflict:

Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of the armed forces and in effect the country's president

And his deputy, RSF leader Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as "Hemedti".

But then Gen Burhan and Gen Dagalo disagreed on the direction the country was going in and the proposed move towards civilian rule.

The main sticking points were plans to incorporate the 100,000-strong RSF into the army, and who would then lead the new force.

The suspicions were that both generals wanted to hang on to their positions of power, unwilling to lose wealth and influence.

Shooting between the two sides began on 15 April 2023 following days of tension as members of the RSF were redeployed around the country in a move that the army saw as a threat.

It is disputed who fired the first shot but the fighting swiftly escalated, with the RSF seizing much of Khartoum until the army regained control of it almost two years later in March 2025.

Who are the RSF fighters?

The RSF was allied with the military until they fell out

The RSF was formed in 2013 and has its origins in the notorious Janjaweed militia that brutally fought rebels in Darfur, where they were accused of genocide and ethnic cleansing against the region's black African, non-Arab population.

Since then, Gen Dagalo has built a powerful force that has intervened in conflicts in Yemen and Libya.

He also controls some of Sudan's gold mines, and allegedly smuggles the metal to the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The army accuses the UAE of backing the RSF, and carrying out drone strikes in Sudan. The oil-rich Gulf state denies the allegation.

The army also accuses eastern Libyan strongman Gen Khalifa Haftar of supporting the RSF by helping it to smuggle weapons into Sudan, and sending fighters to bolster the RSF.

In early June 2025, the RSF achieved a major victory when it took control of territory along Sudan's border with Libya and Egypt.

