Even before the LA fires, Californians fled for 'climate havens'

More than 150,000 people were forced to evacuate due to the recent fires in LA

- Published

Christina Welch still remembers what the sky looked like the day a wildfire came within 2 miles (3.2 km) of her Santa Rosa, California, home.

It was the Tubbs fire of 2017, the most destructive in California history at the time. Ms Welch's neighbour woke her in the morning, and told her to grab her belongings and get out. When Ms Welch opened the door, ashes were falling from the sky and smoke filled the air.

Then, in 2019, the Kincade wildfire forced her parents to evacuate for five days.

It was the final push for Ms Welch. After advice from a friend, she packed her belongings and drove across the country to her new hometown: Duluth, Minnesota.

"It was just the culmination of all of it," the 42-year-old said. "There's only so many times that I was going to go through every fall of worrying about what is going to set on fire, if I was going to lose a house."

Ms Welch is one of several people who has left California in recent years because of the frequency of extreme weather, even before the most destructive wildfires in Los Angeles history killed 28 people this month.

Climate change has made the grasses and shrubs that are fuelling the Los Angeles fires more vulnerable to burning, scientists say.

California is naturally prone to fires, but scientists believe that a warming world is increasing the conditions conducive to longer fire seasons and larger burned areas in the western US.

Just this week, a new, fast-moving wildfire broke out in Los Angeles County, north-west of the city, forcing tens of thousands of people to evacuate a region already reeling from destruction. Trump plans to visit Southern California on Friday to witness the devastation from the blazes.

Climate experts say so far, they have not seen mass migration from the state because of extreme weather or wildfires - and it's difficult to estimate the number of people who have left for that reason.

But scientists and demographic experts say that as climate change leads to weather events becoming more extreme and unpredictable, the number of people leaving the state could rise, leaving some unprepared cities with the task of welcoming new residents.

"There could be this wave of new folks saying, 'You know what? California is just not going to work out for me because this is the third time in five years that I've had to close my doors because of the extreme soot and smoke,'" said University of Michigan data science professor Derek Van Berkel.

"We have to start preparing for those eventualities, because they're going to become more frequent and more extreme."

Leaving California for 'climate havens'

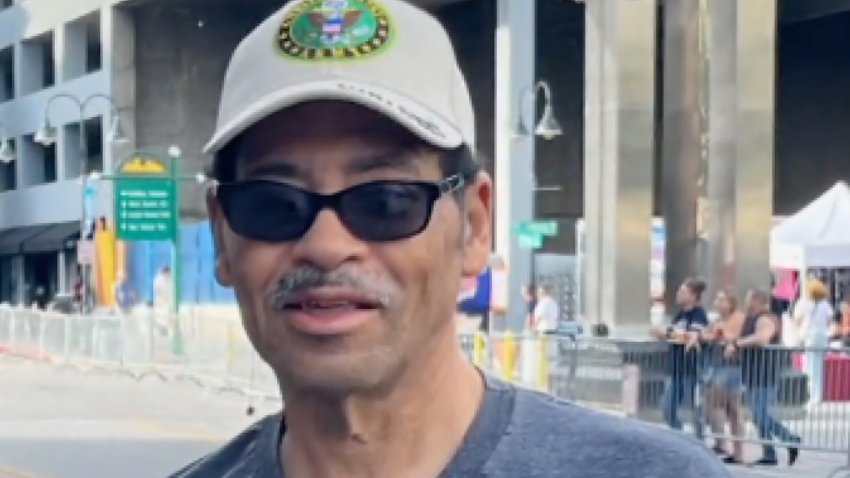

Christina Welch moved to Duluth for several years after she and her family were evacuated from multiple wildfires in California

A number of climate-related factors may push Californians to leave home over the next decade. Scientists believe that a warming world is increasing the conditions that are conducive to wildland fire.

From 2020 to 2023, wildfires destroyed more than 15,000 structures in California, according to CalFire. At least 12,000 structures have been lost in the Los Angeles wildfires that broke out at the start of this year.

The state faces other impacts from climate change as well, including flooding. Sea level rise could put half a million California residents in areas prone to flooding by 2100, according to the state attorney general's office.

As extreme weather has become more frequent, home insurance rates in the state also have continued to rise. More than 100,000 California residents have lost their home insurance since 2019, according to a San Francisco Chronicle analysis.

LA fires: How four days of devastation unfolded

Data suggests that climate migration is, so far, more of a local phenomenon, with some moving inland within their home state or even seeking higher ground in their own city to avoid flooding, said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications with First Street, which conducts climate risk modeling.

