Russian drones hunt civilians, evidence suggests

See evidence of drone strikes in Kherson authenticated by BBC Verify - some are too graphic to show

- Published

Just before noon one day Serhiy Dobrovolsky, a hardware trader, returned to his home in Kherson in southern Ukraine. He stepped into his yard, lit a cigarette and chatted with his next-door neighbour. Suddenly, they heard the sound of a drone buzzing overhead.

Angela, Serhiy's wife of 32 years, says she saw her husband run and take cover as the drone dropped a grenade. "He died before the ambulance arrived. I was told he was very unlucky, because a piece of shrapnel pierced his heart," she says, breaking down.

Serhiy is one of 30 civilians killed in a sudden surge in Russian drone attacks in Kherson since 1 July, the city’s military administration told the BBC. They have recorded more than 5,000 drone attacks over the same period, with more than 400 civilians injured.

Drones have changed warfare in Ukraine, with both Ukraine and Russia using them against military targets.

But the BBC has heard eyewitness testimony and seen credible evidence that suggest Russia is using drones also against civilians in the frontline city of Kherson.

"They can see who they are killing," says Angela. "Is this how they want to fight, by just bombing people walking in the streets?"

If Russia is found to be intentionally targeting civilians, it would be a war crime.

The Russian military did not respond to the BBC’s questions about the allegations. Since its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia has consistently denied deliberately targeting civilians.

Angela says she saw a drone kill her husband outside their house

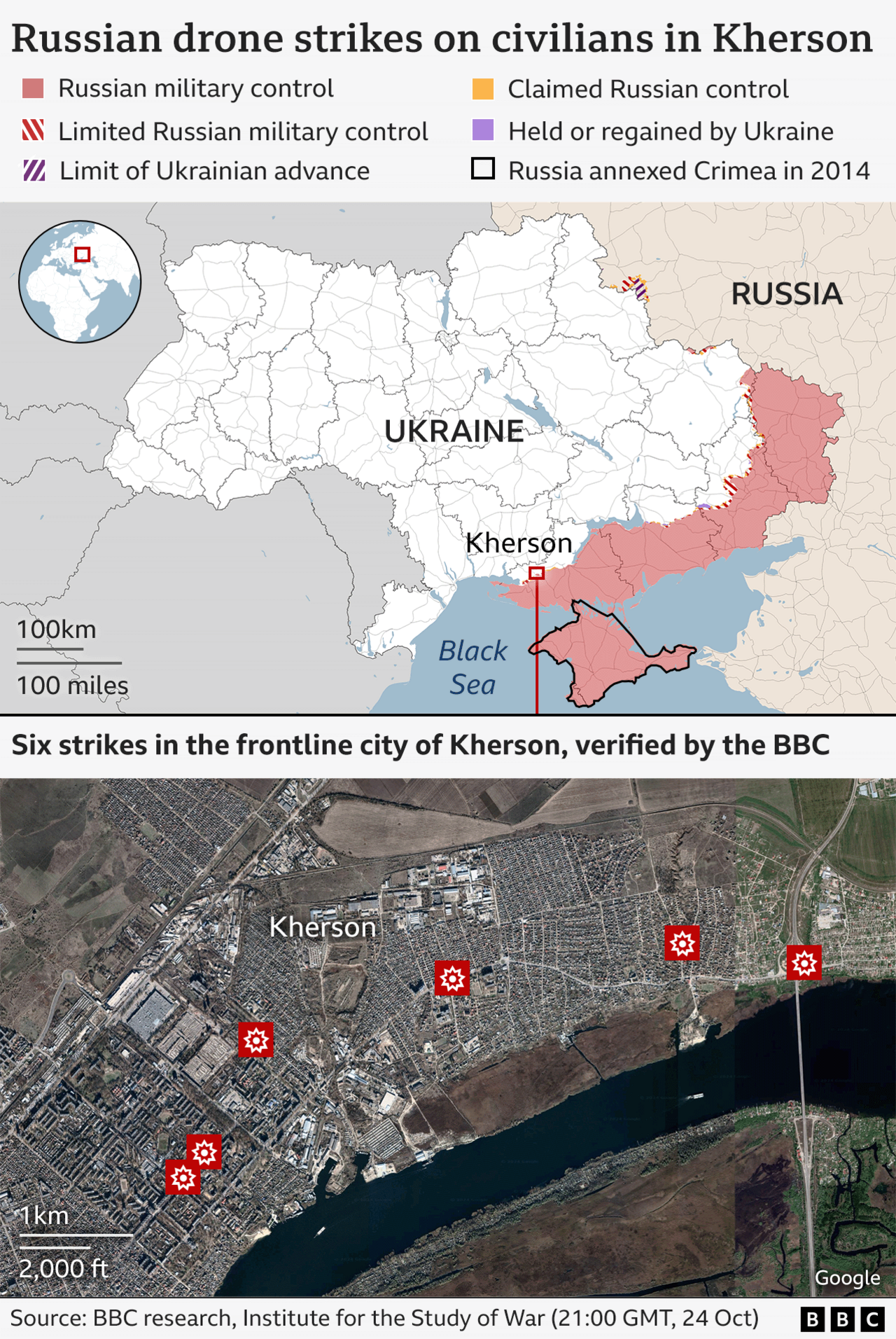

Evidence of apparent drone attacks on civilians can be seen in numerous videos shared on Ukrainian and Russian social media, six of which were examined by BBC Verify.

