The journey that helped save Nigeria's art for the nation

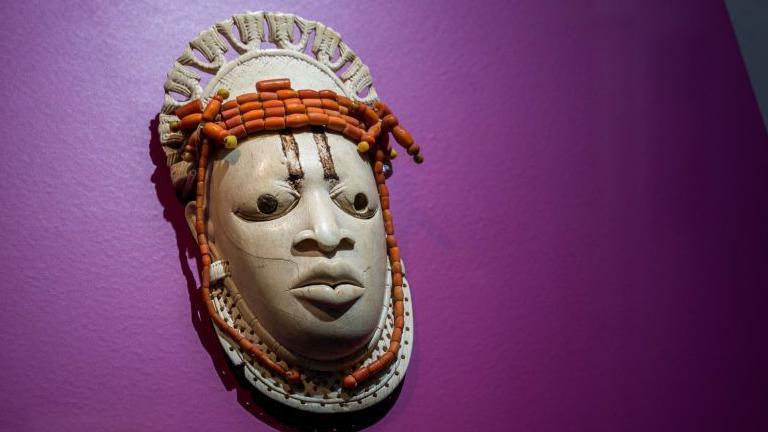

Items similar to this ivory mask were collected in the 1960s by Americans Charlie Cushman and Herbert Cole for the Nigerian National Museum

- Published

The Nigerian National Museum in Lagos sits in the city like a respected but unloved relative - it somehow exudes importance but remains largely unvisited.

This is perhaps because the concept of a museum is based on a colonial idea – stuffing cabinets full of exoticised objects removed from the context that gave them any meaning.

Olugbile Holloway, who was appointed earlier this year to head the commission that runs the National Museum, is keen to change this - he wants to take the artefacts on the road and get them seen back where they once belonged.

“How organically African [is this concept of a museum] or has this ideology kind of been superimposed on us?” he asked me.

“Maybe the conventional model of a nice building with artefacts and lights and write-ups, maybe that isn’t what’s going to work in this part of the world?”

Established in 1957 – three years before independence - the museum houses objects from across the country, including Ife bronze and terracotta heads, Benin brass plaques and ivories, and Ibibio masks and costumes.

But there is also an irony – Mr Holloway's job would not exist if the antiquities department, set up by the colonial government, had not got people to go around the country to collect the pieces that ended up in the museum.

Some may have otherwise been stolen by Western visitors with less scruples to be sold on the lucrative European and American artefacts market. While others could have been destroyed by zealous Nigerian Christians convinced that they were the devil’s work.

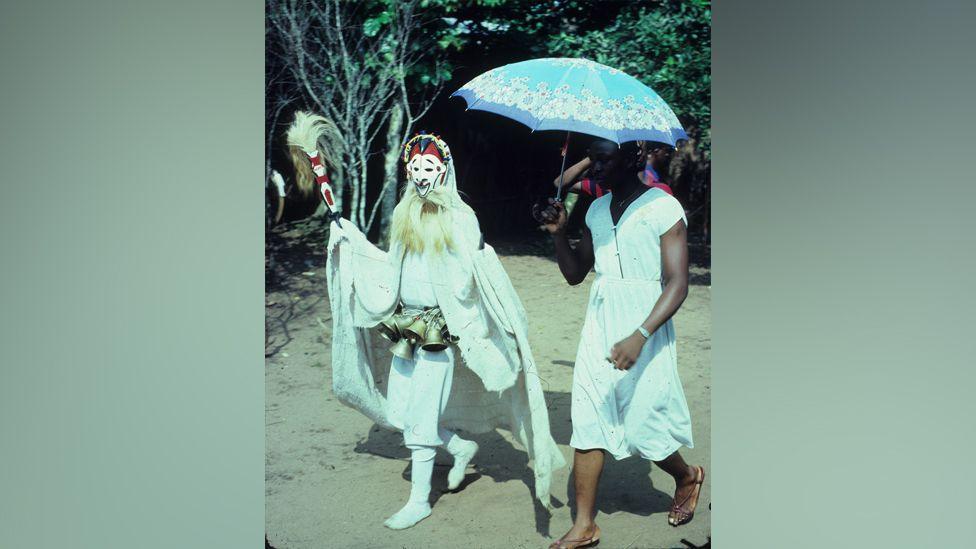

Masks, like this one pictured by Herbert Cole in 1967, remain a significant part of many ceremonies in Nigeria

In 1967, an unlikely American duo of Charlie Cushman, a hitchhiker, and Herbert “Skip” Cole, a postgraduate student, were sent around the country by the antiquities department, to gather up some of the heritage.