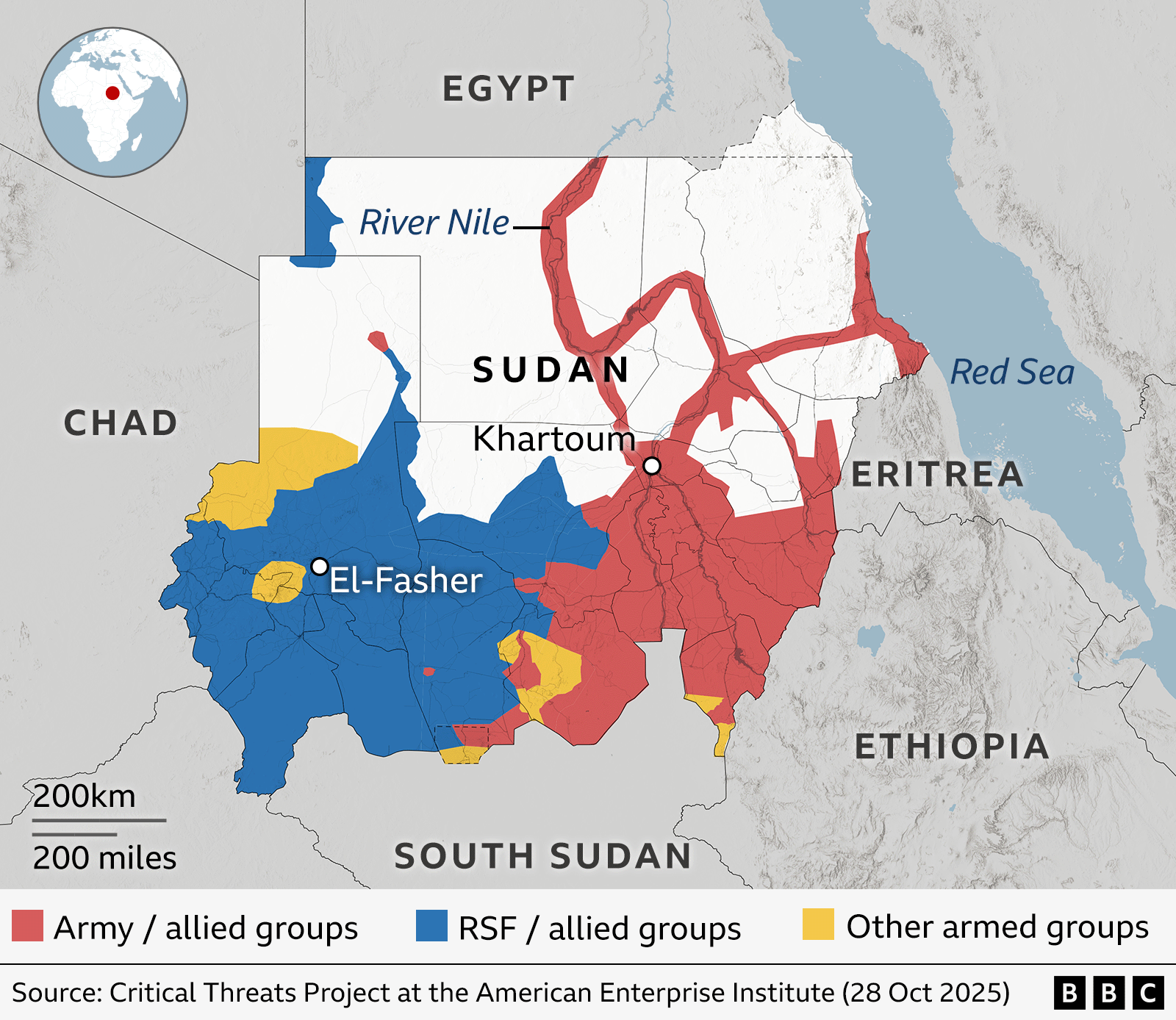

This was followed by the capture of el-Fasher in late October, meaning it controls almost all of Darfur and much of neighbouring Kordofan.

With the RSF's recent formation of a rival government, it is likely Sudan will split for a second time - South Sudan seceded in 2011, taking with it most of the country's oil fields.

What does the army control?

The military controls most of the north and the east. Its main backer is said to be Egypt, whose fortunes are intertwined with those of Sudan because they share a border and the waters of the River Nile.

Gen Burhan has turned Port Sudan - which is on the Red Sea - into his headquarters, and that of his UN-recognised government.

However, the city is not safe - the RSF launched a devastating drone strike there in March.

This was retaliation after the RSF suffered one of its biggest setbacks, when it lost control of Khartoum - including the Republican Palace - to the army in March.

"Khartoum is free, it's done," Gen Burhan declared, as he triumphantly returned to the city, though not permanently.

The city was a burnt-out shell by the time the RSF left, with government ministries, banks and towering office blocks stand blackened and burned. Hospitals and clinics were destroyed, hit by air strikes and artillery fire, sometimes with patients still inside.

The international airport - which was a graveyard of smashed planes - re-opened in mid-October to domestic flights, though its official opening was delayed by a day because a RSF drone hit an area nearby.

The army has also managed to win back near total control of the crucial state of Gezira. Losing it to the RSF in late 2023 had been a huge blow, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee its main city of Wad Madani, which had become a refuge for those who had escaped conflict in other parts of the country.

But el-Fasher, which was the last major urban centre in Darfur held by the army and its allies, fell to the RSF at the end of October.

Over 18 months, the RSF laid siege to the city, causing hundreds of casualties, overwhelming hospitals and blocking food supplies.

It recently stepped up it efforts by building an earthen wall around the city to trap residents and stop food from reaching people - and destroyed the nearby Zamzam displacement camp which had already been hit by famine.

Is there a genocide?

Many Darfuris believe the RSF and allied militias have waged a war aimed at transforming the ethnically mixed region into an Arab-dominated area.

In March 2024, the UN children's agency, Unicef, gave harrowing accounts of armed men raping and sexually assaulting children as young as one.

Some children have tried to end their own lives as a result.

In the same month, campaign group Human Rights Watch (HRW) said it was possible that the RSF and allied militias were carrying out a genocide, external in Darfur against the Massalit people and other non-Arab communities.

Thousands had been killed in el-Geneina city in a campaign of ethnic cleansing with the "apparent objective of at least having them permanently leave the region", it said.

HRW added that the widespread killings raised the possibility that the RSF and their allies had "the intent to destroy in whole or in part" the Massalit people.

As this could constitute a genocide, it appealed to international bodies and governments to carry out an investigation.

A subsequent investigation by a UN team, external fell short of concluding that a genocide was taking place. Instead, it found that that both the RSF and army had committed war crimes.

However, the US determined in January this year that the RSF and allied militias have committed a genocide.

"The RSF and allied militias have systematically murdered men and boys - even infants - on an ethnic basis, and deliberately targeted women and girls from certain ethnic groups for rape and other forms of brutal sexual violence," then-Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said.

