Born in the shadow of Britain's Nazi camps

Janet Pope was born on Alderney during the German Occupation of the island

- Published

In an early childhood memory, Janet Pope stands in the shadow of a house on the island of Alderney amid an "eerie silence", summoning the courage to step into the sunlight.

It was 1945, she said, and the German Occupation of the Channel Islands was drawing to a close.

Her family had just spent an arduous half-decade living treacherously close to four forced labour camps, including one taken over by the SS.

They left Alderney, said Ms Pope, with the emotional and physical scars of what they had experienced - including witnessing the brutal treatment of camp prisoners, many of whom died.

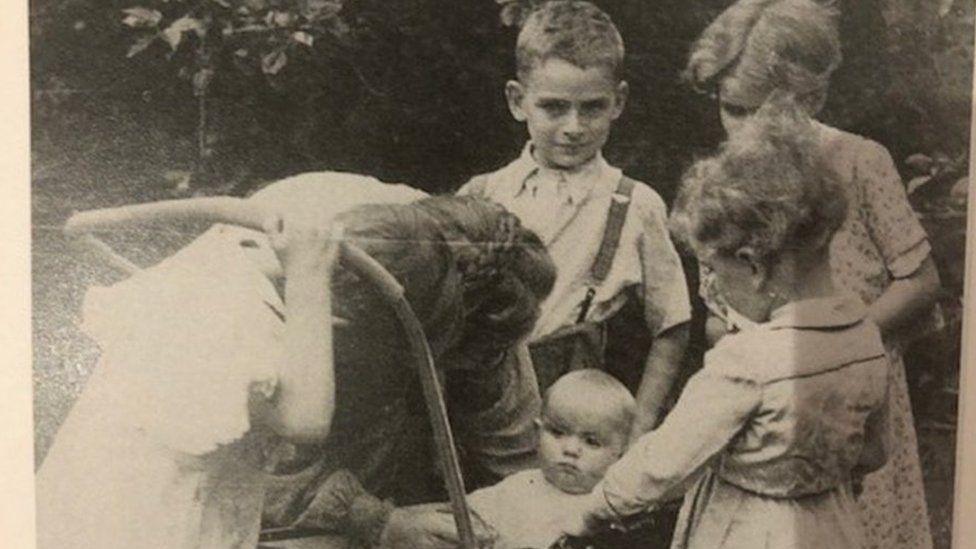

Janet Pope was born in Alderney during the occupation

Ms Pope, now 80, said: "It was a five-year chunk of living a precarious existence.

"For years and years and in lots and lots of books, they said nobody was there during the war, there was nobody to witness what happened in Alderney during the occupation.

"But we were there."

Alderney is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands, which were occupied by the Germans in 1940 as part of their advance across Europe.

By the time of this invasion, most of its 1,500 islanders had been evacuated - but not all.

Alderney-based historian Jurat Colin Partridge OBE said by July 1944, there were 16 civilians left in the island.

Ms Pope said her family, including her grandmother, was among them.

Her mother, she said, had refused to leave without their father, who had run into trouble on a fishing expedition.

Historical archives show prisoners, who came from 27 countries, were held at four camps, including the SS-run Lager Sylt, with post-war reports citing 389 people died during forced labour to build Hitler's "Atlantic Wall".

Convened by Lord Pickles, a panel of international experts has been tasked with finding an accurate figure for those who lost their lives, with findings due to be published on Wednesday.

They were also tasked with investigating why those responsible were not put on trial for war crimes in the UK.

The mark of five years of occupation can still be seen across the island

Ms Pope said her family witnessed "cruel and appalling" treatment of prisoners.

She added: "Prisoners would come down past our house on the way to the harbour where they had to work rebuilding the sea walls.

"My parents were very keen to ensure their children didn't see these prisoners and the guards taking them down to the harbour but my older sister did see.

"She said she kept thinking what on earth had they done to deserve this treatment."

Despite her parents' efforts to shield the family from the horrors on their doorstep, Ms Pope said the truth would later emerge - through their stories, as well as written and taped accounts.

Her mother would also express her anger at their "beautiful island being covered with concrete, land mines and barbed wire".

By the time Janet Pope was four the family had moved to England

Ms Pope said she often reflected on the circumstances that led to her family remaining in Alderney.

Her parents were on their way from Chichester, with their children and her grandmother, to New Zealand by boat, and had stopped off in France, when war broke out.

They were advised to make their way to the nearest British territory - and after a brief time in Jersey and Guernsey, ended up in Alderney.

After missing the evacuation in June 1940 due to her father's absence on a fishing expedition, Mrs Pope said, the family, including four children, remained in their rented house in Alderney.

"I think they gritted their teeth and just got on with staying alive."

Janet Pope said her family would see prisoners on their way to build the 6m (20ft) high anti-tank wall at Longis and other fortifications

When the Germans arrived, Ms Pope said her father told them he was an Alderney fisherman and was told by the German commandment to act as their harbour pilot.

She said at first he refused, but relented when his family was threatened with a gun, determining the course of their lives for the next five years.

Ms Pope said the Germans were strict at prohibiting contact between islanders and prisoners.

"If you were caught helping anyone basically you could be shot," she said.

"You couldn't leave."

Food was scarce, and became increasingly so as the war continued, she said.

"Basically my mother said all she was interested in was finding enough food for the children and they get on with their lives the best they could."

They survived on a bread ration from the Germans, vegetables grown by her grandmother and milk from a cow acquired by her father.

"My father would fish but he had to give most of his catch to the Germans," she said.

"I know there was no baby food, they had to find whatever they could and mince it up and hope I stayed alive."

There was no school, and when her mother was not trying to teach them to read and write "they just ran free".

"Obviously they knew if there was skull and crossbones sign or barbed wire to keep away and they were never allowed to the beach or sea."

Ms Pope was born in December 1943, without medical help and during a year in which a dysentery-type illness was spreading across the island.

After the Allied invasion of Europe the garrison's supply route was cut while Red Cross parcels started to arrive for civilians from December 1944

"Prisoners were dying every day, nobody knew what it was.

"Things got tough towards the end when there really was no food, the Germans were starving as well.

"My mother said she had great respect for the Red Cross, and she said without their food parcels we wouldn't have survived.

"Nothing seemed to grow, nothing thrived including our gardens."

The island was liberated in May 1945.

Ms Pope added: "When the English soldiers arrived they put food on the kitchen table and we had never seen such things.

"I remember my sister describing seeing and eating a slice of white bread - and we'd never seen bacon."

The family moved to Suffolk, relieved to return to normality with food, shops and medical care.

"Their health suffered hugely, we were all suffering from malnutrition in some way or another," added Ms Pope.

"Five years was a long time."

Of the inquiry into the deaths of prisoners, Ms Pope said "It will be interesting to hear other stories, other evidence about the conditions in Alderney and I look forward to hearing the results of the Pickles report."

Ms Pope, a retired teacher, said she thought the sites of the camps in Alderney should be clearly marked to remember those who lost their lives.

Follow BBC Guernsey on X (formerly Twitter), external and Facebook, external. Send your story ideas to channel.islands@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

Related internet links

- Published6 March 2024

- Published7 August 2023

- Published24 July 2023