January 27 was formally designated Holocaust Memorial Day by a resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations in 2005. But how we remember the Holocaust has evolved over the decades and even now - some 80 years on - it is a story of remembrance that is still unfinished.

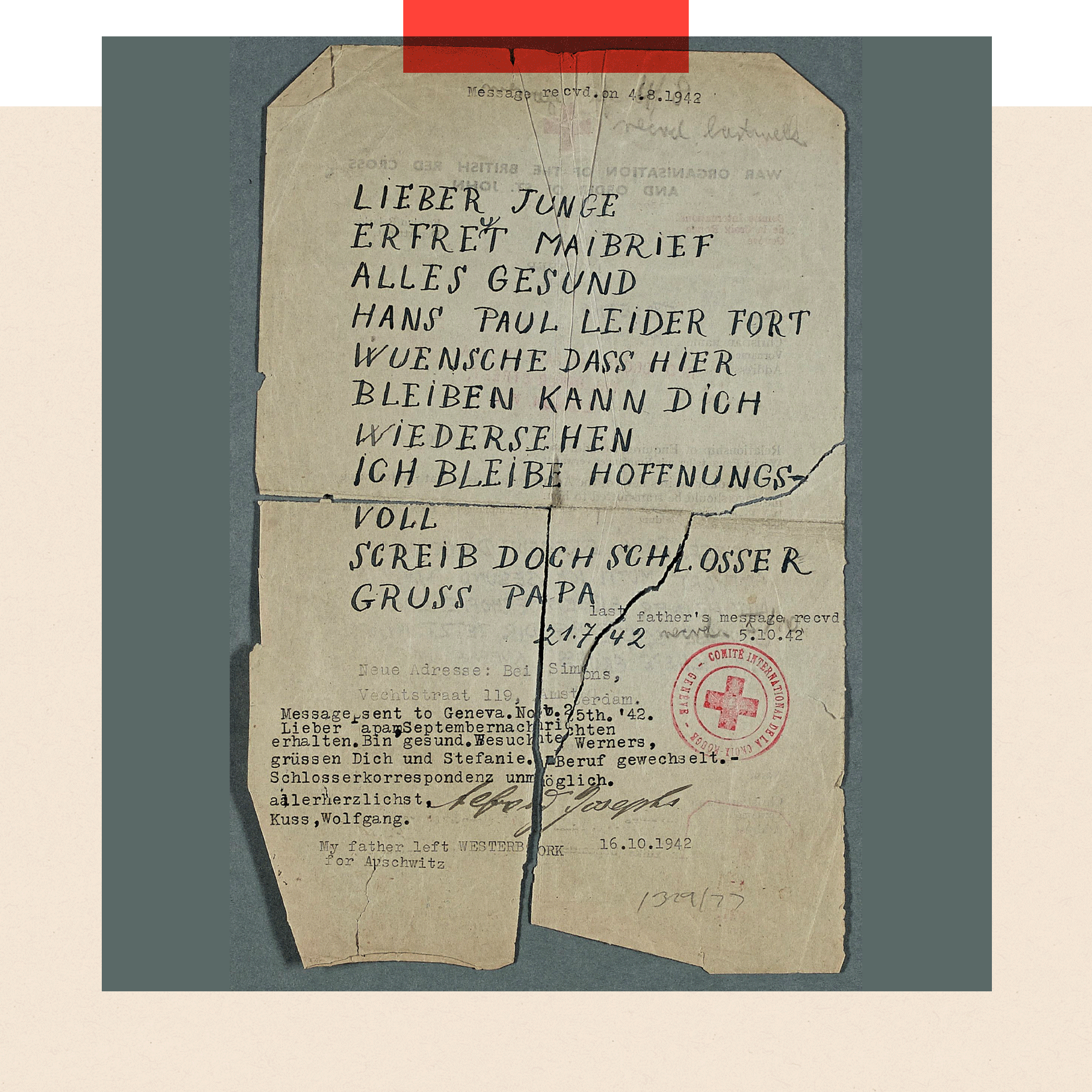

"Dear boy," the short handwritten note from 1942 begins, "I was delighted with your May message. I'm healthy. I hope that I can stay here and see you again. I remain hopeful. Please write. Greetings, your father."

