Fall in mental health calls saves police time - Met

Police now only attend mental health incidents if a person is at risk of serious harm

- Published

Joe West and Jack King - two Metropolitan Police officers - are just a couple of hours into their Friday shift on the Bromley response unit when a call comes over the radio: a boy has just been chased through Beckenham by a group of teenagers, one of whom has a knife.

After a search of a nearby park, a boy is arrested and the knife is seized.

It is the kind of call the officers believe they should be focusing on - and the kind they say they can now respond to more quickly - since the Met's Right Care Right Person (RCRP) initiative was launched alongside the NHS in November 2023.

The changes aim to reduce the number of mental health-related incidents police attend, and mean the force only responds if a person is at risk of serious harm.

Six months on from the launch, the Met says it is responding to about 6,000 fewer calls every month, freeing up roughly 34,000 hours of officers' time to tackle crime.

Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley told BBC London that since RCRP was rolled out, the force was now attending about 500 more robberies a month.

"It really has made a massive difference to us in how we respond to crime," PC West said.

He explained he previously spent "entire shifts" sitting in a hospital emergency department waiting with someone struggling with their mental health to receive care, but estimated the new approach has reduced such call-outs by up to 70%.

"It's giving us that time to actually go out and actively hunt for burglary suspects, and look for people that are involved in stealing cars, and bring positive results back to the public," he added.

PC Joe West, right, says his response unit is now able to focus on crimes such as burglary and car theft since RCRP was introduced

As part of the scheme, a new 24-hour helpline has also been set up for officers to call for advice before detaining someone under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act, which PC West believes is better for patients.

"People that are suffering from mental health issues don't want to see police," he said.

"I think that's something that has been has been abundantly clear ever since I joined the job.

"Sometimes, you know, the uniform can look quite intimidating, and we may turn up with a few of us, and we completely understand that looks very intimidating."

PC West says he previously spent "entire shifts" sitting in A&E after attending mental health incidents

PC West said being able to call the helpline had given him greater confidence in the decision-making around whether a person needs to be sectioned.

During such a call, there is a discussion about issues like the medication the person is taking and whether they are engaging with mental health services, before advice is given on the best option for care.

If a decision is made that the person does not need to be sectioned, officers are given options of a "safe" alternative place they can be taken to - perhaps to a friend or family member - and arrangements for further checks from the mental health team.

PC West said before RCRP, officers' time would also be spent waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

While the initiative has been received positively within the Met, what impact is it having on patient care?

When RCRP was first announced by the Met Police Commissioner in spring 2023, there was general agreement that police were often not the best people to respond to mental health incidents.

But some in the NHS privately worried it was being brought in too quickly and charities raised concerns about whether vulnerable people could fall through the net.

The scheme, initially supposed to launch that September, was then delayed by two months.

When the rollout was discussed by London's police and crime committee at City Hall in February this year, it was clear those concerns remained.

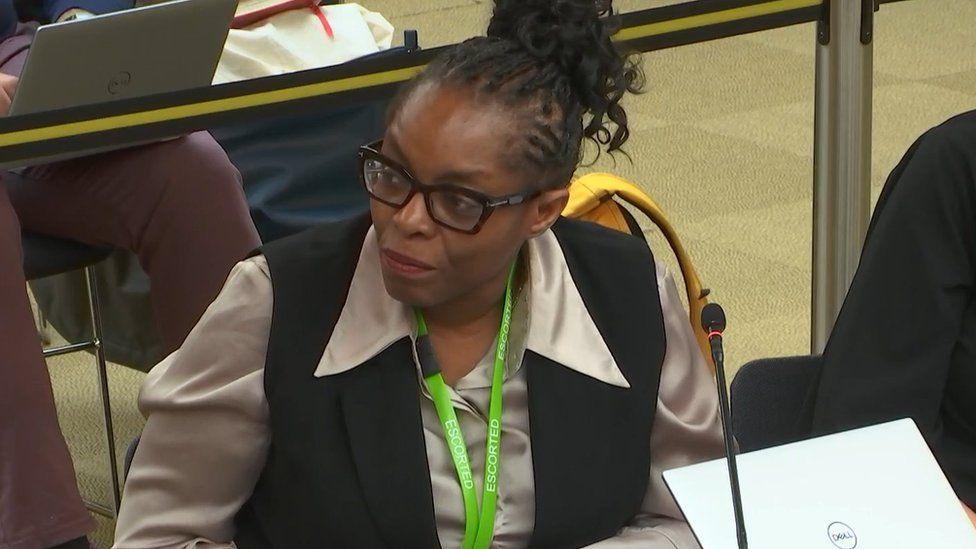

Dr Lade Smith told the London Assembly that in some cases A&E staff were going to a person’s house to look for them because police would not attend

Dr Lade Smith, president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, told the committee there were increasing reports of police refusing to attend when vulnerable people go missing from hospitals or mental health units, and in some cases A&E staff were having to go to a person’s house and look for them.

She told BBC London basing the success of the scheme on police statistics overlooked the potential "negative impact" on mental health, social care and ambulance services, which often do not have the same legal powers as police to transfer people to certain services.

Dr Smith added: "It's not necessarily people getting the right care by the right person, sometimes it's people simply getting less care because they're not getting support."

However, Sir Mark said the force had "a strong line of communication between our teams day to day, and the health service teams".

He said they had not seen any evidence of "anybody slipping through any cracks".

“We will always turn up to save lives, that was never in doubt. But if it's simply a mental health crisis then I think we'd all expect, if it was a relative of ours, for that to be a medical professional," he added.

The Met says it is now responding to about 6,000 fewer calls for mental health incidents every month

Despite a reduction in call-outs for such incidents, when BBC London joined the officers on shift it was clear most of the calls coming in were still mental health related, and all required a police response.

A man at a railway station was in a mental health crisis. A woman was threatening to harm her child and herself. An autistic child had jumped out of a moving car and run away. In each case, officers rushed to the scene.

Fortunately, the first call turned out to be a false alarm, but police discovered the woman was a victim of domestic violence and officers were sent to support her.

The runaway boy was found safe and well in the toilets of a nearby takeaway, and PC West gently coaxed him to come out so he could be reunited with his family.

The officer said "in a dream world" there would be more mental health resources and more hospital beds, but he believed RCRP is a better approach.

"Ultimately, if somebody is suffering, the less time they spend with the police is the best result, because I personally wouldn't want to be with a police officer if I was in the place they were in," he said.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published1 November 2023

- Published8 February 2024