Scottish devolution referendum: The birth of a parliament

- Published

Scottish devolution vote from the archive

Next Monday marks the 20th anniversary of the 1997 devolution referendum, which led to the creation of the devolved Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh.

I've been looking back at that historic day - and asking some of the key players about whether the parliament has met their expectations.

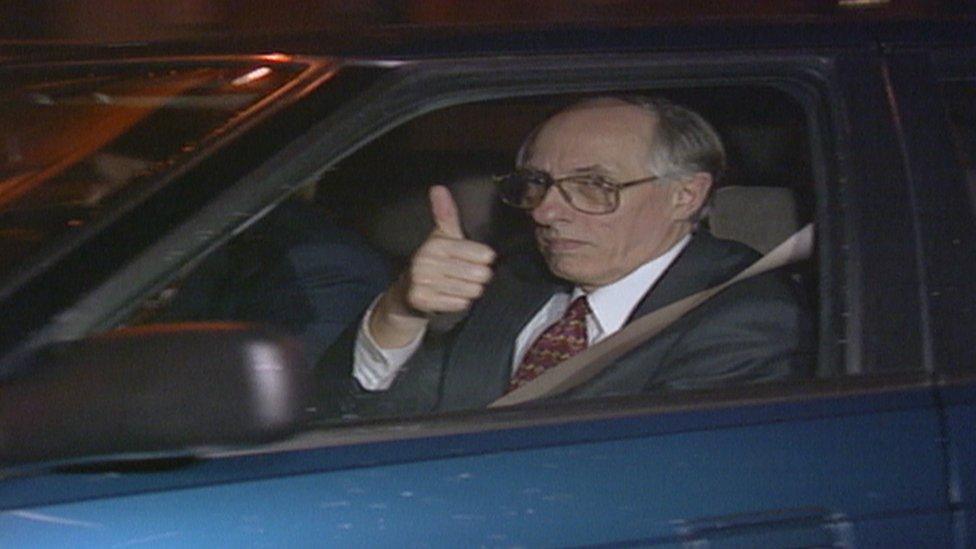

The then prime minister Tony Blair flies into Edinburgh - outside the left hand-side window of the helicopter there are stunning views of the castle.

On landing at Holyrood, he meets the Scottish secretary, the late Donald Dewar.

"Satisfactory, I think," Dewar says.

"Very satisfactory, and well done," Mr Blair replies.

Meanwhile, up the Royal Mile, an appreciative audience watches a drumming group as the occasion is marked, before both the prime minister and the Scottish Secretary speak.

Tony Blair arrived in Edinburgh by helicopter after the result of the referendum was announced

The previous day, on 11 September 1997, Scotland had voted overwhelmingly in support of a Scottish Parliament being created - and for that parliament to have tax varying powers.

Even though Labour won a landslide victory in the general election just a few months earlier, Mr Blair had wanted a referendum so his devolution legislation could be made legitimate with the people's backing, the votes of the folk gathered outside the old parliament.

The Liberal Democrats, among others, had considered a referendum unnecessary.

Real struggles

Nevertheless, when Donald Dewar as Scottish Secretary went back to Whitehall to get to work, he faced real struggles as civil service mandarins were sometimes unwilling to give up powers - despite the vote of the Scottish people.

The former Scottish Labour leader Wendy Alexander advised Mr Dewar at the time.

Speaking ahead of the 20th anniversary of the referendum, she told me: "It was a battle because many Whitehall departments were highly sceptical of whether it made sense to devolve back to Scotland areas that they had hitherto been in charge of.

"So there was a huge amount of official scepticism about whether matters beyond those of education, health and housing should also come to Scotland."

