How hundreds of Irish babies came to be buried in a secret mass grave

- Published

No burial records. No headstones. No memorials.

Nothing until 2014, when an amateur historian uncovered evidence of a mass grave, potentially in a former sewage tank, believed to contain hundreds of babies in Tuam, County Galway, in the west of Ireland.

Now, investigators have moved their diggers onto the nondescript patch of grass next to a children's playground on a housing estate in the town. An excavation, expected to last two years, will begin on Monday.

The area was once where St Mary's children's home stood, a church-run institution that housed thousands of women and children between 1925 and 1961.

Many of the women had become pregnant outside of marriage and were shunned by their families - and separated from their children after giving birth.

According to death records, Patrick Derrane was the first baby to die at St Mary's – in 1925, aged five months. Mary Carty, the same age, was the last in 1960.

In the 35 years between their deaths, another 794 babies and young children are known to have died there - and it is believed they are buried in what former Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Enda Kenny dubbed a "chamber of horrors".

PJ Haverty spent the first six years of his life in the place he calls a prison - but he considers himself one of the lucky ones.

"I got out of there."

PJ Haverty, pictured at the garden where investigators will begin their excavations

He remembers how the "home children", as they were known, were isolated at school.

"We had to go 10 minutes late and leave 10 minutes early, because they didn't want us talking to the other kids," PJ said.

"Even at break-time in the school, we weren't allowed to play with them – we were cordoned off.

"You were dirt from the street."

Read more from the survivors, relatives and campaigners who helped reveal the secret of Tuam after a decades-long wait for the truth.

The stigma stayed with PJ his whole life, even after finding a loving foster home and, in later years, tracking down his birth mother, who was separated from him when he was a one-year-old.

The home, run by the nuns of the Bon Secours Sisters, was an invisible spectre that loomed over him and many others in Tuam for decades – until amateur historian Catherine Corless brought St Mary's dark past into the light.

Discovering the mass grave

Catherine Corless' shocking findings about the mass grave emerged in 2014

Interested in delving into her family's past, Catherine took a local history course in 2005. Later, her interest turned to St Mary's and the "home children" who came to school separately from her and her classmates.

"When I started out, I had no idea what I was going to find."

To begin with, Catherine was surprised her innocuous inquiries were being met with blank responses or even suspicion.

"Nobody was helping, and nobody had any records," she said.

That only fed her determination to find out more about the children at the home.

A breakthrough came when she spoke to a cemetery caretaker, who brought her to the housing estate where the institution once stood.

The grotto at the garden above what is believed to be the mass grave. People have left mementoes, messages and items of remembrance

At the side of a children's playground, there was a square of lawn with a grotto – a small shrine centred on a statue of Mary.

The caretaker told Catherine that two boys had been playing in that area in the mid-1970s after the home was demolished, and had come across a broken concrete slab. They pulled it up to reveal a hole.

Inside they saw bones. The caretaker said the authorities were told and the spot was covered up.

People believed the remains were from the Irish Famine in the 1840s. Before the mother-and-baby home, the institution was a famine-era workhouse where many people had died.

But that didn't add up for Catherine. She knew those people had been buried respectfully in a field half a mile away - there was a monument marking the spot.