“It was an incredible opportunity to spend - what was it, two weeks? - to venture into small enclaves and villages in south-eastern Nigeria,” Mr Cushman, now 90, told me.

At that time, significant cultural artefacts were kept in traditional shrines, palaces and sometimes caves. They were often central to the area's traditional religions.

Household heads and shrine priests were responsible for maintaining and protecting these items.

“What I found particularly interesting is that many people in the villages seemed very willing to part with masks and objects that had been in their families for a long time,” 89-year-old Mr Cole told me.

“I was able to buy masks for two or three dollars. They would be worth hundreds in Europe at the time.

“Its monetary value wasn’t important in Igbo villages.

"They used the objects for ceremonies, for entertainment, for commemorating ancestors and nature spirits... which is probably why they were able to sell things inexpensively when they decided that they were no longer useful to them.”

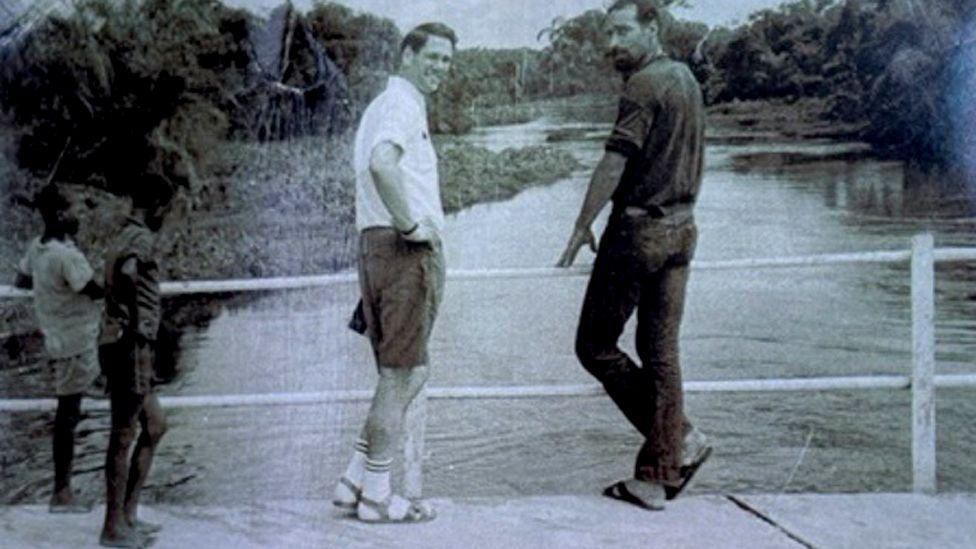

The objects that Herbert Cole (L) and Charlie Cushman (R) gathered in south-east Nigeria remain in the National Museum's archive

Mr Cushman kept detailed journals of his experiences as they travelled together in a VW minibus and on foot to retrieve these artworks, including ceremonies they observed and people they met – and those handwritten notebooks have survived more than 50 years.

I was especially fascinated by their efforts to persuade Christian converts not to destroy artefacts, which they considered pagan and evil.

The diaries describe meeting a Mr Akazi, a school headmaster and “self-appointed crusader of God” who had burnt some ancestral figures.

“They are evil and remain as crutches to the people. Only with their destruction can we rid the people of these monstrous influences,” Mr Akazi is quoted as saying.

Mr Cole tried his best to explain.

“We are here to try and preserve these art objects for future generations. Rather than destroy them, could we not have them sent to the Lagos Museum where they will accomplish both of our purposes? For you, they will no longer be here to serve as obstructions to Christianity, and for us, they will be preserved.”

It seems that the headmaster was persuaded to hand them over, but did not see their cultural value.

“You see for me there are too many emotional ties connected with these hideous manifestations of Satan. Perhaps for you, these things are art, but they can never be so for me,” Mr Akazi said.

Reading those excerpts reminded me of the times I have accompanied compatriots, who were visiting me in London, to the British Museum to see some of the Nigerian artwork on display, mostly looted from our country.

Some of my guests, who were committed Christians, refused to take photographs of themselves standing with any of the objects, concerned that they might be fraternising with demonic items. We laughed about it, but they were serious.

