The British island and the Nazi labour camps

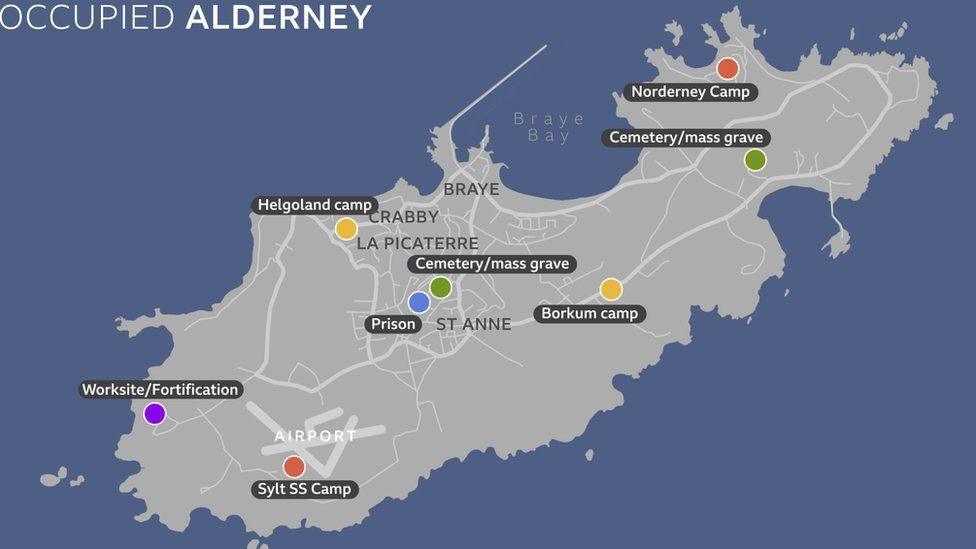

There were four Nazi camps on the island of Alderney, which measures three square miles (8 sq km)

- Published

During World War Two, a small island just 70 miles off the English coast became part of Hitler's strategy for dominance - and home to the only Nazi concentration camp on British soil.

Alderney is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands, which were occupied by the Germans in 1940.

Most of the 1,500 residents had been evacuated to the UK but a small number remained, living an often precarious existence in the shadow of forced/slave labour camps.

Historical archives show prisoners from 27 countries were held in brutal conditions, subjected to inhumane treatment at four camps, including the SS-run Lager Sylt, with an investigation after the island's liberation in 1945 finding 389 inmates died.

Many experts believe the figure is higher, while others, including some Alderney islanders, have expressed frustration at "speculation" around this horrific period in history and its impact on the island.

The UK Holocaust Memorial Foundation has tasked a panel of 11 international experts with finding an accurate figure for those who lost their lives and investigating why no UK war crime trials were held for those responsible, with findings due to be announced on Wednesday.

Lord Pickles, the UK's Holocaust envoy who ordered the review, said: "Numbers matter because the truth matters. The dead deserve the dignity of the truth; the residents of Alderney deserve accurate numbers to free them from the distortion of conspiracy theorists."

Lager Sylt was taken over by SS officers in 1943

As the Germans advanced westwards in 1940, the Channel Islands were demilitarised by the British Government because they were considered to be "of little strategic value", according to Trevor Davenport, author of Festung Alderney - a book on German defences in the island.

Unaware of the withdrawal of the military, the Germans bombed St Helier and St Peter Port on 28 June, before occupying Guernsey on 30 June, Jersey on 1 July, Alderney on 2 July and Sark on 4 July.

Over the following years, the Channel Islands were clawed into Hitler's plans to create "staging posts" to invade Britain, as well as creating the so-called "Atlantikwall' - or Atlantic Wall - to defend the coastline of Europe from Norway to the Spanish border.

There were four camps on Alderney, one of which was taken over by the SS

The Channel Islands were occupied for five years

The construction was carried out by Organisation Todt (OT), made up of largely forced foreign labourers - mostly slave workers from Russia - many of whom suffered harsh, cruel and inhumane treatment, according to historians.

