Noughties girl bands lift lid on inner workings of pop stardom

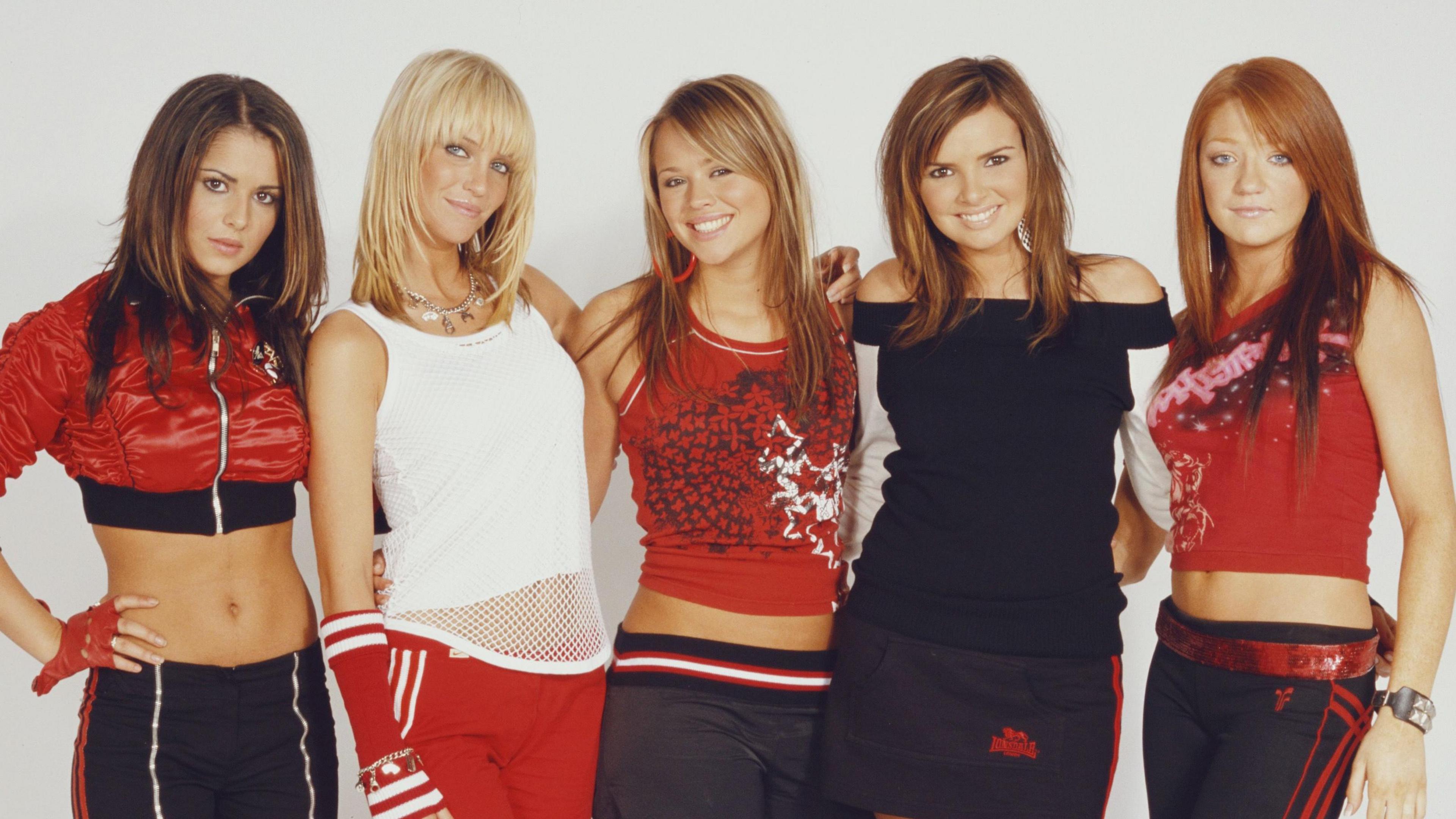

Girls Aloud, pictured shortly after winning Pop Stars: The Rivals in 2002 (L-R): Cheryl, Sarah Harding, Kimberley Walsh, Nadine Coyle and Nicola Roberts

- Published

"For my money, the best pop groups are girl bands," says Andy McCluskey, frontman of OMD and the mastermind behind Atomic Kitten.

"Boy bands are absolutely horrible. They only sell records because lovestruck girls have their poster on the bedroom wall."