The note is one of thousands of documents held by the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, one of the world's largest Holocaust archives.

The Jewish man who wrote it was called Alfred Josephs, and he was sending it to his teenage son Wolfgang, who had escaped with his mother to England. Alfred had been arrested and was being held in the Westerbork detention camp in The Netherlands.

He was still, at the time, able to pass short messages through the Red Cross.

In this letter Alfred Josephs said he was fine. It was the last message his son Wolfgang would ever receive from his father

What Alfred didn't know was that Westerbork was a camp whose inmates were to be transported to Auschwitz. Wolfgang would never hear from his father again.

By 1942 Auschwitz was the extermination camp that sits in our shared memory. Its main purpose was mass murder.

Newsreel filmed by the allies after the liberation of Europe shows German civilians being forced to visit the camps by the troops.

Auschwitz became a labour camp, having initially been used by the Germans to house Polish prisoners of war

"It was only a short walk from any German city to the nearest concentration camp," says the American voice-over. The camera catches relaxed, smartly dressed Germans laughing and chatting as they make their way.

They walk past the corpses, piles of emaciated men and women, men and women who may even have been their neighbours, colleagues, friends in the past. The camera that had captured their relaxed, easy smiles before they entered the camps now records their horror.

Shock registers on their faces. Some weep. Others shake their heads, fold handkerchiefs to their faces and look away.

Auschwitz was liberated by Soviet troops on 27 January 1945. Posterity honours the memory of the victims each year on the anniversary

Post-war Europe looked at this horror and acknowledged the depth of the suffering. But how did post-war Europe make sense of the perpetrators?

When we talk of industrialised killing, we don't just mean the scale of it, vast though it was. We also mean the sophistication of its organisation: the division of labour, the allocation of specialist tasks, the efficient marshalling of resources, the meticulous planning that was needed to keep the wheels of the killing machine turning.

Those same newsreels show well-fed Nazi guards, both men and women, now in allied custody.

What was the nature of the moral collapse that turned this horror into a normality for the Nazis who ran these camps, a normality in which mass murder became, for them, all in a day's work?

This is a question that has been touched on many times before but even now, some 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz, has yet to be fully comprehended.

Turning away from a hard question

For years after the war, public attention turned away from this question, but also away from trying to understand the question of what had happened more broadly.

Though some Nazi war criminals were prosecuted, the new priority, in a Europe divided by the Cold War, was to turn West Germany into a democratic ally.

The Holocaust almost disappeared from popular memory, in much of the Western world. The post-war public wanted to turn the page on the war. In popular culture, in Britain, for example, the appetite was for stories that could be celebrated and cheered.

"The culture of memory of the Second World War was still emphasising heroism," says Dr Toby Simpson, the director of the Wiener Holocaust Library. "There was an emphasis on the Normandy landings, for example.

"And in the stories that the survivors wanted to tell there was very little heroism to be found in a story where they've been stripped of their humanity, agency, their choice. They'd been turned into a non-person."

