The dining club dedicated to disproving bad luck

Members in 1934 began their luncheon at the Savoy Hotel with a spot of indoor umbrella-opening

- Published

At the end of 1890, various London gentlemen received a letter, cordially inviting them to join a new dining club.

So far, so normal.

But this club had a novel theme - it planned to dispel the notion of omens of bad luck.

And so, in a particularly heavy-handed manner, the Thirteen Club layered superstition upon superstition in an attempt to debunk the idea that broken mirrors, spilled salt and walking under ladders could either cause, or foretell, disaster.

Archive footage shows preparation for a dinner, with an ice sculpture number 13, ladders for people to walk under and the spilling of salt

The first Thirteen Club was established in New York in 1882, and quickly became popular.

Keen not to miss out on the fun enjoyed by those across the pond, Camberwell writer and historian William Harnett Blanch got to work.

He gathered his members, and meetings were arranged for the 13th of the month (obviously) with each dinner table - set for 13 people (also obviously) - decorated with peacock feathers, thought to be unlucky because they are marked with the evil eye.

Meals were served by cross-eyed waiters "as far as possible, though the number of such individuals obtainable had been found insufficient to allow of every table in the room to be so favoured".

Dinner was announced by smashing two mirrors on the floor, and to reach their seats, guests had to follow an undertaker under a ladder before being provided with umbrellas to open indoors.

'Offensively sane'

Mr Blanch began proceedings by reading aloud letters of support from notable people - a diverse group including the attorney general, the headmaster of Harrow School - who said "superstition has been the bane of human life and I am only too glad that you should slay it" - and the president of the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour.

One person who turned down an invitation was Oscar Wilde, who declared: "I love superstitions. They are the opponent of common sense."

His reply to Blanch's letter continued: "Common sense is the enemy of romance.

"The aim of your society seems to be dreadful.

"Leave us some unreality. Don't make us too offensively sane.

"I love dining out; but with a society with so wicked an object as yours I cannot dine.

"I regret it. I am sure you will all be charming, but I could not come, though 13 is a lucky number."

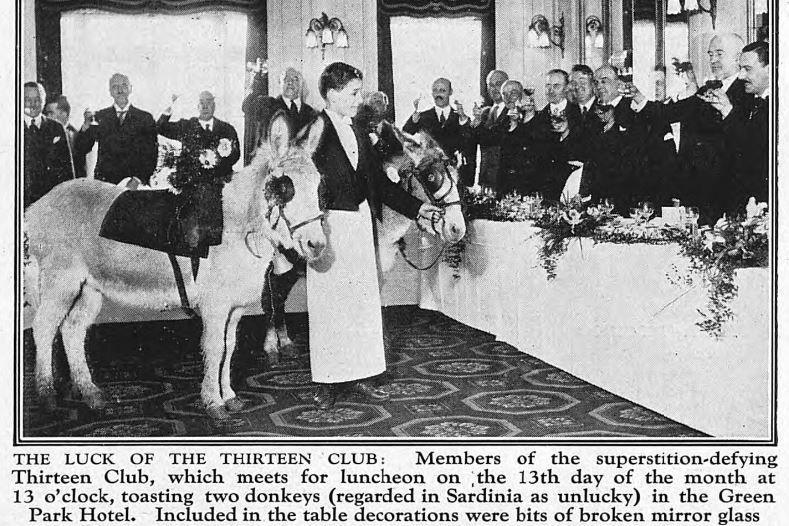

The club claimed toasting a pair of indoor donkeys was an action considered unlucky in Sardinia. There appears to be no proof of this

This "antidote to superstition" was covered by several newspapers.

A journalist asked Blanch: "Have you not a tender spot in your heart for any one, mild superstition?"

His robust reply: "Not one. I like May blossom in my house; I consider the opal a charming stone; I am happy if I see the moon through glass; I don't care a button if I upset the salt; I always walk under a ladder; superstition be hanged!"

(May blossom, or hawthorn, was considered unlucky indoors. In 1866 it was recorded in the Gentleman's Magazine that according to some, the scent of hawthorn was corpse-like, and "exactly the smell of the Great Plague of London".

Opals had a reputation for bad luck, possibly related to the belief of medieval Europeans that the opal represented an "evil eye".

Seeing the moon through glass refers to seeing a new moon in a looking glass (i.e. a mirror), meaning it appears backwards. This makes the new (waxing) moon look like a waning moon, annulling the good auspices of a new lunar cycle. Compared to the other superstitions, which seem to call the devil, the main risk of seeing a new moon through glass appears to be the prophesy that the moon-viewer would break a dish.