Not the most sensitive observation, perhaps, but McCluskey - speaking to BBC News in 2010 - had a point.

With a few notable exceptions (Blackstreet, Five, One Direction), boy bands coast along on good looks and syrupy ballads that promise "Girl, I know you're the one, girl."

Their female counterparts, from The Ronettes in the 1960s to TLC in the 90s and Katseye in 2025, are more experimental, with more conceptual versatility and, frankly, better songs.

Just look at the anarchic energy of The Spice Girls' Wannabe, or the seven-part pop Frankenstein that was Girls Aloud's Biology and ask yourself, "Could Westlife have pulled that off?" (Hint: Not a chance).

But, for a long time, girl bands were the underdogs, dismissed as vapid and superficial. It took 41 years for an all-female act, in the form of Little Mix, to win best group at the Brit Awards.

The BBC documentary Girlbands Forever aims to set the record straight, celebrating all that melodic brilliance while revealing the darker side of the industry.

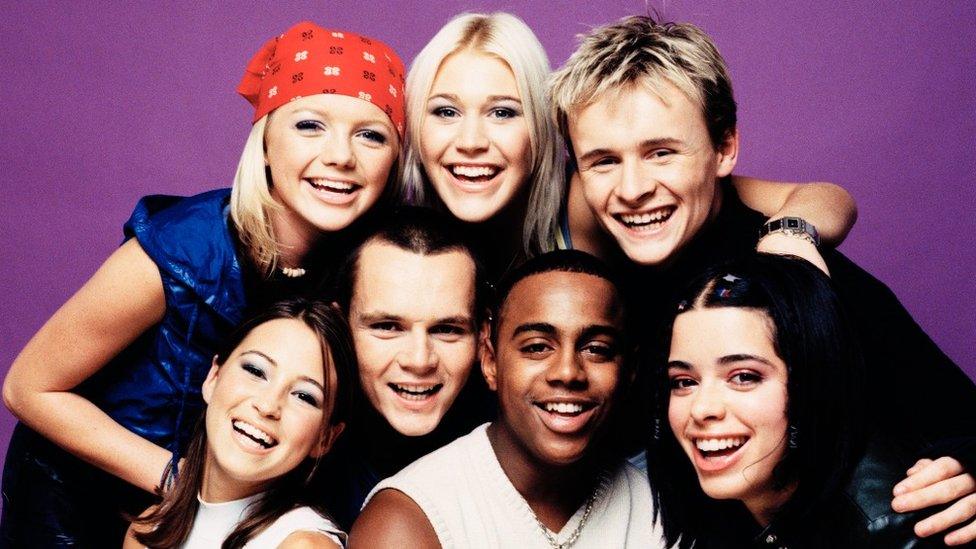

Sugababes were still teenagers when they released their first album, and had to juggle promotions with schoolwork

In the first two episodes, broadcast last week, Kelle Bryan of the 90s band Eternal recalls a gruelling boot camp where the band's diet was strictly controlled; while a tearful Melanie Blatt of All Saints describes being told to have an abortion in case her pregnancy jeopardised the band (she declined).

This Saturday's final episode focuses on the ever-changing line-up of the Sugababes; illustrating how callous the industry could be.

"It didn't really bother me that Sugababes had a revolving door, because sometimes the brand can be bigger than the individual, and Sugababes were a brand," opines Darcus Beese, former head of the band's record label, Island.

Looking at the group's 2009 line-up – which featured none of the original members – he makes a scathing observation: "I don't even think they were good [enough] to be a tribute band."

Across the documentary, the same story repeats itself, of young singers with high hopes, thrust into an unforgiving industry.

"People only see the glamorous side, but we worked incredibly hard," Atomic Kitten's Kerry Katona tells BBC News.

"At one stage, all three of us was on drips. We had no control and no say."

Girlbands Forever: Streaming now on BBC iPlayer (UK only)

In an unpublished interview from 2023, Girls Aloud told me a similar story of being cast adrift without an anchor.

Put together on ITV's reality show Pop Stars: The Rivals, they were left to fend for themselves, without a formal day-to-day manager for more than a year.

"It was chaos," said Nadine Coyle. "We were children and nobody was looking after us.

"The marketing team wanted us to do one thing, the live agent wanted us to do another, the TV team wanted us on breakfast TV. And there was nobody looking at the big picture and thinking, 'These girls are working 22 hours a day, seven days a week'."

Cheryl said the band were so clueless that they'd phone the head of their record label to tell him their washing machine had broken down.

