The evolution of devolution: 25 years of the Scottish Parliament

SNP MSP Winnie Ewing opened the Scottish Parliament for business in 1999

- Published

The King and Queen are at Holyrood this weekend to attend a celebration marking 25 years since the Scottish Parliament was “reconvened”.

That is how their visit is described in the official news release. Reconvened was the word that MSP Winnie Ewing chose when opening the devolved parliament for business in 1999.

As a nationalist politician, Mrs Ewing may have enjoyed the sense of historical continuity with the 18th Century parliament of what had been an independent Scotland.

Her choice of words raised a few eyebrows at the time because the new parliament bares little resemblance to the old one. The continuity is mostly myth.

Firstly, Holyrood is a democratically elected house rather than an assembly of aristocrats and the landed gentry.

Secondly, it represents an experiment in power-sharing within the United Kingdom, rather than a departure from the political Union with England of 1707.

Queen Elizabeth attended the state opening of the parliament in July 1999

For Labour, the party that delivered devolution, one of the key objectives of having more decisions about Scotland made in Scotland was to quell nationalist demands for full independence.

Labour’s shadow Scottish secretary before the 1997 general election, George Robertson, predicted devolution would “kill the SNP stone dead”.

By contrast his Labour MP colleague Tam Dalyell, who opposed devolution, warned that it would become a “motorway without exit to a separate state”.

Either could yet be vindicated but so far both have been wide of the mark.

Ten years ago this month, Scottish voters rejected the offer of independence in a referendum.

Of course, that referendum only materialised because a few years earlier, the main party of independence - the SNP - won an outright majority of seats in the Scottish Parliament.

Will spending cuts end Scotland's 'free for all' policies?

- Published17 August 2024

The birth of a parliament

- Published8 September 2017

The voting system was specifically designed for that not to happen. An element of proportional representation was supposed to require minority parties to cooperate and share power.

That’s what happened in the first eight years when Labour and the Liberal Democrats ran coalition governments.

Far from killing the SNP, Holyrood has given the party a platform to propel itself from protest to power.

Over the last 17 years, the SNP has become the dominant force in Scottish politics, keeping constitutional politics to the fore.

That has frustrated their opponents, who would prefer to have seen far greater focus on delivery and reform of devolved public services like the NHS and schools.

The SNP’s unsuccessful pursuit of independence has led to Holyrood accumulating new responsibilities.

It has become a more powerful parliament, with almost full control over income tax and the beginnings of a distinctive welfare system.