Spilling salt, historically an expensive commodity, was in itself bad luck. This bad luck would allow the devil, who (allegedly) sits behind the left shoulder, to get in - so throwing it in the devil's eyes prevents him.

One of the theories about walking under ladders being bad luck it that a leaning ladder forms a triangle with the ground and wall. The triangle symbolises the Holy Trinity and walking through it insults the Trinity - thus inviting in the devil, who seems to not have much else to do.)

The London events became notorious enough to be reported around the world.

A number of Australian papers including the Riverine Grazier, the Mackay Mercury and the Dubbo Dispatch all had articles about them in the 1890s and early 1900s.

The Sunday Times (a Sydney paper) went further, and conducted its own experiment by taking a pair of ladders on to the street and observing what people did.

The test was conducted outside a theatre - partly on the grounds that actors were known to be superstitious.

Some people were determined to pass beneath ladders, regardless of the suitability of hat

"Artiste Claude Bantock deliberately went out of his way to walk beneath the rungs. He seemed to glory in it!

"Andrew MacCunn, the musical director, is a 'chain' cigarette smoker — that is, he lights one 'fag' from the other — but he carefully avoided the evil influence of the ladder.

"And Miss Jessie Lonnen didn't give it a thought as she Gaby-glided under it."

(A Gaby glide was a dance move popularised by Parisienne performer Gaby Deslys).

The "accompanying photographs" as mentioned above, show passersby either ignoring the ladder or avoiding it

In half an hour, 130 people passed along the footway - and of these only 17 consciously avoided the ladder.

It was reported that "one small boy, in the uniform of a telegraph messenger, did some exercises on it" - the mind boggles - while "several other youngsters of the errand variety obviously had never heard of the superstition."

The reporter drew the conclusion that since 12 of the 17 ladder-dodgers were women, the superstition "survives principally in the gentler sex".

It seems that the denizens of Sydney were an elaborately dressed lot and the journalist had a particularly sharp eye for detail.

"One girl who practically dragged her companion from beneath the ladder's shadow was observed to be wearing a large opal pendant, showing that she didn't subscribe to all the fearsome belief of the supernatural agency of this stone.

"Another passer-by, Miss Irene Browne, dressed in bright green, which is traditionally unlucky, and another lady had a peacock's feather in her hat!"

The China Mail also suggested women were "more superstitious than men".

The writer, in not at all a sexist or patronising manner, continued: "This has been proved by careful notes. And if you come to think it out, you can prove it for yourself by remembering the odd little gestures of warding off ill-luck on the part of your feminine acquaintances."

"Careful notes" are not now considered scientific proof of sweeping gender-based generalisations.

Note the coffin-shaped decorations

The London club was still going strong in 1928, when special guests were invited to speak.

Sir Arbuthnot Lane, president of the Fellowship of Medicine, lectured on the virtues of wholemeal bread.

A "virile race", he contended, could not be raised on white bread.

