The book that sank on the Titanic and burned in the Blitz

- Published

Only black-and-white images exist of the first "Great Omar" but a digital colourisation was created in 2001

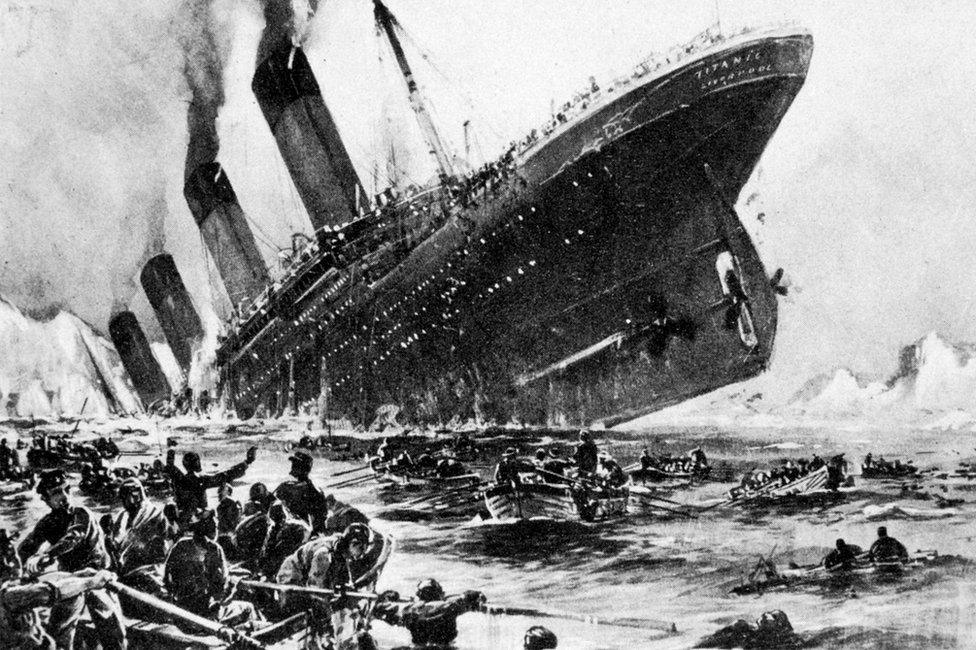

One of the most lavishly decorated books the world has seen was despatched from London to New York in April 1912. The jewel-encrusted edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám was taken aboard the RMS Titanic and sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, exactly 110 years ago.

A replacement was finished at great expense by the late 1930s but it was promptly incinerated by German bombers as the British capital was ravaged during the Blitz.