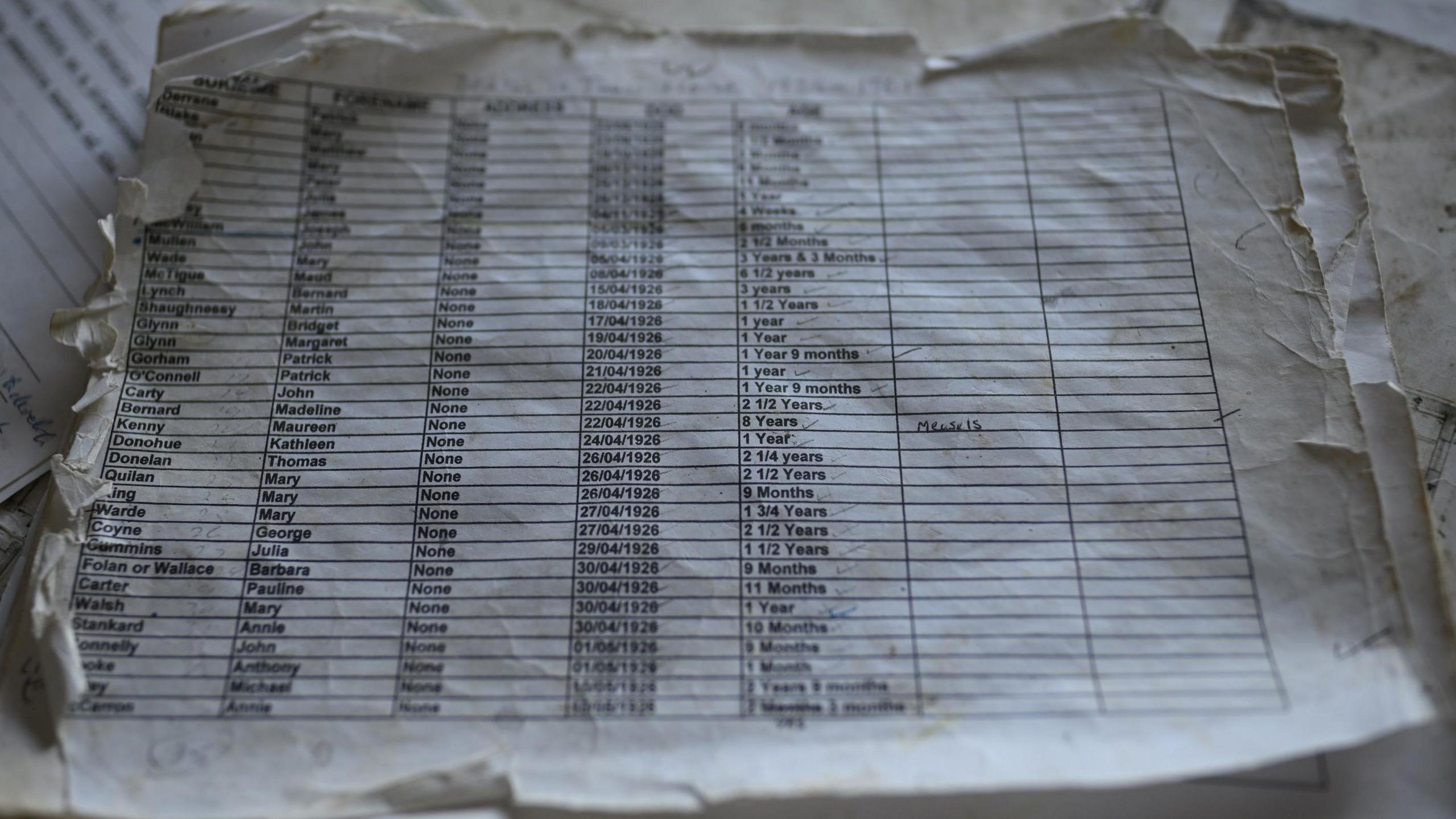

Catherine received a list recording hundreds of children's deaths at the St Mary's institution

Her suspicion was further raised when she compared old maps of the site. One, from 1929, labelled the area the boys found the bones as a "sewage tank". Another, from the 1970s after the home was demolished, had a handwritten note next to that area saying "burial ground".

The map did seem to indicate there was a grave at the site – and Catherine had read the sewage tank labelled on the map had become defunct in 1937 so, in theory, was empty. But who was buried there?

Catherine called the registration office for births, deaths and marriages in Galway and asked for the names of all the children who had died at the home.

A fortnight later a sceptical member of staff called to ask if she really wanted them all – Catherine expected "20 or 30" - but there were hundreds.

The full list, when Catherine received it, recorded 796 dead children.

She was utterly shocked. Her evidence was starting to indicate who was likely to be underneath that patch of grass at St Mary's.

But first, she checked burial records to see if any of those hundreds of children were buried in cemeteries in Galway or neighbouring County Mayo – and couldn't find any.