In Alderney the OT labourers were housed in four camps - Lager Helgoland, Lager Norderney, Lager Borkum and Lager Sylt - named after German islands.

According to archives, Lager Sylt, near the Telegraph Tower, was taken over in March 1943 by the SS, part of the so-called death's head formation that ran concentration camps.

During that year, the number of forced labourers on the island reached more than 4,000, while there were said to be 3,200 German soldiers in the garrison.

Gary Font's father was a prisoner in Alderney

British military investigator Capt Theodore Pantcheff arrived in Alderney in 1945, shortly after the island was liberated and in a book he authored said he had interviewed more than 3,000 witnesses and potential perpetrators.

Capt Pantcheff described "exceptionally hard work", for "undernourished" prisoners whose rations were habitually diverted to the SS canteen, including digging trenches of cable in "rocky soil".

Medical care was "nominal" he said, while he also cited witness accounts of prisoners being punished, beaten, hanged and shot.

The SS Baubrigade 1 left Sylt Camp and it was closed in June 1944, said Capt Pantcheff, with the camp then destroyed "and used by the armed forces as construction material elsewhere and for firewood".

His son Andrew Pantcheff said his father had known Alderney before the war because his aunt and uncle were pre-war doctors on the island.

Mr Pantcheff said his father "made himself ill", in part due to the emotional impact of what he heard and saw on Alderney.

Andrew Pantcheff said his father was exasperated over the lack of prosecutions for what happened on Alderney

Capt Pantcheff also identified perpetrators - one of whom went to prison in Europe, said Mr Pantcheff, but not for his actions in Alderney.

"The problem here is there was a conflict but because there were no prosecutions we don't have the resolutions to it, in which case there are a lot of rumours and speculation and so on."

He said his father was "exasperated" over the lack of prosecutions: "For political reasons... someone in Whitehall somewhere made sure there weren't and I don't know why."

The inquiry has been extended to include an investigation into this lack of prosecutions within the UK.

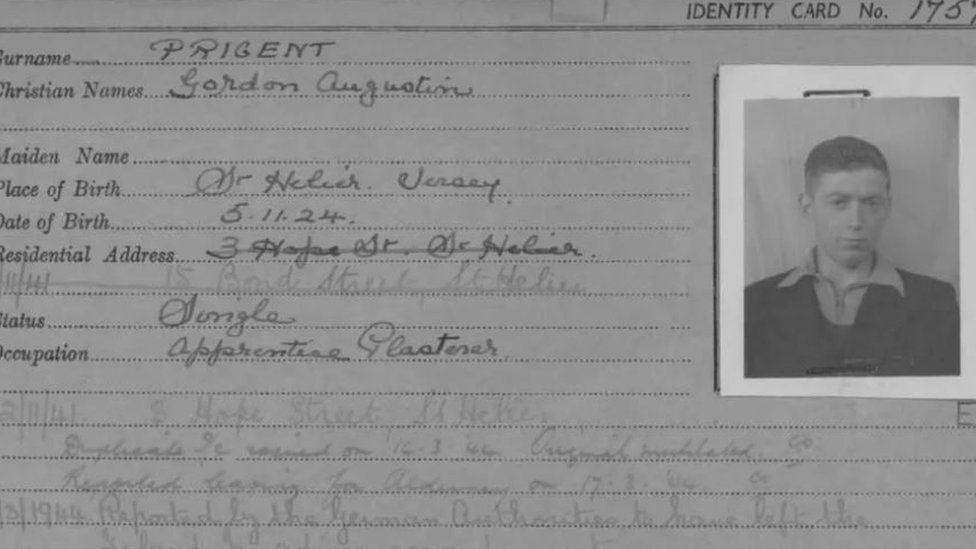

Gordon Prigent was transported to Alderney and made to work for the Germans

'He had nightmares'

Iris Prigent, 88, said her husband Gordon Prigent was 19 and living in Jersey in 1943 when the Germans demanded he work for them.

Unhappy that he should be expected to work for the people who had occupied his island, Mr Prigent refused - and the German authorities punished him severely before transporting him to Alderney.