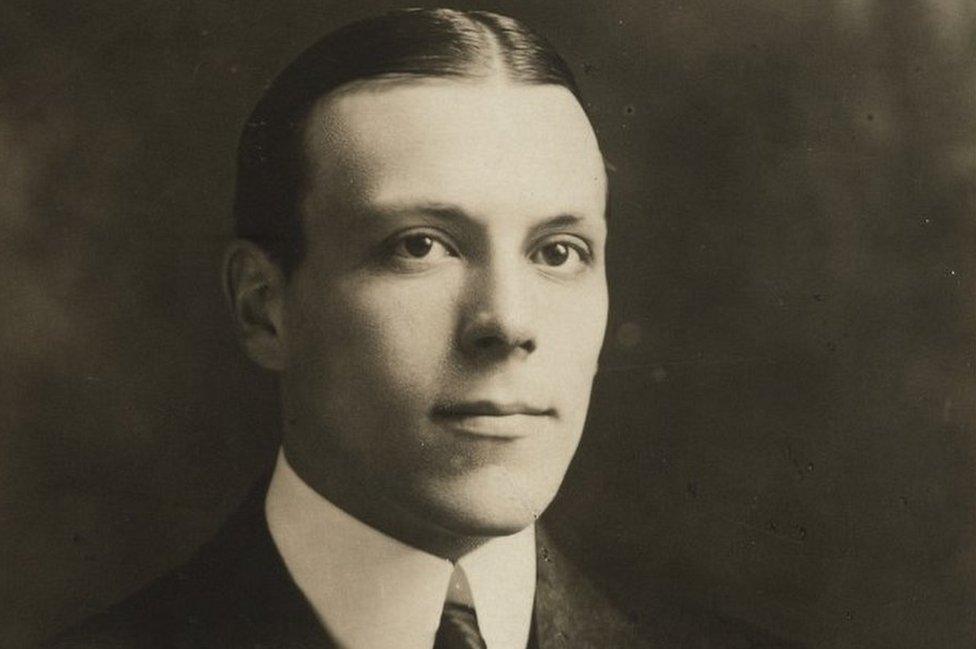

The young man behind this extravagant presentation of the polymath Khayyám's poetry would soon drown in an English seaside resort.

Would anyone dare to commission a third "Great Omar"?

'The greater the price the more I shall be pleased'

In 1911, Francis Sangorski finished work on a binding he had been labouring over at his Holborn workshop for two years.

It was breathtakingly magnificent.