Without excavation, Catherine couldn't prove it beyond doubt. She now believed that hundreds of children had been buried in an unmarked mass grave, possibly in a disused sewage tank, at the St Mary's Home.

When her findings broke into an international news story in 2014, there was considerable hostility in her home town.

"People weren't believing me," she recalled. Many cast doubt - and scorn - that an amateur historian could uncover such an enormous scandal.

But there was a witness who had seen it with her own eyes.

Warning: The following sections contain details some readers might find distressing

Mary Moriarty lived in one of the houses built at the site of the home in the 1970s

Mary Moriarty lived in one of the houses near the site of the institution in the mid-1970s. Shortly after she spoke to BBC News, she passed away, but her family have agreed to allow what she told us to be published and broadcast.

Mary recalled two women coming to her in the early 1970s saying "they saw a young fella with a skull on a stick".

Mary and her neighbours asked the child where he had found the skull. He showed them some shrubbery and Mary, who went to look, "fell in a hole".

Light streamed in from where she had fallen. That's when she saw "little bundles", wrapped in cloths that had gone black from rot and damp, and were "packed one after the other, in rows up to the ceiling".

How many?

"Hundreds," she replied.

Some time later, when Mary's second son was born in the maternity hospital in Tuam, he was brought to her by the nuns who worked there "in all these bundles of cloths" - just like those she had seen in that hole.

"That's when I copped on," Mary says, "what I had seen after I fell down that hole were babies."

Anna Corrigan discovered her mother gave birth to two boys - John and William - in the home

In 2017, Catherine's findings were confirmed - an Irish government investigation found "significant quantities of human remains" in a test excavation of the site.

The bones were not from the famine and the "age-at-death range" was from about 35 foetal weeks to two or three years.

By now, a campaign was under way for a full investigation of the site - Anna Corrigan was among those who wanted the authorities to start digging.

Until she was in her 50s, Anna believed she was an only child. But, when researching her family history in 2012, she discovered her mother had given birth to two boys in the home in 1946 and 1950, John and William.