But, he said, in recent years, a smaller number of people have begun to flock to cities outside of California that advertise themselves as potential "climate havens".

The term emerged in the media after climate adaptation researcher Jesse Keenan published research about a handful of cities people were moving to because of their lower risk for extreme climate events, places Mr Keenan calls "receiving zones".

One of them was Duluth, Minnesota, a former industrial city, home to about 90,000 people, a population that has grown slowly since 2020 after years of stagnation.

One of the draws of the town is its proximity to the Great Lakes, the series of lakes that comprises the largest freshwater body in the world. Around 10% of the US and 30% of Canada relies on the lakes for drinking water.

"In a scenario where resources have become scarce, this is a tremendous asset," Mr Van Berkel said.

The Great Lakes water supply lured Jamie Beck Alexander and her family to Duluth. Alarmed by three consecutive, destructive wildfire seasons in California, Ms Alexander, her husband and two young children piled into a camper van and drove across the country to Minnesota in 2020.

Ms Alexander has found similarities between the small, progressive city and their old city of San Francisco.

"There's a real depth of connection between people, and deep rootedness, things that I think are important for climate resilience," she said.

Ms Welch ignored her friends who thought she was crazy to move to a city known for its record-breaking snowfall and icy conditions, with an average 106 days a year of sub-freezing temperatures. The crisp, pretty city on a hill has become her own, she said.

"There's a lot of people here who love where they live and want to protect it," Ms Welch said of Duluth.

Day two of LA fires: Inferno skies and charred homes

Preparing for climate migration

Though some cities have embraced their designation as climate havens, it remains a challenge for smaller local governments to find the resources to plan for new residents and climate resilience, said Mr Van Berkel.

Mr Van Berkel works with Duluth and other cities in the Great Lakes area on climate change planning, including welcoming new residents moving because of climate change.

The city of Duluth declined to respond to the BBC's request for comment on how it was preparing to potentially welcome climate migrants.

For now, Mr Porter said, the Great Lakes region and other "climate haven" cities aren't seeing high levels of migration. But if that changed, many would not be ready, he said.

"It would take a huge investment in the local communities... for those communities to be able to take on the kind of population that some of the climate migration literature indicates," Mr Porter said.

In the city of Duluth, for instance, housing availability can be an issue, Ms Alexander said. She said that although the city has space to create new housing, it does not currently have enough new developments for a growing population. As a result, in the years since she moved there, she said, housing prices have risen.

And any new housing and other developments also need to be made with climate change in mind, Mr Van Berkel said.

"We don't want to make missteps that could be very costly with our infrastructure when we have climate change rearing its ugly head," he said.

Are 'climate havens' a myth?

In 2024, a Category 4 Hurricane destroyed over 2,000 homes and businesses in Kelsey Lahr's climate haven of Asheville, North Carolina.

She moved there in 2020, drawn to the city's warm climate, restaurant and music scene, after a series of devastating wildfire seasons and mudslides near her town of Santa Barbara, California.

Before moving, Ms Lahr researched extensively the most climate-resilient places to live, with Asheville ranking near the top because of its milder temperatures and inland location, shielding it from flooding.

But last year, Hurricane Helene ploughed through western North Carolina, killing over 100 people in the state and decimating Ms Lahr's new hometown of Asheville. Many were left without power for nearly 20 days and without potable drinking water for over a month.

"Clearly southern Appalachia is not the 'climate haven' that it was built up to be," Ms Lahr said.

Ms Lahr feels safer from wildfires and other climate disasters in her new home of Asheville, North Carolina

In Duluth, Ms Alexander said her family also learned quickly that they could not run away from climate change.

During their first summer, the town was hit with the same smoke and poor air quality that drove them away from California - this time from Canadian wildfires.

"It was like, this really profound joke that the universe played on me," she said. "Unless we address the root cause [of climate change], we're always going to feel like we need to pick up and move."

Still, Ms Alexander does not regret her family's trek to Duluth. Neither does Ms Lahr regret moving to Asheville.

Though Ms Lahr often misses the ancient forests of Yosemite National Park in California, where she would spend her summers working as a park ranger, a future that may bring more climate disasters requires sacrifices, she said.

"I sort of increasingly think that climate havens are a myth," she said. "Everybody has to assess the risk where they live and go from there."

Related topics

- Published17 January

- Published15 January

- Published12 January