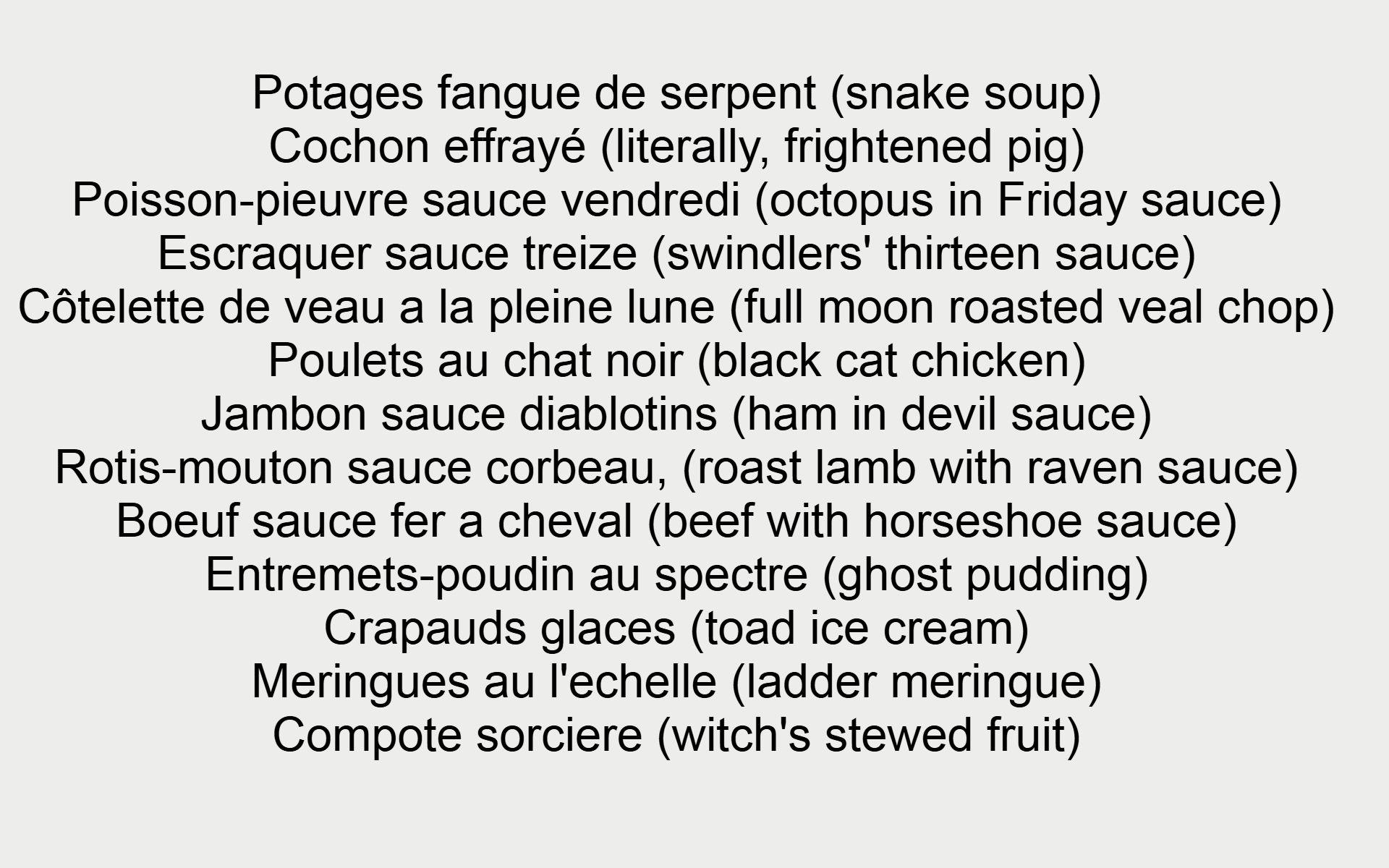

There were 13 dishes on the menu, all chosen for their disconcerting nature (although the sauces tend to do a lot of the heavy lifting)