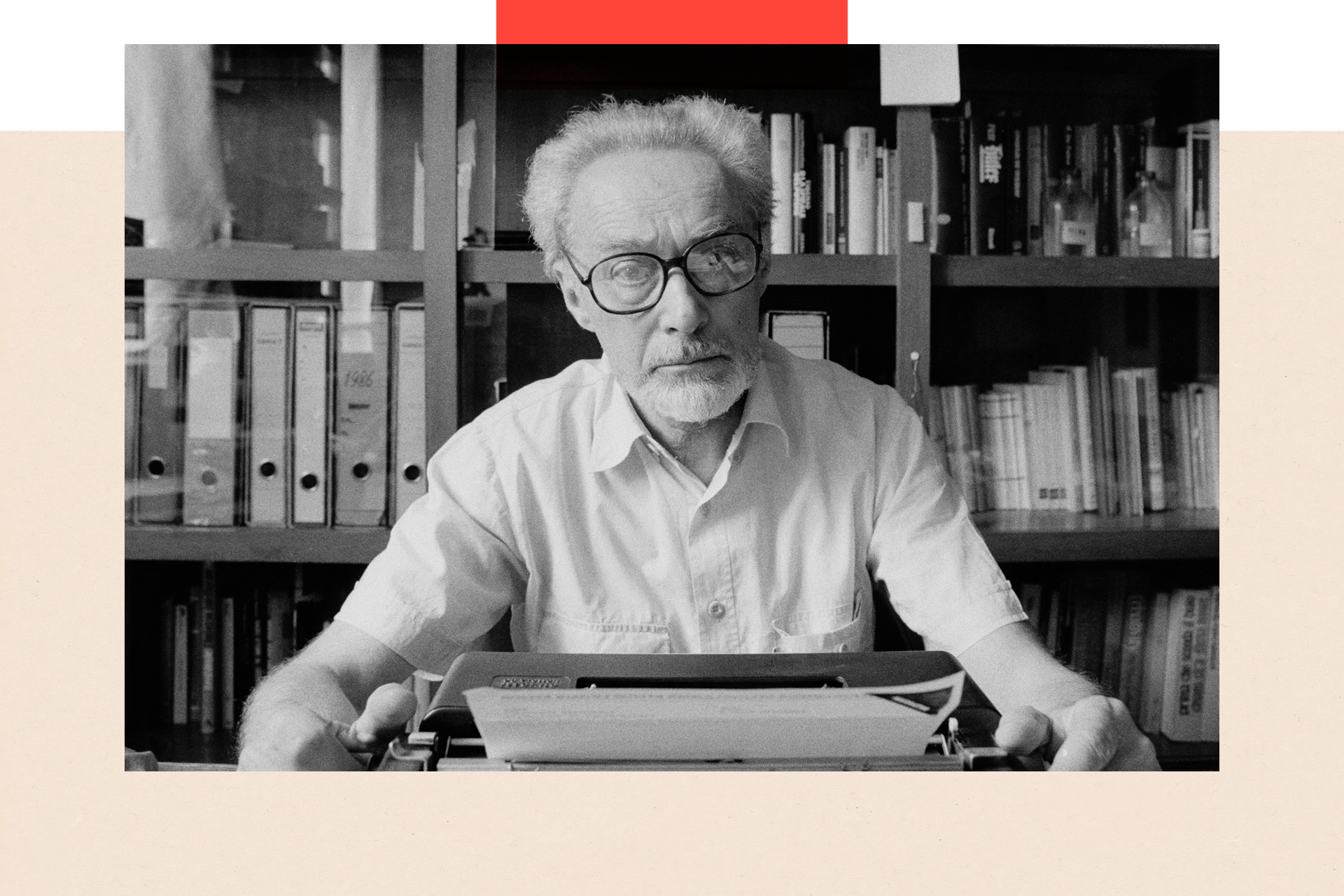

Primo Levi initially struggled to find a publisher for his book, If This is a Man

The Italian survivor, Primo Levi, wrote his Auschwitz memoir If This Is A Man immediately after the war. He had been one of a few thousand still at Auschwitz when Soviet troops arrived on 27 January 1945.

Most prisoners had been forced to march west, towards Germany, in freezing winter weather. Already weakened by camp conditions, many died on the way in what came to be known as the Death Marches. Levi was too sick and Soviet troops found him close to death in the camp infirmary.

'Not forgiving and not forgetting'

Today, If This is a Man is regarded as a masterpiece of survivor testimony and one of the most important memoirs of the entire era. But in 1947, Primo Levi found it hard to find a publisher, even in his native Italy.