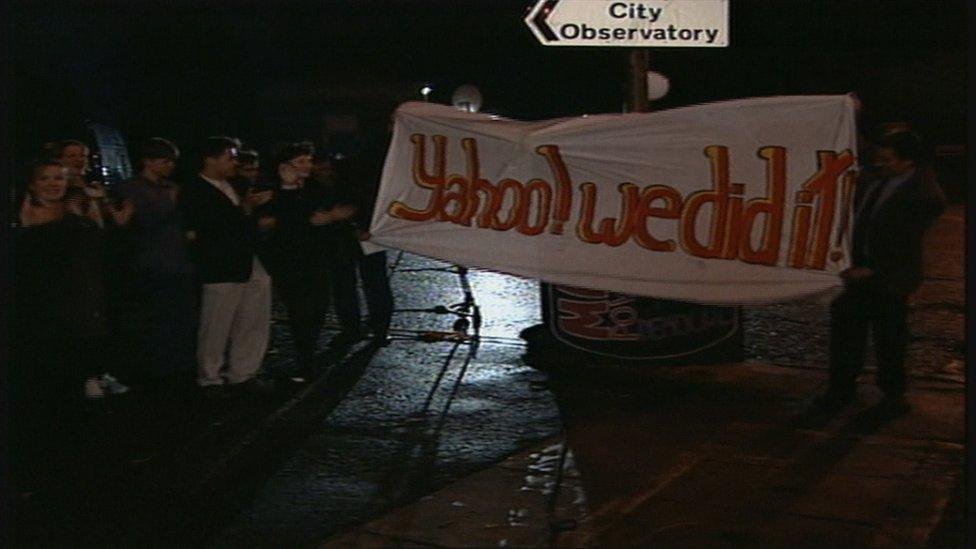

The size of the victory, and the 60% turnout, exceeded the expectations of pro-devolutionists such as Donald Dewar

Ms Alexander also says that it was up to the Labour government to do the heavy lifting on difficult issues that the Scottish Constitutional Convention had failed to address, such as the role of the Queen or aspects of tax-raising powers.

On St Andrew's Day 1995, what's regarded as many as a "blueprint" for the new parliament was signed with great pomp and ceremony in the General Assembly hall - which eventually became the seat of the parliament when it opened in 1999, before the parliament later moved into its new home at Holyrood.

Jim Wallace, now Lord Wallace, the former Scottish Liberal Democrat leader, rejects any suggestion that the blueprint was lacking.

He said: "The Constitutional Convention put forward a very comprehensive package - it's hard to think that there was any major question that it didn't actually address.

"Compare the convention's final report with what the government put forward in its White Paper and the overlap is considerably greater than anything that was added on or changed by the Labour government".

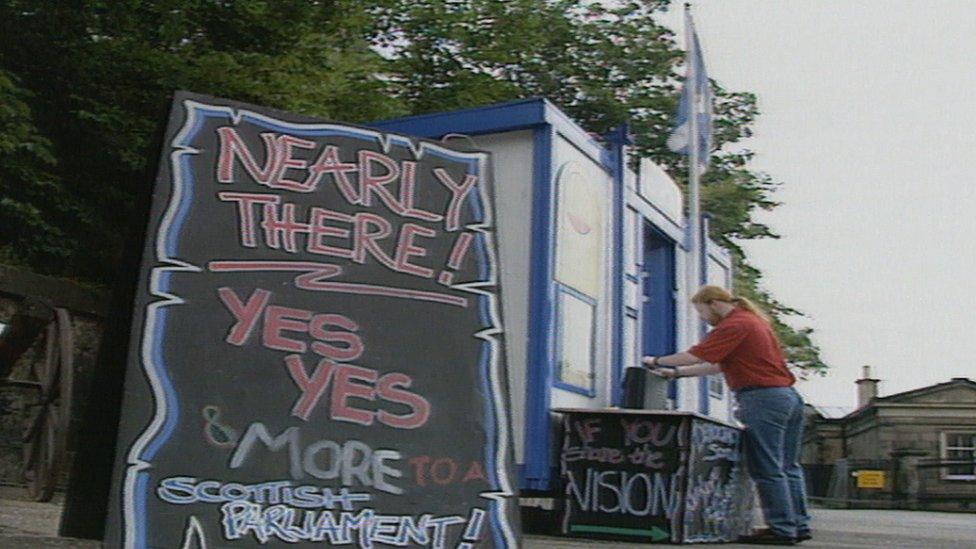

Devolution campaigners maintained a vigil on Calton Hill in Edinburgh for five years before the referendum

Voters backed the creation of a parliament by 74% to 26%, and for it to have tax powers by 63% to 37%

With that document on the table in 1995 and a Labour government in May 1997, it was perhaps inevitable what was going to happen.

Campaigning was suspended in August and early September following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales.

But when the people went to the ballot box, it was a landmark moment for Scotland, according to the historian Prof Tom Devine.

'Most significant development'

"It was the most significant development in Scottish political history since the Union of 1707. That is completely undeniable.