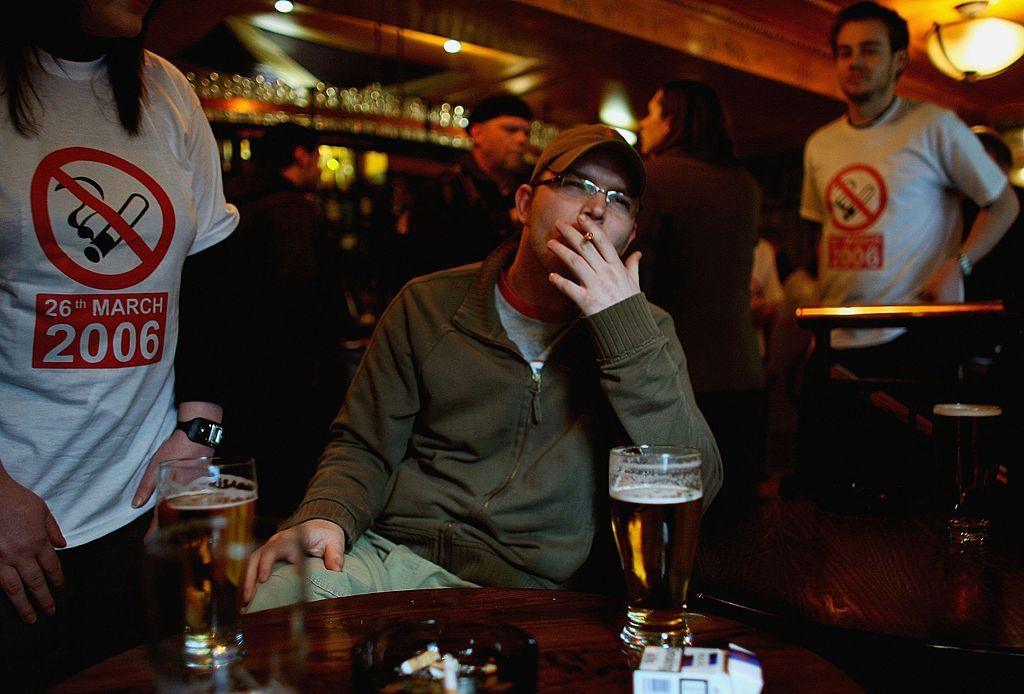

Smoking in public places was banned 2006

Not that it was without considerable clout. Just think of the life and death decisions made daily by Holyrood ministers during the Covid pandemic.

The parliament has passed 370 bills, including landmark legislation to ban smoking in enclosed public places, to introduce minimum unit pricing for alcohol, and to legalise same sex marriage.

A hallmark of devolution is that successive governments have expanded the provision of free or subsidised entitlements.

These include free personal care for the elderly, free prescriptions and free university tuition.

As budgets come under increasing pressure there is a sense that these provisions cannot be expanded much further and may need to become more targeted.

Holyrood has been good at spending money. It is less obviously accomplished at growing the economy to generate extra cash to pay for public services.

The bulk of its funding has always come from a block grant from the UK Treasury.

The Supreme Court was asked to rule on whether a referendum could take place without UK government approval

While some of its powers have expanded, the introduction of a UK internal market act following Brexit allowed the last Westminster government to block the introduction of a Scottish bottle deposit scheme.

UK ministers also used their reserved powers to stop gender recognition reforms in Scotland and were backed up by the courts.

In a separate dispute, their lawyers argued successfully in court that Holyrood could not hold another independence referendum without their approval.

As Scottish Secretary, Conservative MP Alister Jack was quite happy to be seen as a muscular unionist, checking the nationalism of the SNP.

These clashes poisoned relations between the Scottish and UK governments.

There appears to be an attempt at a reset following the general election, which saw the SNP lose lots of seats and Labour return to power at Westminster.

Labour supporters celebrate their victory at this year's general election

These struggles probably say more about the parties in power at Scottish and UK levels at a given time than they do about the the Scottish Parliament itself.

That is not to deny there is scope to revise the way Holyrood operates to make it better equipped to hold the Scottish government of the day to account.

All parties that have been consistently represented at Holyrood have had a shot in government, except for the Conservatives.

It was Labour’s one time Welsh secretary, Ron Davies, who was fond of saying that devolution was a process, not an event.

There has been much evolution in the first 25 years and no doubt more to come.

There were points in the early years when the Scottish Parliament’s continued existence seemed far from secure.

It got off to a shaky start with the sudden death of the founding first minister, Donald Dewar; the resignation of his successor, Henry McLeish, in a property sub-letting row; and the scandalous delays and cost increases to the Holyrood parliament building project.

The building of the parliament was beset by delays and cost increases

It fell to Labour First Minister Jack McConnell to steady the ship. His SNP successors, Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon, expanded the boundaries of devolved power.

The spectacular fallout between Salmond and Sturgeon gripped Holyrood journalists for many months.

It was probably not something Donald Dewar had anticipated.

In his opening address to the parliament in 1999, he described the institution as “a new voice in the land”.

Twenty-five years later, there is little of consequence in Scotland that does not get discussed there. It is where people come to petition and protest. A traipse to London is no longer a necessity.

Holyrood has firmly established itself at the centre of Scottish public life.

Few would doubt that it is here to stay - and that, perhaps, is a significant achievement in itself.