Finally, a small independent publisher in Turin published it in a print run of 2,500. It sold 1,500 copies then disappeared. For publishers, and for the public, it was still too soon. Few, it seemed, wanted to look.

"Primo Levi didn't sell because the time wasn't right and because he was too great a writer to give a heroic answer. His answer is greater than heroism," says Jay Winter, professor of history Emeritus at Yale University. Many of Prof Winter's mother's family were killed in the Holocaust.

He adds: "A lot of people turned Primo Levi into a saint but all you have to do is to read the poem at the beginning of If This is a Man to see that he is not forgiving anybody - he is not forgiving and not forgetting."

"Primo Levi didn't sell because the time wasn't right and because he was too great a writer to give a heroic answer," says Professor Jay Winter

"There was Holocaust memorialisation in the 1950s," says Prof David Feldman at Birkbeck University in London, "but it was something that was done by Jews themselves, in small fragmented groups.

"These were occasions of mourning more than memorialisation. The idea that we have now, of memorialisation, that somehow there are lessons to be drawn from the Holocaust, was not commonplace then".

According to Prof Winter: "The countries that were reconstructing… needed a myth of resistance, of heroic armed conflict against the Nazis or Italian fascists." That myth of resistance "had no place for concentration camp inmates".

A cultural shift in attitudes

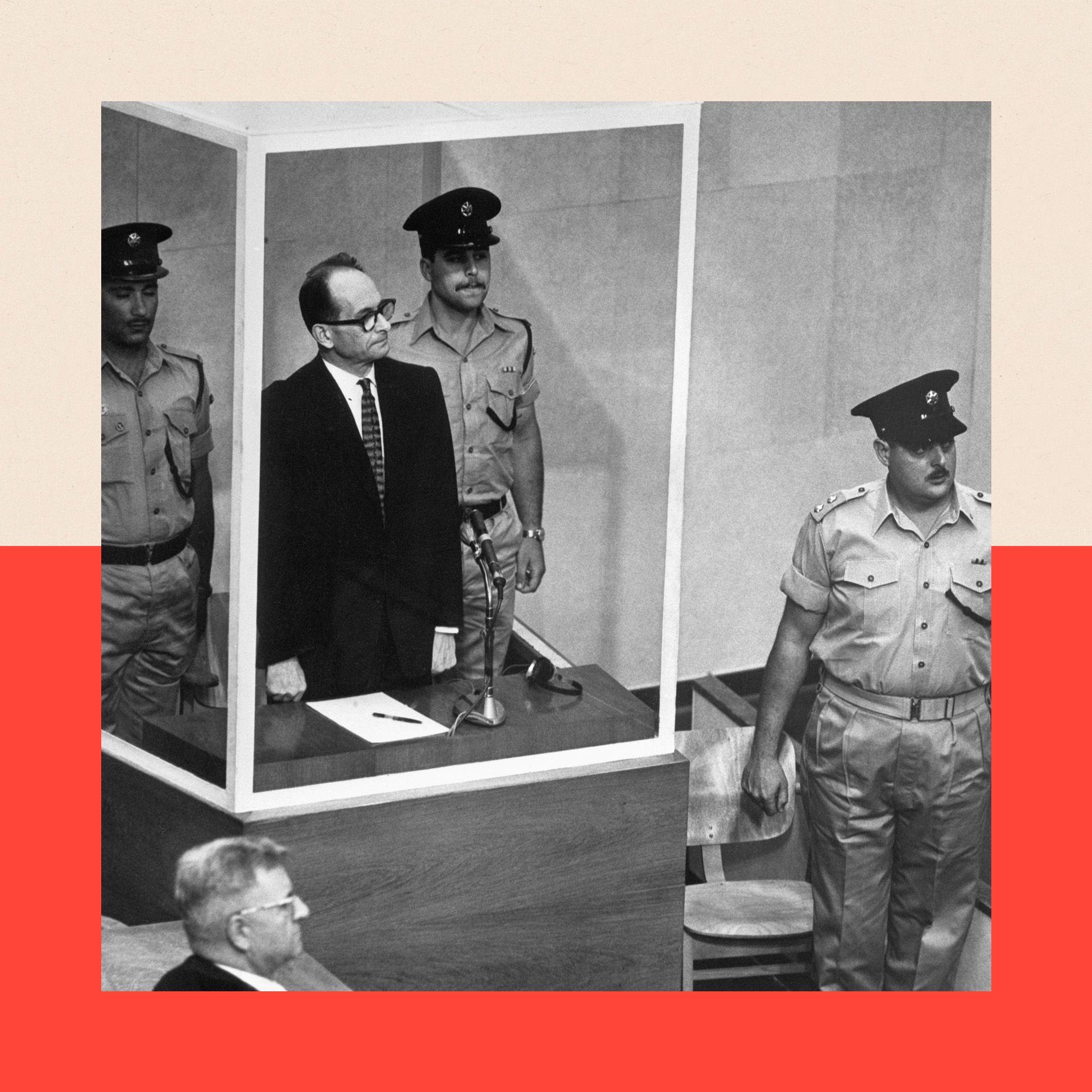

Only in the 1960s did popular interest return. When Israeli agents captured Adolf Eichmann, a key figure in the extermination campaign, they put him on trial in Jerusalem, and televised it. Now, Holocaust memorialisation began to reach the wider public.

Through the Eichmann trial, the new mass medium of television brought survivors' testimony into the living rooms of the western world.

It coincided, too, with a cultural shift in public attitudes to war. A generation born in the aftermath of World War Two were coming of age in the 1960s.

Benjamin Britten's War Requiem incorporated the words of the World War One poet Wilfred Owen - whose poetry had also faded from popular consciousness - to a new generation. Anti-war sentiment was fuelled further by the US involvement in Vietnam.

