Charity's warning over infected blood compensation

Cheyenne and Queste Usher were initially told their father's medical records were no longer available

- Published

A charity representing victims of the infected blood scandal said eight out of 10 people affected could have difficulty proving a case for compensation.

The Hepatitis C Trust said that only "a very small proportion" of people affected would be able to get financial support because of problems accessing medical records.

Like hundreds of others, Cheyenne and Queste Usher had struggled to get the paperwork to prove their father had received contaminated blood - and it was only after the BBC made enquiries that his records were found.

Gavin Usher, from Stevenage in Hertfordshire, contracted hepatitis C and died from liver disease in 2013 after receiving a blood transfusion in 1984.

'Daddy's sick'

Mr Usher needed the procedure at the Lister Hospital in Stevenage after suffering serious injuries in an assault.

Contaminated blood has led to the deaths of more than 3,000 people , externaland 30,000 were infected with hepatitis C and HIV after being given blood and blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

Mr Usher was a painter and decorator and was 48 years old when he died.

His daughter, Cheyenne, was 16 at the time and his son, Queste, was 18.

"We were always told we couldn't tell our friends that he had this disease [hepatitis C] because he was fearful their parents would stop them hanging around with us," said Mr Usher.

Ms Usher said that her earliest memories, aged four, were of her mother telling her that "daddy is sick".

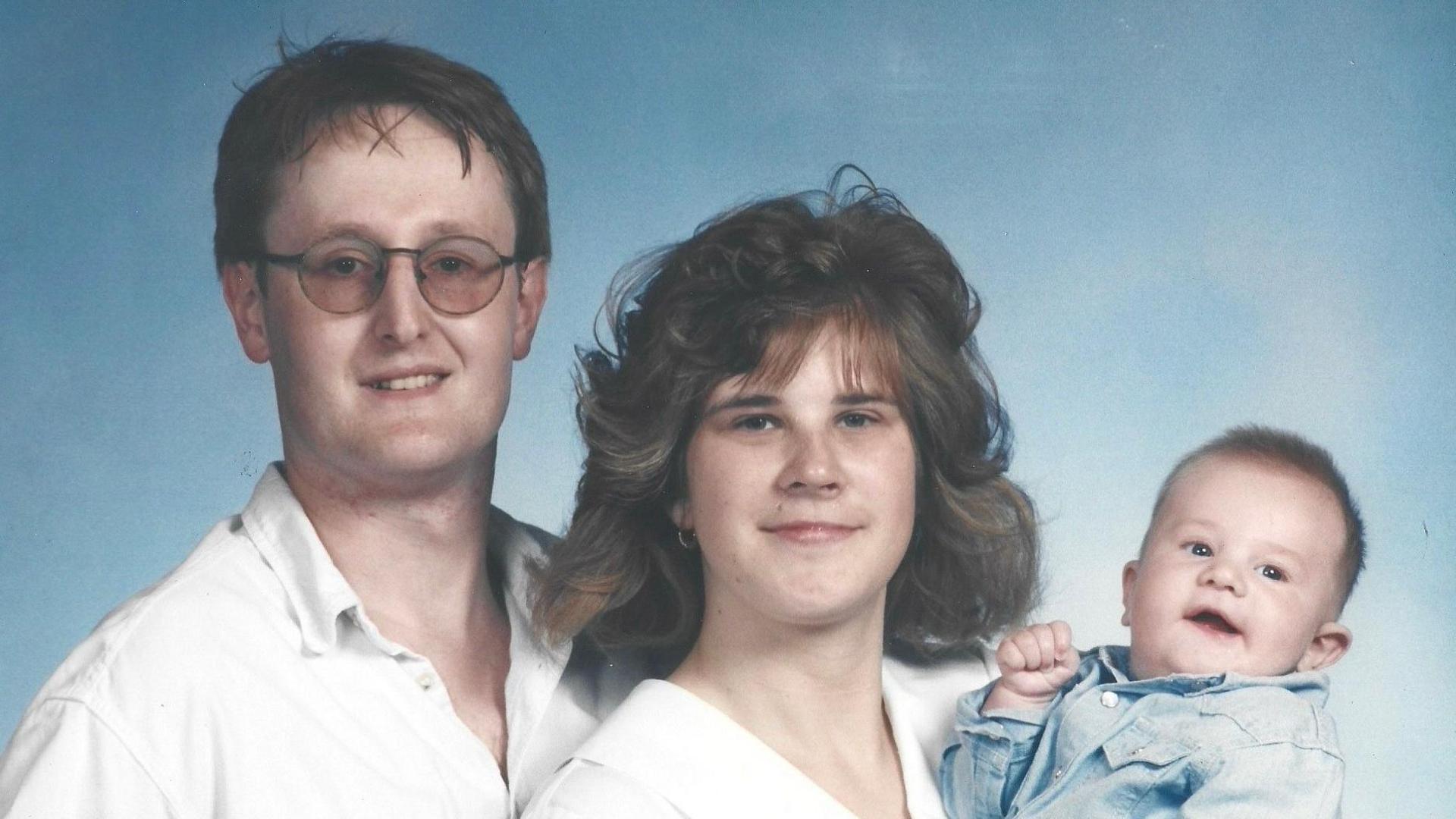

Gavin Usher was diagnosed with hepatitis C a few years after his son Queste was born

Her brother said their father knew something was wrong immediately after the transfusion.