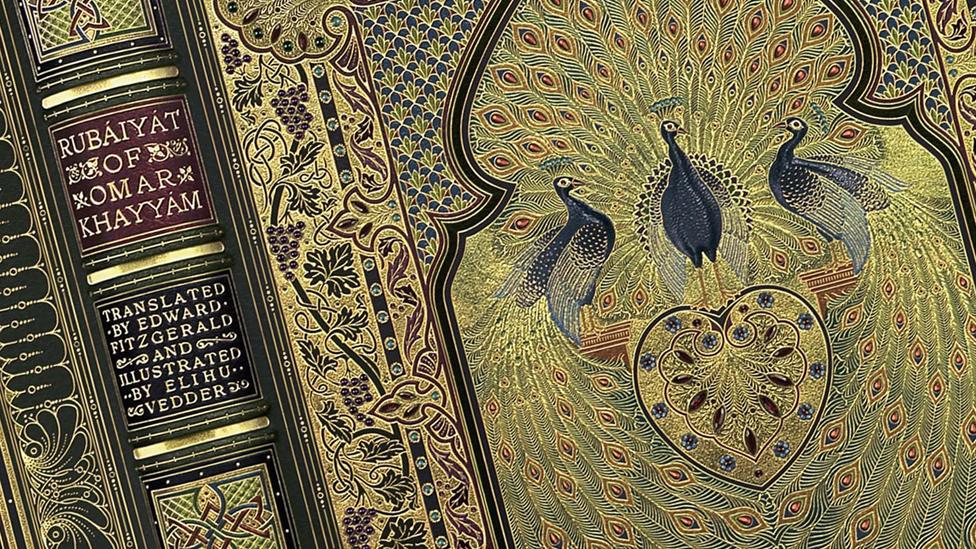

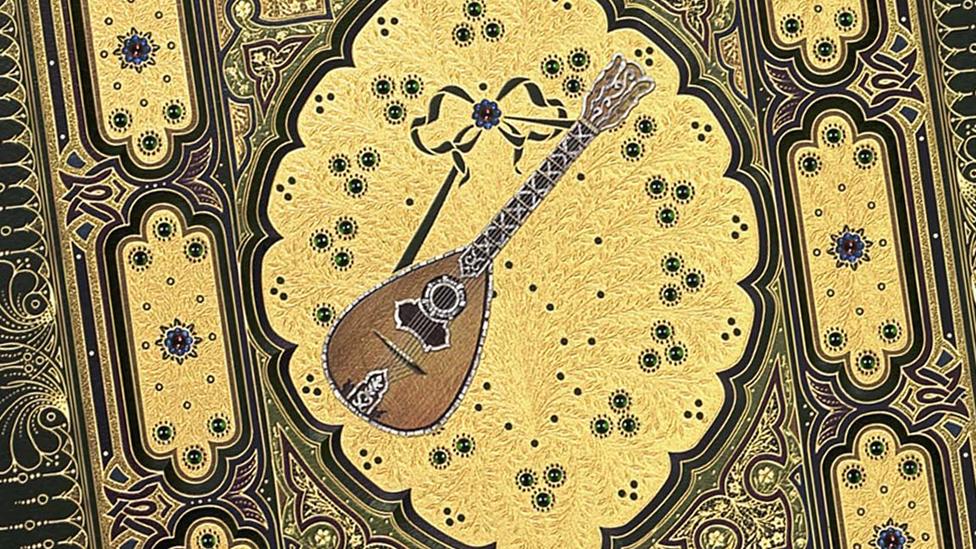

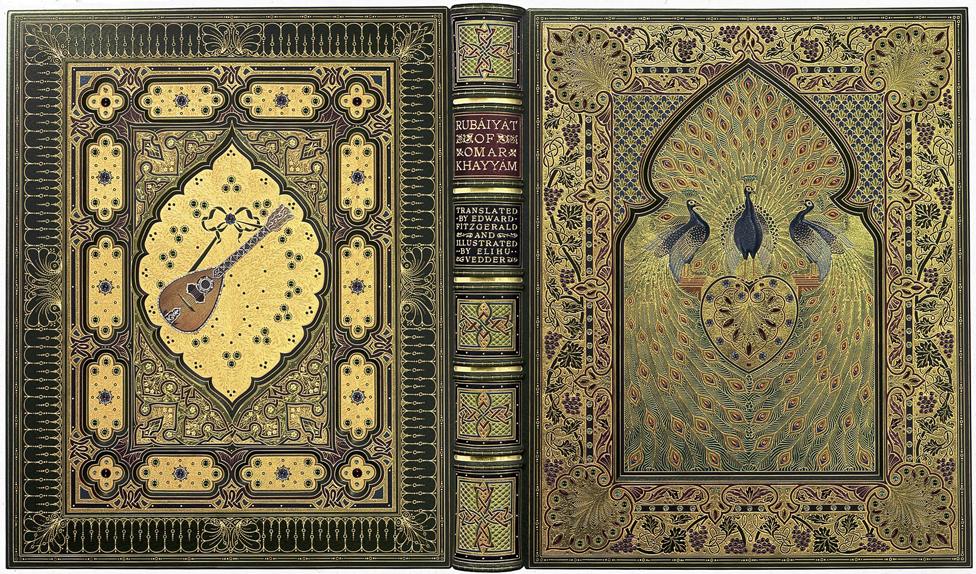

Measuring 16in by 13in (40cm by 35cm), the book was encrusted with 1,050 jewels including specially cut rubies, topazes and emeralds. About 100sq ft (9sq m) of gold leaf and some 5,000 pieces of leather were used in its creation.

Sangorski agonised over every detail, at one point borrowing a human skull so he could accurately depict it in his artistic vision. He even bribed a keeper at London Zoo to feed a live rat to a snake so he could capture the grisly image from first-hand experience.

The Daily Mirror considered the finished work to be "the most remarkable specimen of binding ever produced". Others simply described it as the "Book Wonderful".

It was given an enormous price tag.