In each video, we see through the remote operator’s camera as they track the movements of a pedestrian or motorist in civilian clothing, often dropping grenades which sometimes appear to seriously injure or kill their target.

BBC Verify was also able to identify a Telegram channel which has the earliest public copies yet seen of five of the six videos analysed.

They were each posted with goading and threats to the Ukrainian public, including claims that all vehicles were legitimate targets and that people should minimise their public movement. The injured people were also insulted, called "pigs" or in one case mocked for being a woman.

The account posting some of these drone videos also posted images of boxed and unboxed drones, and other images of equipment, thanking people for their donations.

Kherson’s military administration told the BBC that Russia has changed the type of drone it is using and the city’s electronic systems can no longer intercept a majority of them.

“You feel like you’re constantly being hunted, like someone is always looking at you, and can drop explosives at any moment. It’s the worst thing,” says Kristina Synia, who works at an aid centre just 1km (0.6 mile) from the Dnipro river.

To get to the centre without being followed by drones, we drive at a high speed, take the cover of trees while parking, and then head indoors quickly.

On a shelf behind Kristina, a small device confirms the threat outside – buzzing each time it detects a drone. It buzzed every few minutes while we were there – often detecting the presence of at least four drones.

Trauma is visible on the faces of the residents we meet, who have braved stepping out of their homes only to stock up on food. Valentyna Mykolaivna wipes her eyes, “We are in a horrible situation. When we come out, we move from one tree to another, taking cover. Every day they attack public buses, every day they drop bombs on us using drones,” she says.

Olena Kryvchun says she was narrowly missed by a drone strike on her car. Minutes before she was due to get back in her car after visiting a friend, a bomb fell through the roof above the driver’s seat, ripping through one side of the vehicle and leaving it a mangled mess of metal, plastic and glass.

The interior of Olena Kryvchun's car was ripped apart by an explosive from a drone

“If I’d been in my car, I would have died. Do I look like a military person, does my car look like a military car?” she says. She works as a cleaner and the car was essential to her work. She doesn’t have the money to fix it.

Olena says drones are more terrifying than shelling. “When we hear a shell launch from the other side of the river, we have time to react. With drones, you can easily miss their sound. They are quick, they see you and strike.”

Ben Dusing, who runs the aid centre, says drones spread even more fear than shelling, immobilising the population. “If a drone locks on you, the truth is it’s probably ‘game over’ at that point. There’s no defence against it,” he says.

In the last few months, says Oleksandr Tolokonnikov, spokesman for Kherson’s military administration, the Russian military has also begun to use drones to remotely drop mines along pedestrian, car and bus routes.

He said explosions had been caused by butterfly mines - small, anti-personnel mines which can glide to the ground and detonate later on contact - which are coated with leaves to camouflage them.

The BBC has not been able to verify the use of drones to distribute mines in Kherson.

Olena says that as winter approaches, the fear of drones will get worse. “When the leaves fall from the trees, there will be many more victims. Because if you are in the street, there’s nowhere to hide.”

How we verified the drone videos

We were able to locate the six videos we analysed, which were all filmed in the eastern side of Kherson, by identifying distinctive features in the city streets. In one case - where a drone dropped an explosive on two pedestrians, injuring one of them so badly he could not walk - this was a curve at a T-junction, which pointed to the Dniprovs'kyi district or the nearby suburb of Antonivka, rather than Kherson city centre.

Once we identified a possible location, we were able to match visible landmarks in the video to satellite images - in this case the buildings and pylons - confirming where in the city the attack took place.

To try to establish where the videos had first appeared publicly, we ran several frames from each through search engines. Often the earliest result was a particular Telegram channel, pre-dating reposts on sites such as X or Reddit by several hours.

Having the location of each attack, we were able to calculate the time of filming using the shadows and to cross-reference with weather records to find the most likely date.

Four of the videos we examined were posted on the Telegram channel the day after the likely filming, and in one example, it was posted eight hours later the same day.

Additional reporting by Imogen Anderson, Anastasiia Levchenko and Volodymyr Lozhko. Verification work by Richard Irvine-Brown