The televising of Adolf Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem helped spread Holocaust memorialisation to the wider public

"I would say the Eichmann trial also brought perpetrators into people's living rooms," says Prof Feldman. "Survivors' testimony and the emphasis on survivors being central to Holocaust memorialisation came later. It developed slowly in the 1960s. By the 1990s it was well established."

The Holocaust story - at last - took its place in our collective consciousness.

From the 1960s onwards, Levi's memoir found a global readership. Anne Frank's father Otto had also struggled, in the early post-war period, to find a publisher for his daughter's diary. To date it has sold an estimated 30 million copies.

What became of Alfred Josephs

As for Wolfgang Josephs, as late as August 1946, he was still hoping against hope that he might find his father alive. He received a typewritten note from the British Red Cross. It informed him, with regret, that Red Cross officials in Europe had searched the lists of survivors, and his father's name was not among them.

Wolfgang anglicised his name to Peter Johnson and settled in the UK, at a time when few in the western world wanted to hear the stories of those who had witnessed, or survived, the Holocaust. He donated his family papers to the Wiener Holocaust Library, which remains a vast repository of evidence of the darkest period in Europe's history.

Now, 80 years on, there are so few survivors left that soon the duty to remember will pass to posterity.

"I think remembering the Holocaust is even more important now," says Dr Simpson, "because it happened at such a scale, and with such an intensity of hatred, that [there is still] the need to understand, to explain this continent-wide event in which six million Jews were murdered." And so too is there still a need to fully comprehend how to make sense of the perpetrators - and the nature of the moral collapse that enabled this to take place.

As Primo Levi wrote: "The injury cannot be healed. It extends through time."

Correction 30 January 2025: This article originally described Auschwitz as being used to house Polish prisoners of war and that it later became a labour camp. However Auschwitz was always a concentration camp and so we have removed this line from the story.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.

Related topics

- Published27 January

- Published26 January