Swinney rejects calls for inquiry into Sturgeon investigation

- Published

John Swinney has rejected calls for a judge-led public inquiry into the running of an investigation into whether his predecessor Nicola Sturgeon broke the ministerial code.

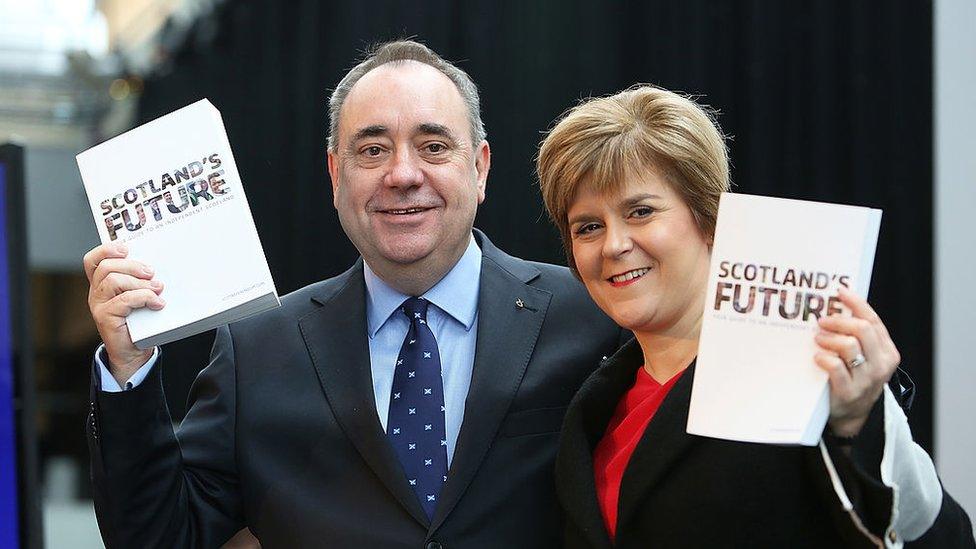

Ms Sturgeon was cleared of breaching the code by independent advisor James Hamilton in 2021, during the row over the government’s investigation of Alex Salmond.

Newly published legal advice in a separate row about freedom of information requests raises questions about the probe's independence, according to opposition MSPs

A Scottish government civil servant was seconded to work for Mr Hamilton and continued to correspond with Mr Swinney. The first minister said this was normal practice, and only dealt with practical matters.

The Conservatives and Labour both called for a judge-led public inquiry to be held, but Mr Swinney said he had “absolutely no intention” of agreeing to that.

This row has its roots in 2020, when Nicola Sturgeon submitted herself for an investigation by an independent advisor, the Irish lawyer James Hamilton, to determine whether she had broken the ministerial code.

Her government had just conceded a civil court case to Alex Salmond, paying him half a million pounds in costs, and the first minister ordered a review of her dealings with her predecessor.

Mr Hamilton ultimately concluded that Ms Sturgeon had not breached the code, although he voiced frustration that parts of his final report were heavily redacted for legal reasons.

Judge throws out bid to withhold Sturgeon evidence

- Published6 December 2023

Salmond launches action against Scottish government

- Published24 November 2023

Sturgeon cleared of breaching ministerial code

- Published22 March 2021

A member of the public - Benjamin Harrop - submitted a Freedom of Information request asking to see the submissions made to Mr Hamilton’s inquiry.

The government refused, claiming that they did not “hold” the material because it had been gathered by a separate “secretariat” working for Mr Hamilton.

The problem was that it had been stored on Scottish government IT servers.

After an appeal from Mr Harrop, the Information Commissioner - who oversees FOI law in Scotland - ruled that the government did indeed hold the information.

Ministers disagreed, and appealed that ruling in court. A trio of judges threw the appeal out in very short order, without even leaving the courtroom to confer.

Mr Harrop then made a fresh request to see the legal advice which prompted ministers to lodge that appeal - which is what brings us to the material which has now been made public.

It is rare to get to see legal advice; it usually remains private for the simple reason that lawyers are less likely to give frank, unvarnished analysis if they think it is going to end up in the newspapers.

The last time the government published legal advice around the Salmond row, during the Holyrood inquiry, some damning material was released.

A pair of the country’s most senior lawyers voiced “dismay” at the government’s handling of the judicial review brought by Mr Salmond, having suffered “extreme professional embarrassment” in court. They ultimately threatened to resign if the case was not conceded.

This new material, by comparison, is relatively mild.