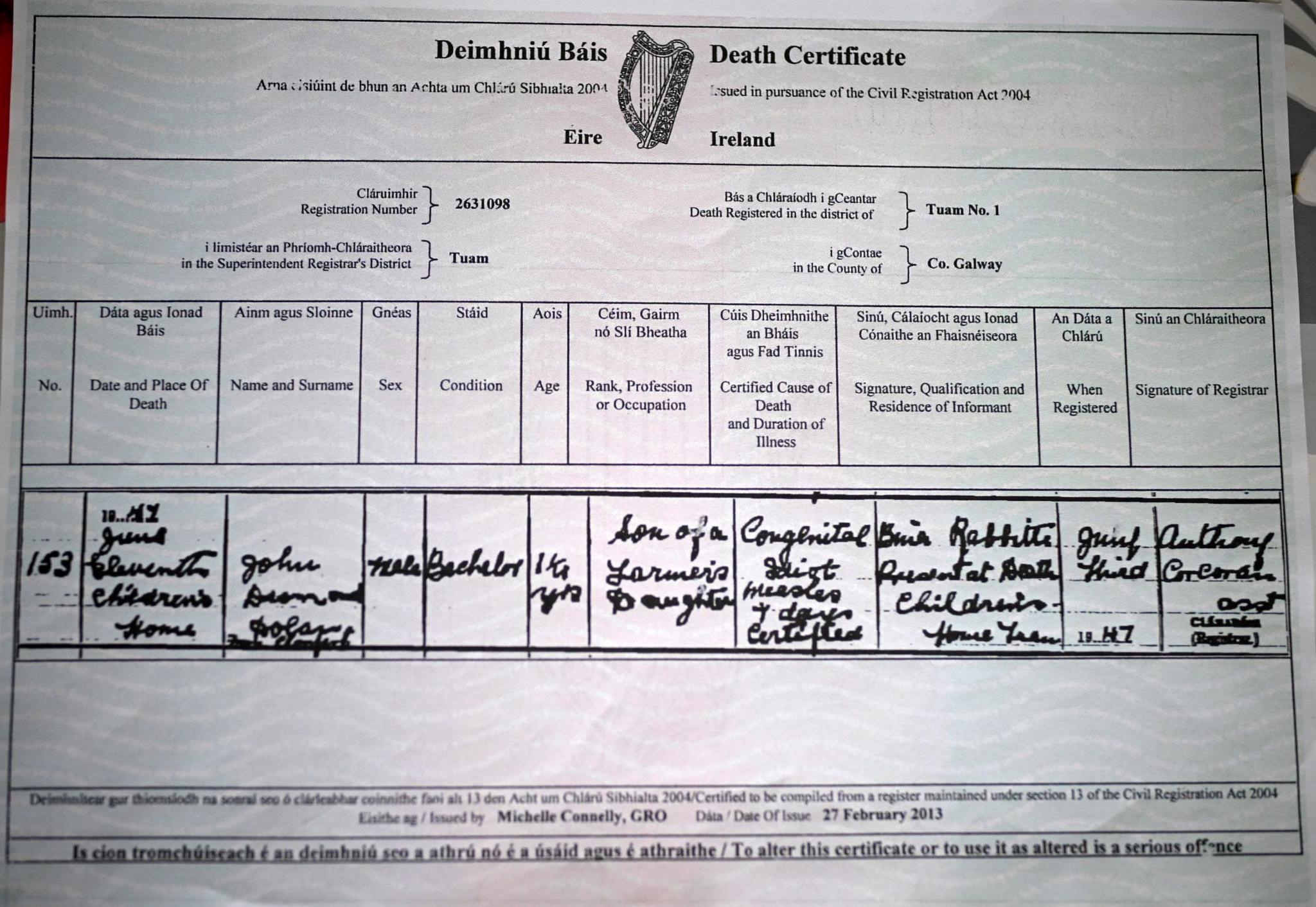

Anna was unable to find a death certificate for William, but did find one for John – it officially registers his death at 16 months. Under cause of death it listed "congenital idiot" and "measles".

The death certificate for John lists "congenital idiot" and "measles" under cause of death

An inspection report of the home in 1947 had some more details about John.

"He was born normal and healthy, almost nine pounds (4kg) in weight," Anna said. "By the time he's 13 months old, he's emaciated with a voracious appetite, and has no control over bodily functions.

"Then he's dead three months later."

An entry from the institution's book of "discharges" says William died in 1951 – she does not know where either is buried.

Anna, who set up the Tuam Babies Family Group for survivors and relatives, said the children have been given a voice.

"We all know their names. We all know they existed as human beings."

Now, the work begins to find out the full extent of what lies beneath that patch of grass in Tuam.

'Absolutely tiny'

Daniel MacSweeney, the head of the excavation, has previously been involved in searches for missing bodies in conflict zones around the world

The excavation is expected to take about two years.

"It's a very challenging process – really a world-first," said Daniel MacSweeney, the head of the operation, who has helped find missing bodies in conflict zones such as Afghanistan.

He explained that the remains would have been mixed together and that an infant's femur - the body's largest bone - is only the size of an adult's finger.

"They're absolutely tiny," he said. "We need to recover the remains very, very carefully – to maximise the possibility of identification."

The difficulty of identifying the remains "can't be underestimated", he added.

For however long it takes, there will be people like Anna waiting for news - hoping to hear about sisters, brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins they never had the chance to meet.

The Bon Secours Sisters, who ran the institution, apologies after the commission of the investigation published its full findings, saying: "We did not live up to our Christianity."

The organisation is making a contribution of about €13m (£11.1m) to a state compensation scheme for survivors of mother and baby-and-baby institutions. It is also giving another €2.5m ("2.14m) towards the cost of the excavation.

Galway County Council, which owned the institution, apologised for its role saying: "We acknowledge the sad and painful truth, the personal impact and the heavy burden carried by survivors and humbly acknowledge our failings."

Details of help and support with child bereavement are available in the UK at BBC Action Line

Related topics

- Published13 January 2021

- Published16 June

- Published12 January 2021

- Published24 May 2023

- Published12 January 2021