Mr Prigent was forced to carry out a variety of jobs, on a meagre diet and with regular beatings.

Mrs Prigent said: "Some nights he had nightmares - we'd be in bed and I'd be woken up with 'Achtung, Achtung, Achtung!' [attention], and he'd be standing next to the bed, talking, you know, to a German who wasn't there."

Gordon Prigent suffered with nightmares after his experience

'Terrible things happened here'

Gary Font's father was Spanish Republican forced worker Francisco Font, who spent nine months as a slave worker in Lager Norderney.

He said as a child he and his father would visit the Hammond Memorial, overlooking Longis Common, where historians have said liberating troops found a "large burial ground".

He said he "understood" there was a possibility that many more had died "than we were told".

"I always look at Alderney... not so much a place where you would go to to enjoy the scenery - even thought it's a beautiful island - for me it's an island where so many people were persecuted and were buried and terrible things happened there.

"Fortunately the good people of Alderney have always commemorated the people who never made it back to their homes."

He said during visits to Alderney he would see a different side to his father: "I can't help but think he suffered some terrible nightmares and saw some terrible things."

Prisoners, including those at the SS-run Lager Sylt, lost their lives during the brutal occupation

As part of the inquiry, which has included field trips of panel members to Alderney and a review of archives from across the world as well as those documents kept on the island, a website was launched to "detail the Nazi occupation of Alderney".

There is ongoing debate over whether more should be done to commemorate those who lost their lives, while there has been dispute over appropriate use of the Longis Common site.

Alderney resident and Jurat Colin Partridge OBE said the inquiry, led by Lord Eric Pickles, would "draw attention to the various sites on the island and hopefully that will encourage a programme for memorialisation suitable to the size and scale of the island".

He told the BBC his expertise lay in the "construction programme" and the objective of the inquiry was to "separate evidence from speculation".

Mr Partridge said he hoped the inquiry would "open up other source of information" as a "foundation on which to build".

"I think it's important we record the names of all those who we can identify, many of them of course were forced from their home surroundings to cross Europe to come to a place they'd never heard of.

"Those who died here are forgotten in the sense their families would never have known where they died, I think we owe to them and their descendants to record those names."

Colin Partridge MBE is the only panel member from Alderney

He said various books alongside "interest in the national press" had "complicated the issue".

Mr Partridge said there had been "many sources" over the years but the "archives are incomplete".

One amateur historian from Guernsey, who asked not to be identified, criticised "speculation" about the occupation by "people with agendas".

He added: "Without a doubt, Alderney was a harsh place to be a forced worker, people lost their lives.

"But we don't want the truth twisted, the idea was that people came to Alderney to work, not to be killed as was the case in mainland Europe."

Members of the public and church leaders came together to mark Holocaust Memorial Day in January

Dr Gilly Carr, a specialist in Holocaust heritage at Cambridge University, is also a panel member.

Originally the Channel Islands representative for the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, her appointment was later rescinded after comments she made during a seminar.

Dr Carr said they used archives "from across mainland Europe, Israel, Moscow and Ukraine" to inform their findings.

She said an unprecedented amount of evidence combined with "decades of experience" had resulted in their "completion of the task".

Dr Carr added: "We calculated and worked out the number of dead and the number of labourers."

She said the number was "a lot higher" than the official figure of old.

Dr Carr said a lot of alternative theories had been "floated over the last couple of years".

She said these included "grossly-inflated numbers" unsupported by evidence.

"It's important to find out the answer to the question because this has been a subject so distorted over the last few years and highjacked by people with different agendas so it's just really important to find out the truth for their sake and in memory of the dead.

"The truth matters."

Dr Kathrin Meyer, secretary of the The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), sad: "Dealing openly and accurately with the Holocaust and the history of Nazi persecution of other groups in all its dimensions is crucial.

"We expect the results to go a long way in protecting the facts, no matter how uncomfortable they may be."

Follow BBC Guernsey on X (formerly Twitter), external and Facebook, external. Send your story ideas to channel.islands@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

More on the Channel Islands occupation

- Published7 August 2023

- Published24 July 2023

- Published28 June 2020