FOI legal battle

KC James Mure did warn that “on balance, the court is more likely than not to refuse the appeal” if judges decided to take a “broad approach”.

The documents also show that the director of the government’s internal legal directorate, Ruaraidh Macniven, felt that “in his view this perhaps isn’t a case where ministers should appeal”.

However a significant intervention on the other side was made by the Lord Advocate, the government’s senior legal advisor, who “indicated that she thought the decision [of the Information Commissioner] should be tested”.

Dorothy Bain KC said there were “sound arguments” to make that the information acquired or generated by Mr Hamilton’s inquiry was not “held on behalf of Scottish ministers” under the terms of FOI law.

This was a view shared by ministers.

Minutes show that Mr Swinney - then the deputy first minister - was concerned that publishing the material “stretched the definitions” of Freedom of Information rules, and that it “needs to be tested” in court.

He said that simply conceding the case could mean a “significant shift” in how the government interpreted FOI law, and by not appealing it would “lose the opportunity to seek clarification on the points of law”.

There was an additional row about the information that ministers had provided to the Information Commissioner early in the case, having claimed that data stored on its servers was “accessible only to the secretariat” working for Mr Hamilton.

That turned out to be “not strictly accurate”, because some records were stored on a personal drive which ten other officials had access to - so information security was not as tight as had been claimed.

Mr Mure demanded ministers correct the “slightly false impression given by the original submissions”, and warned that this revelation also meant they were left with a “relatively weak case” in the appeal.

The investigation into Salmond led to his trial in Edinburgh in 2020

The KC did present the case himself in the Court of Session, but he turned out to be correct about the chances of success.

The dispute has moved smoothly on to new territory thanks to yet another aspect of the legal advice published - the role of the “secretariat” working for Mr Hamilton.

A civil servant from the Scottish government was seconded to support the Irish lawyer.

Mr Swinney says this is entirely normal practice, and was known about at the time.

But opposition leaders have cried foul about the fact there continued to be contact between that civil servant and her employers in the Scottish government - namely Mr Swinney - because she also acted in a “liaison” role.

The legal advice from James Mure says that while it may have been standard practice, it was “somewhat unfortunate that more distance was not enforced” between the secretariat and the government.

He said some of the correspondence he had seen “suggests a less than arm’s length and independent position”.

Labour MSP Jackie Baillie said this raised “huge questions” about the independence of the investigation, and indeed for any other inquiries which involve seconded civil servants.

Both she and Conservative leader Russell Findlay have called for a judge-led inquiry into what went on - something Mr Swinney has rejected.

The first minister read out a list of examples of contact between himself - as “sponsor” of the Hamilton investigation - and the civil servant.

They were things like coordinating correspondence from opposition MSPs, arranging to pay for legal advice for Mr Hamilton, and - somewhat ironically - dealing with freedom of information requests.

Mr Swinney stressed that he had absolutely no sight of anything in Mr Hamilton’s report until it was completed and delivered to the government.

And he said the employee - who was a career civil servant in a junior role, rather than a political appointee like a special advisor - was of ”impeccable record and repute”, and that it would be inappropriate to question her integrity.

Angry exchanges

Tuesday's parliamentary debate ended in rather angry exchanges when Swinney called out Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar for talking about the issue in the media, without turning up to face him in person in the Holyrood chamber.

So where does this rather convoluted row go from here?

It does not, to look back to the original FOI request, mean any material will actually be released.

Losing the appeal in theory meant ministers were meant to reconsider the original application.

But they could employ a whole range of other get-out clauses within the FOI rules - known as “exemptions” - to either refuse release or to redact the papers down to blank pages.

Indeed this is nodded to in the advice - a note from a government lawyer stresses that conceding the case “would not put the information at risk of inappropriate disclosure as other exemptions…are available to ministers”.

It also does not mean anything for Mr Hamilton’s decision - the Alba Party had called for Nicola Sturgeon to be re-investigated, but former ministers are not subject to the discipline of the ministerial code.

And Mr Swinney has been clear that there will not be a fresh inquiry.

That could potentially change if all of the opposition parties were to gang up on the minority SNP administration - which is what happened during the original Salmond inquiry, forcing the previous release of legal advice.

But the Greens do not seem particularly excited about the process, with Lorna Slater saying MSPs have “completely lost sight” of the original issue about harassment reporting processes.

There may well be further parliamentary clashes, FOI requests and legal opinions, but it is hard to see a clear route for the dispute to make any progress from here.

- Published23 March 2021

- Published22 March 2021