"He said he felt dirty and had a nasty taste in his mouth. He was always adamant there was something wrong, even after he got the [hepatitis C] diagnosis 14 years later. But it wasn't spoken about back then," said Mr Usher.

Queste Usher says despite living with a serious liver infection, his father tried to make time for his children

Life 'spiralled'

As the scale of the national scandal emerged, the pair struggled to cope.

Mr Usher dropped down four school sets in two years and had an attendance of below 70%. He was often absent, helping his seriously ill father with hospital appointments.

Following his father's death, Mr Usher, who now lives in Cambridgeshire, said his life "spiralled". He became homeless and was remanded in prison for a short time.

His sister now works in healthcare and lives in Bedfordshire. Ms Usher said she wanted to train to become a child psychologist, so that she could help children with trauma.

She admitted that what happened with her father meant she was "terrified" about having to consent to a blood transfusion.

"That's not something I can handle, that's not something I can live with. My mother haemorrhaged with my brother and so I know it's a risk. It's an irrational fear, I'm aware of that, but it's a fear nonetheless," she said.

"I know blood is screened now, but I will continue to go through therapy for the rest of my life. You will never get out of any situation like this unscathed."

Ms Usher says even though blood is screened for diseases like hepatitis C now, she is still scared of needing a transfusion

Records destroyed

In July, the government announced that, from October, the estates of those who died as a result of the infected blood scandal could claim a £100,000 interim compensation payment, external if they hadn't already received one. But that payment will depend on evidence.

It was only after the siblings had worked through the trauma of losing their father that they discovered they would need medical records to prove their case. They said they were initially told the records had been destroyed.

But, after being contacted by the BBC, the trust that runs Lister Hospital said the records had been located in storage and were "still available".

Justin Daniels, medical director of the East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, said: "We would like to send our condolences to the family of Gavin Usher and those harmed through receiving infected blood.

"Whilst it is standard practice to destroy adult medical records eight years after a patient’s last treatment, in April 2019 the Infected Blood Inquiry requested that trusts do not destroy the medical records of relevant patients who have died.

"Mr Usher’s medical records are still available, and we encourage the family to get in touch with our medico legal team who can arrange access. We apologise for any wrong information given to Gavin’s family about his records."

While the Usher family may have had a breakthrough in their case, many more are struggling to access the information they need, a charity has warned.

Susan Lee, infected blood inquiry lead for the Hepatitis C Trust, said she heard concerns about missing records on a daily basis.

"It really is quite a widespread problem. We would say out of every ten cases we have, maybe eight of them have problems locating their records," she said.

She added that even if the patient was still alive, the lack of records was still an issue.

"We find eight years after treatment a lot of these medical records have been destroyed.

"It is incredibly pertinent to that person's medical history moving forward that medical records should be kept."

Expert evidence, external at the infected blood inquiry also found that medical records were unavailable because of incompetence, a lack of proper systems and problems with keeping paper records.

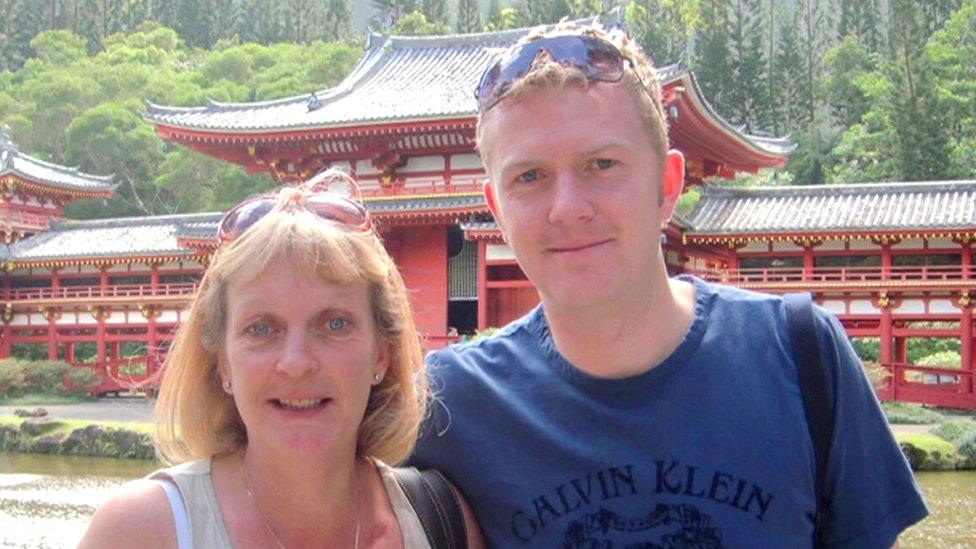

Susan Lee has herself contracted hepatitis C and now works to help others struggling for recognition

Ms Lee argues that the absence of a centralised database for blood transfusions or medical records often made any exercise to trace patients "insurmountable".

"There wasn't a proper look-back exercise to try and find the people at the time that were infected and obviously doing it 30 to 40 years later is a huge task," she said.

"If there was something set up across the UK to actually search [medical records] for these people, that would be hugely beneficial."

Ms Lee said that when those people affected do not have medical records, the compensation scheme "should take that into consideration".

An independent Infected Blood Compensation Authority, external is currently being set up.

A Government spokesperson said: “The scheme will be created with the community in mind and provide a compassionate and user-friendly service – while having the right checks and balances to protect against fraud”.

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Beds, Herts & Bucks?

Follow Beds, Herts and Bucks news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

Related topics

- Published22 April 2024

- Published23 May 2024

- Published9 May 2024

- Published20 May 2024