"But in the end, we knew how every single part of the business worked," said Kimberley Walsh.

"It gave us a real strength of character," agreed Nicola Roberts. "We weren't afraid to say, 'No, we don't want to do this', because we had no middle man to hide behind."

'Feisty attitudes'

Other groups were less fortunate. Siobhan Donaghy was only 16 when the Sugababes' first single - the nonchalantly brilliant Overload - hit the Top 10. At the time, she had no idea how to speak up for herself.

"We were too young to know that we could make changes," she told me last year. "We didn't question anything, we just rolled with it.

"Now, if something's not working, we understand it's our business and we get everyone on the same page."

Su-Elise Nash, who was part of the R&B crossover act Mis-Teeq between 1999 and 2005, says the band's independence (they managed themselves and co-wrote all their songs) protected them from the worst of the industry.

"We were never scared to speak our mind and I think that feisty attitude steered us in the right direction," she laughs. "People knew they couldn't take the mick."

Inspired by US vocal harmony groups such as En Vogue and SWV, Mis-Teeq cleverly incorporated garage and hip-hop to their sound, with Alesha Dixon's rat-a-tat MC'ing setting them apart from more their pop rivals.

But despite achieving transatlantic success with songs including Why and Scandalous, the trio faced a constant battle with racism.

One record executive told Dixon, external that "black girls won't sell records in the UK", and the band found it harder than their white counterparts to secure press coverage.

"It wasn't blatantly, outrightly said that they didn't think three black girls would sell magazines, but that was the attitude of the people in power," says Nash, speaking from her home in Australia.

"Rather than being battered down by it. We just thought, 'Let's work harder to get their respect and eventually they'll come back begging for us to be on the front cover'."

Despite appearances, Mis-Teeq were one of the few girl bands to receive the NME's seal of approval

In contrast to Mis-Teeq, bands such as Girls Aloud and Atomic Kitten became unwilling cover stars, in an era where tabloid newspapers wouldn't think twice about splashing pictures of drunken and distraught pop stars on their front pages.

"There was around 40 paparazzi outside my house every day," says Katona, and they weren't looking for flattering portraits.

"When I had my first baby, Molly, they printed [my photo with] a circle of shame around my stretch marks," she recalls

"It messes your head up. It made me suicidal. I didn't know how else to cope with it, so I turned to drugs.

"If I didn't have my children, I guarantee it, I would not be sat here today."

The harassment, and a string of revelations about her private life, ultimately prompted her to quit the band.

"I realised I didn't want the fame or the riches. I wanted to be a mum and a wife. Being a kid from foster home, that was all I actually craved."

The dream also came to a premature end for Su-Elise Nash. Mis-Teeq were in the middle of recording their third album when their label, Telstar, went bankrupt.

"It was a tough position to be in," she says. "They went into administration owing us a lot of money."

The band, in the middle of an exhausting six-month tour, decided to call it a day.

"In the same week, my grandmother got diagnosed with thyroid cancer and given months to live," says Nash. "So I got to spend those last six months with her, without having to go back to America, and do all those things that were in the diary,

"I don't have any regrets, because that's time I would never have got back."

Now 45, Kerry Katona has put her highly-publicised problems behind her, saying: "I've had my falls, but it's about the getting back up that counts"

The industry has matured since the girl band explosion of the early 2000s. Today, there's a wider awareness about mental health, and more efforts to mitigate the pressures facing young stars.

When Little Mix launched a TV talent show in September 2020, they insisted that the BBC provided aftercare for the contestants.

"We didn't have that, really, on the show that we came from," said Leigh-Anne Pinnock, referring to the band's experiences on The X Factor.

"It was all just go, go, go," agreed Jesy Nelson. "I personally don't feel like there was anyone who cared."

That said, girl groups still maintain shocking schedules. K-pop idols Le Sserafim recently told me they rehearse six hours every day, before fulfilling their other obligations in recording sessions, TV shows, and creating social media content.

So it's no surprise there's a bond between people who've survived the process.

"After the first episode of the documentary went out, I woke up to lovely messages from [Atomic Kitten's] Natasha Hamilton and Keisha from the Sugababes," says Su-Elise Nash.

"There's a lot of good feeling between the girls. It's not a catty, bitchy rivalry."

"And since doing the documentary, it's really resonated with me just how much work we put in and how many attitudes we changed, how many barriers we broke down.

"So when I look back, I feel proud. I feel really proud."

- Published22 November 2023

- Published28 March 2023

- Published27 June 2024