"Those same militias have targeted fleeing civilians, murdering innocent people escaping conflict, and prevented remaining civilians from accessing lifesaving supplies. Based on this information, I have now concluded that members of the RSF and allied militias have committed genocide in Sudan," he added.

This led to the US imposing sanctions on Gen Dagalo, followed by similar measures against Gen Burhan.

Sudan's government filed a case against the UAE in the International Court of Justice (ICJ), accusing it of being complicit in the genocide by funding and arming the RSF.

However, the ICJ refused to hear the case, saying that it had no jurisdiction over it.

The UAE welcomed its ruling, with an official saying that the Gulf state "bears no responsibility for the conflict", external. However, UN experts say allegations that the UAE is supporting the RSF are credible.

The RSF also denies committing genocide, saying it was not involved in what it describes as a "tribal conflict" in Darfur.

But the UN investigators said they had received testimony that RSF fighters taunted non-Arab women during sex attacks with racist slurs and saying they will force them to have "Arab babies".

With reports of atrocities, including massacres, now coming out of el-Fasher there are concerns about the fate of an estimated 250,000 people in the city, many from non-Arab communities.

What is being done to end the conflict?

There have been several rounds of peace talks in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain - but they have failed.

In early November, the RSF announced it had agreed to a humanitarian truce proposed by the US, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

However, the army said it would be wary of agreeing to a truce, accusing the RSF of not respecting ceasefires.

UN health chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has also lamented that there is less global interest in the conflict in Sudan, and other recent conflicts in Africa, compared to crises elsewhere in the world.

"I think race is in the play here," he told the BBC in September 2024.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) think-tank has called diplomatic efforts to end the war "lacklustre", while Amnesty International has labelled the world's response "woefully inadequate".

Humanitarian work has also been badly affected by the decision of the Trump administration to cut aid.

The WFP says more than 24 million people in the country are facing acute food insecurity.

Aid volunteers told the BBC that more than 1,100 - or almost 80% - of the emergency food kitchens have been forced to shut, fuelling the perception that Sudan's conflict is the "forgotten war" of the world.

Where are the weapons coming from?

There has been a UN arms embargo on the RSF's stronghold of Darfur since 2004, but it has not been extended to the rest of Sudan despite calls from human rights groups.

The flow of weapons into the country has been analysed by various experts.

Amnesty International says it has found evidence of weapons manufactured in Serbia, Russia, China, Turkey, Yemen and UAE being used in Sudan.

The smuggling route is often via the UAE, through to Chad, then into Darfur - according to a leaked report by UN experts, external.

The UAE in particular is accused of being the main provider of arms and support to the RSF, who in turn are accused of using the UAE as a marketplace for illicit gold sales.

As for the Sudanese Armed Forces, evidence suggests they have been supplied with weapons by Iran.

All parties deny these allegations.

In October 2025, the UK government came under fire from its own lawmakers following allegations that British-made weapons were ending up in the hands of the RSF, who were using them to commit atrocities.

In response to one MP's demand to "end all arms shipments to the UAE until it is proved that the UAE is not arming the RSF", Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper said at the time: "The UK has extremely strong controls on arms exports, including to prevent any diversion. We will continue to take that immensely seriously."

At a later summit of G7 foreign ministers, the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio also called for international action to cut off the supply of weapons to the RSF.

Where is Sudan?

Sudan is in north-east Africa and is one of the largest countries on the continent, covering 1.9 million sq km (734,000 sq miles).

It borders seven countries and the Red Sea. The River Nile also flows through it, making it a strategically important for foreign powers.

The population of Sudan is predominantly Muslim and the country's official languages are Arabic and English.

Even before the war started, Sudan was one of the poorest countries in the world - despite the fact that it is a gold-producing nation.

Its 46 million people were living on an average annual income of $750 (£600) a head in 2022.

The conflict has made things much worse. Last year, Sudan's finance minister said state revenues had shrunk by 80%.

More about Sudan's war from the BBC:

Inside Darfur: Siege and massacres

With unprecedented access inside Darfur, BBC World Service shares rare accounts of life in el-Fasher and investigates allegations of atrocities in Sudan’s civil war.

People outside the UK can watch the documentary on YouTube, external.

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

BBC Africa podcasts

- Attribution