"It certainly was an important catalyst, a precondition - not necessarily a cause - but a pre-condition for developments which have taken place, including, of course the most recent referendum on independence," he said.

Prof Devine raises a point about the progress of independence without devolution. Perhaps Scots could have been galvanised to back it if Westminster rule had continued?

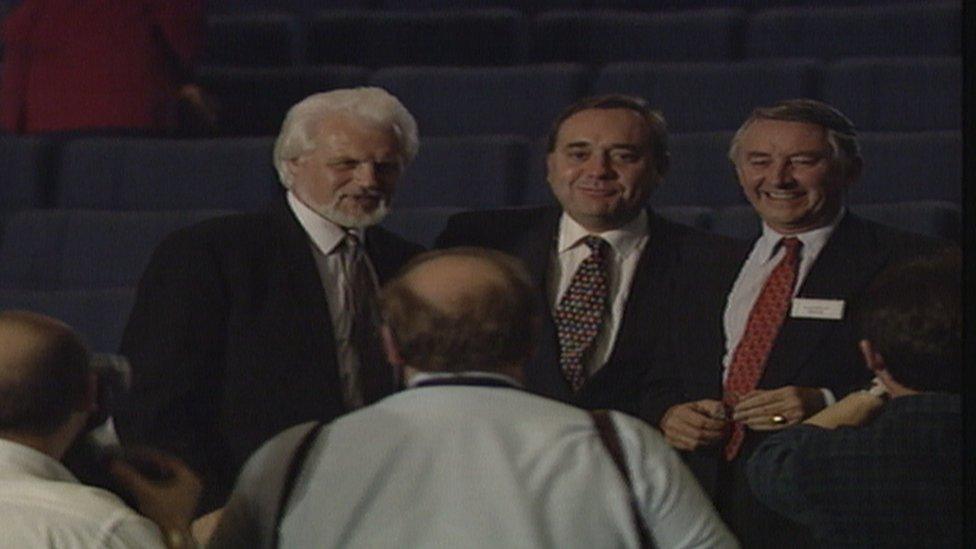

Alex Salmond and the SNP had initially been suspicious of the devolution proposals - but later backed the campaign

The SNP were suspicious of devolution, regarding it as a dead end for their constitutional ambitions, and had withdrawn from the convention.

Speaking to me in the Garden Lobby at Holyrood, the Brexit minister Mike Russell, a former chief executive of the SNP, told me why the party later changed its mind.

Mr Russell said: "Dewar made a commitment to us that there would be no glass ceiling in the bill. So, whatever the Scotland bill had, it would have nothing that actually stopped the progress to independence.

"It wouldn't enable it, there would be no mechanism to make it happen - but it wouldn't stop it. That was the commitment that made a difference and to pay tribute to Dewar, he knew with that commitment made, the SNP would be able to take part and there would be a united campaign."

Of course, the Conservatives continued with their opposition during the 1997 campaign.

'Seeking independence'

They've moved with the times, now making devolution work for them - with Ruth Davidson leading her party to second place at the Holyrood election last year.

But some of the former campaigners against devolution continue to warn about what they see as its dangers.

Donald Findlay QC, a prominent advocate and leading light in the No-No campaign, says: "Our parliament is not sovereign because it's restricted in what it can do.

"But the notion of a parliament creates in people the idea, well if we have a parliament, why don't we just have a parliament that deals with everything and a parliament that deals with everything is the equivalent to seeking independence."

Twenty years later, the debate over Scotland's constitutional future continues

Here's another interesting take from a fellow veteran campaigner. At his home in the Campsies, I caught up with Nigel Smith, who instigated and led the cross-party Yes-Yes campaign.

Ardently pro-devolution, he considers himself apolitical and has a withering assessment of all the parties who have been in power at Holyrood.

"I would give it six out of ten - a pass but not as good as I hoped it would be", he reveals.

"I think it's in the big areas of policy-making, like education, health, the economy where I feel disappointed a bit by the parliament.

"It's done quite a number of good things in all of these areas and yet it doesn't amount to the sort of improvement I expected to see."

Maybe expectations were too high back in 1997 and 1999, when the current parliament first met.

As I sit here typing this in the BBC office at the Scottish Parliament, First Minister's Questions is just about to start.

The chamber is just along the corridor and journalists are streaming into the press gallery and the public benches are filling up.

Like it or not, 20 years on, Holyrood is now the beating heart of the nation's politics.