For some, Igbo objects like these in the British Museum are perceived as being manifestations of Satan

Mr Cushman and Mr Cole’s mission originated from an assignment by Kenneth C Murray, a British colonial art teacher, who was a key figure in Nigeria’s museum history.

Murray was invited to Nigeria at the request of Aina Onabolu, a European-trained Yoruba fine artist who convinced the colonial government to bring qualified art teachers from the UK to Nigerian secondary schools and teacher training institutions.

Murray believed that contemporary art education should be grounded in traditional art, but there were no collections in Nigeria available for study.

He was also concerned about the unregulated export of Nigerian items.

To address these issues, Murray and his colleagues pressured the colonial government to legislate against the exportation of artefacts and to establish museums.

This resulted in the inauguration of the Nigerian Antiquities Service in 1943, with Murray as its first director. He established Nigeria’s first museums in Esie in 1945, Jos in 1952 and Ife in 1955.

Mr Cole was studying African art at New York’s Columbia University and conducting fieldwork in Nigeria when Murray assigned him to collect artwork from south-eastern Nigeria for the newer museum in Lagos.

Other scholars and Nigerian employees of the museums were tasked with doing this elsewhere in the country.

“I collected more than 400 artworks for the museum,” Mr Cole said. “Murray came to my flat in Enugu and carted things off both to the museum in Lagos, and also to the museum in Oron.”

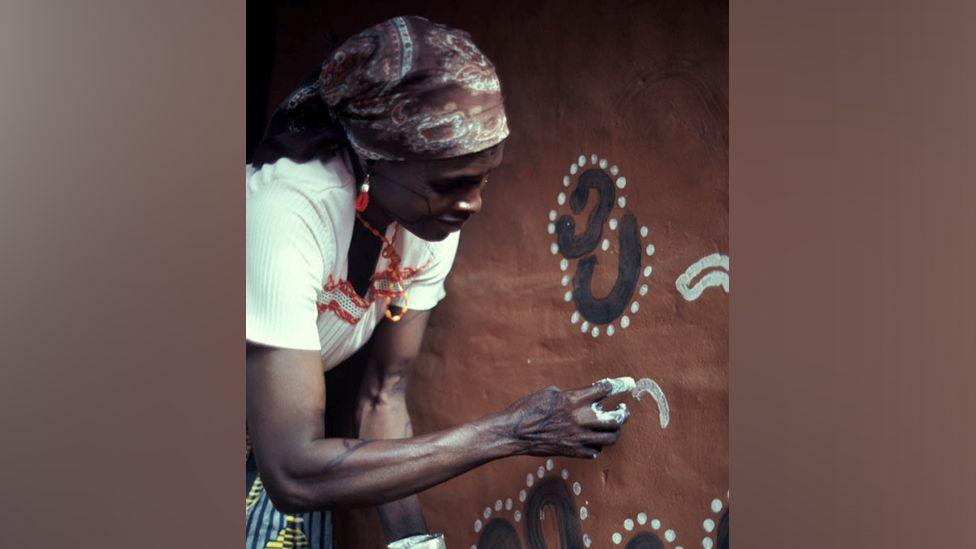

Herbert Cole photographed an artist painting the wall of a house dedicated to the Earth goddess in the Mbari style

Mr Cushman studied at Yale and Stanford Universities. He turned down the opportunity to work with investment company Merrill Lynch in New York, eventually deciding to travel the world. He ended up in Nigeria where he met Mr Cole, an old school friend, and was persuaded to join him on his mission.

The journals that Mr Cushman kept are all that survive from the trip.

Unfortunately, “Skip” lost all his own records when he was forced to flee south-east Nigeria during the civil war, which started in July 1967 when the region's leaders seceded from Nigeria and formed the nation of Biafra.

He was sad to learn later that some of the artwork he had collected for the museum in the southern town of Oron had been destroyed.

“The Nigerian army took over the museum because it was the only building around with air-conditioning so they would use artefacts as firewood to cook their food,” he said.

But much of what the two men, and others, collected survived and is now the responsibility of Mr Holloway as the head of the Nigerian Commission for Museums and Monuments.

He hopes to develop a new concept of a museum that is more appealing to, and representative of, Nigerians and Africans.

“We have about 50-something museums across the country and the vast majority are not viable, because people are not interested in going into a building that has no life.

“To the white man or to the West, what they would call an artefact to us is a sacred object… I feel that the richness in those objects would be to display them as they would originally have been used.”

More BBC stories on Nigerian artefacts:

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external