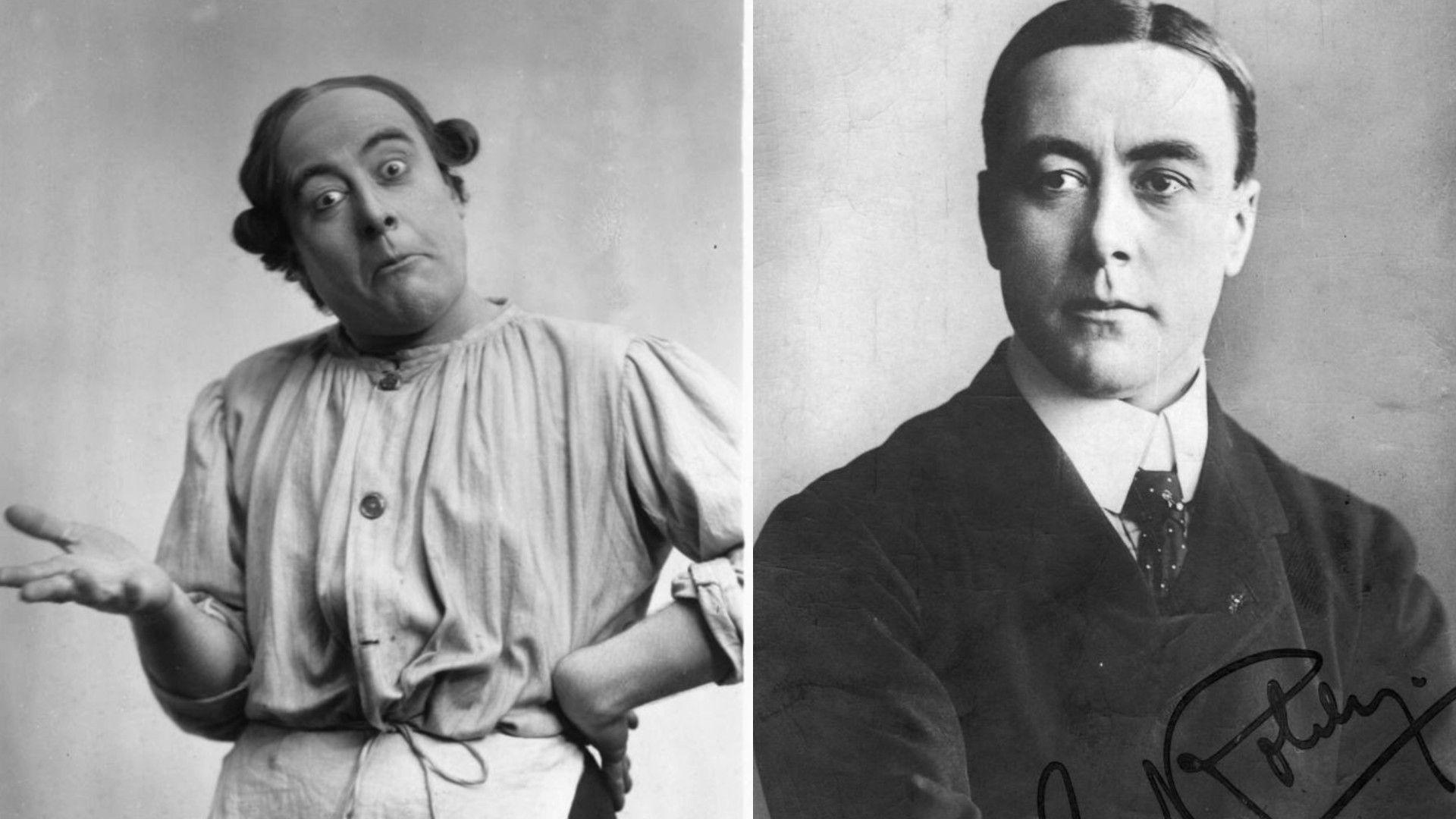

The 1928 cohort was also entertained by a young George Robey - an English music-hall comedian, apparently known for many years as "the prime minister of mirth".

The menu of that year's dinner, drawn by chairman Henry Furniss - a cartoonist formerly at Punch magazine - was particularly praised by the Sphere newspaper (although it is not known why the journalist felt a pen-and-ink witch needed to have her beauty assessed).

"Printed on bright red cardboard, it represented a most attractive young witch sweeping through the clouds on a besom, underneath being such objects as an owl, a spider, a horse shoe, an overturned salt cellar, a pair of knives crossed, a crowing cock, a wild cat, and a hideous imp running under a ladder."

George Robey - the "prime minister of mirth" - in the characters of pantomime's Goody Two Shoes (left) and sensible Victorian

Oscar Wilde was not alone in wanting to leave well alone - a sensitive soul wrote to the Daily Mail in 1926 to say: "Every heart knoweth its own sorrow and poking ridicule at other people's beliefs isn't cricket.

"Breaking looking-glasses, spilling salt, and monkeying with human remains at the festive board will not appeal to healthily minded folk."

A skull and crossbones is taken beneath a ladder at the Savoy hotel by club secretary Bill Randall

Regardless of concerns over healthy minds, the brazen flouting of superstition appeared to have little effect on the physical fitness or fortunes of the club's members.

Both the London and New York clubs boasted members were always healthy and prosperous.

Blanch claimed only one person from his London branch had died since the club was established (four years earlier) and that particular member had not paid his subscription.

Club chairman Albert Marchi, having recovered from two broken legs, is doused in salt at the Cafe Royal in London, 1939

But this continued good fortune was queried by a correspondent to The Times in 1894.

"Sir,

"I am greatly puzzled to comprehend in what way it combats - far less destroys - superstition.

"Surely the unluckiest and most superstitions of man - or even woman - kind could not reasonably expect any ill luck to follow in the train of a premeditated and prearranged salon, however artistically carried out.

"Ill luck, courteously and solemnly invited to dinner, with carefully selected and appropriate guests, would naturally leave its fateful weapons, with its hat and umbrella, in the hall.

"The virtue - if there be any virtue in superstition - consists in the act of occurrence, whether for good luck or ill, being purely accidental.

"Therefore an arranged performance of lucky - or unlucky - acts can have no significance whatever.

"Yours obediently,

"M J".

The Thirteen Club seemed to peter out at the beginning of World War Two, with the most recent contemporaneous report published in 1939.

Maybe poking fun at superstitions and coffin-shaped table decorations felt a little too close to the bone, luck notwithstanding.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external