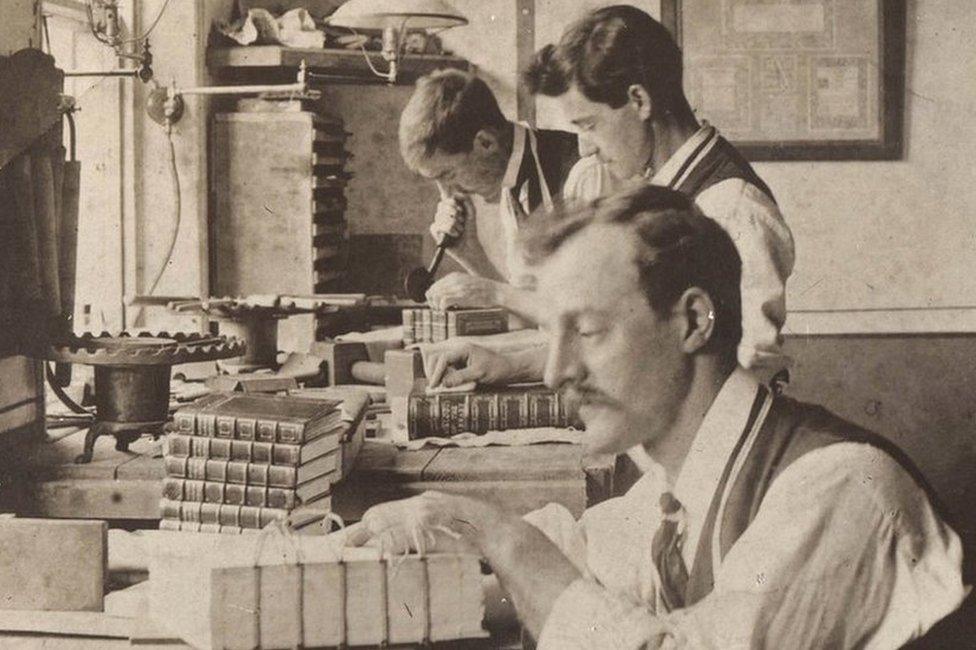

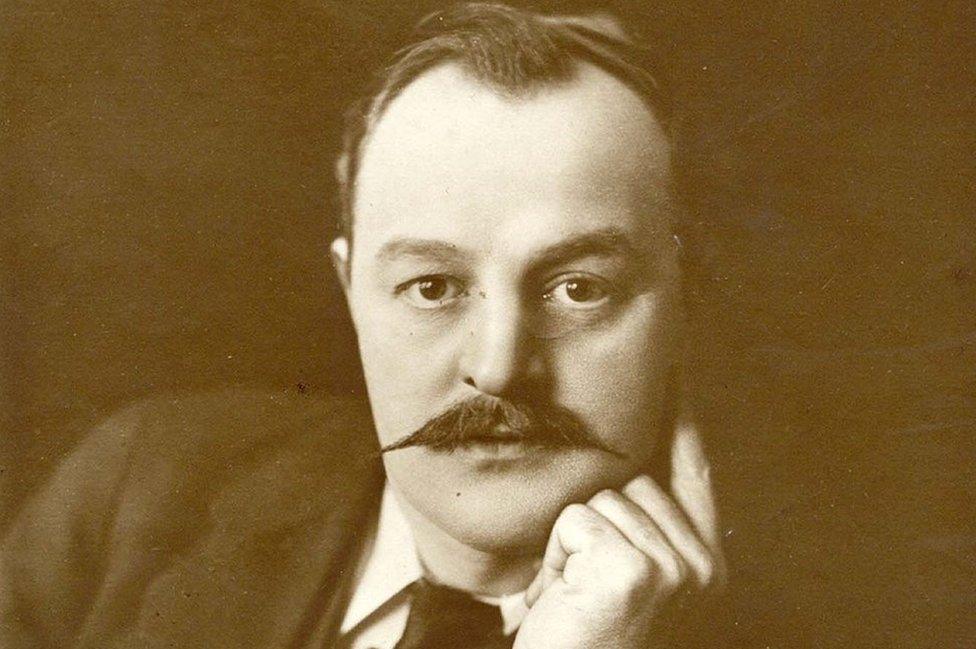

Bookbinder Sangorski and his business partner George Sutcliffe were already highly regarded for their elaborate jewelled covers.

"Real jewelled bindings were like Fabergé eggs," explains Rob Shepherd, managing director of Shepherds, Sangorski & Sutcliffe - the 21st Century iteration of the company the two men set up in the Edwardian era.

"They were of a level which would be very hard to replicate today as there's been a loss of skills over the years. The trade in those days was very skilled. They were extraordinarily talented craftsmen."

The pair had met in 1897 at evening classes, where they were taught by the best as apprentices to a line of craftsmen who went back to the Arts and Crafts movement's William Morris and included the eccentric TJ Cobden-Sanderson - a man who ended his career by throwing blocks of his own typeface off Hammersmith Bridge and into the River Thames so that nobody could copy him.

Sangorski and Sutcliffe's work stood out and they won prestigious bookbinding commissions, including for King Edward VII.

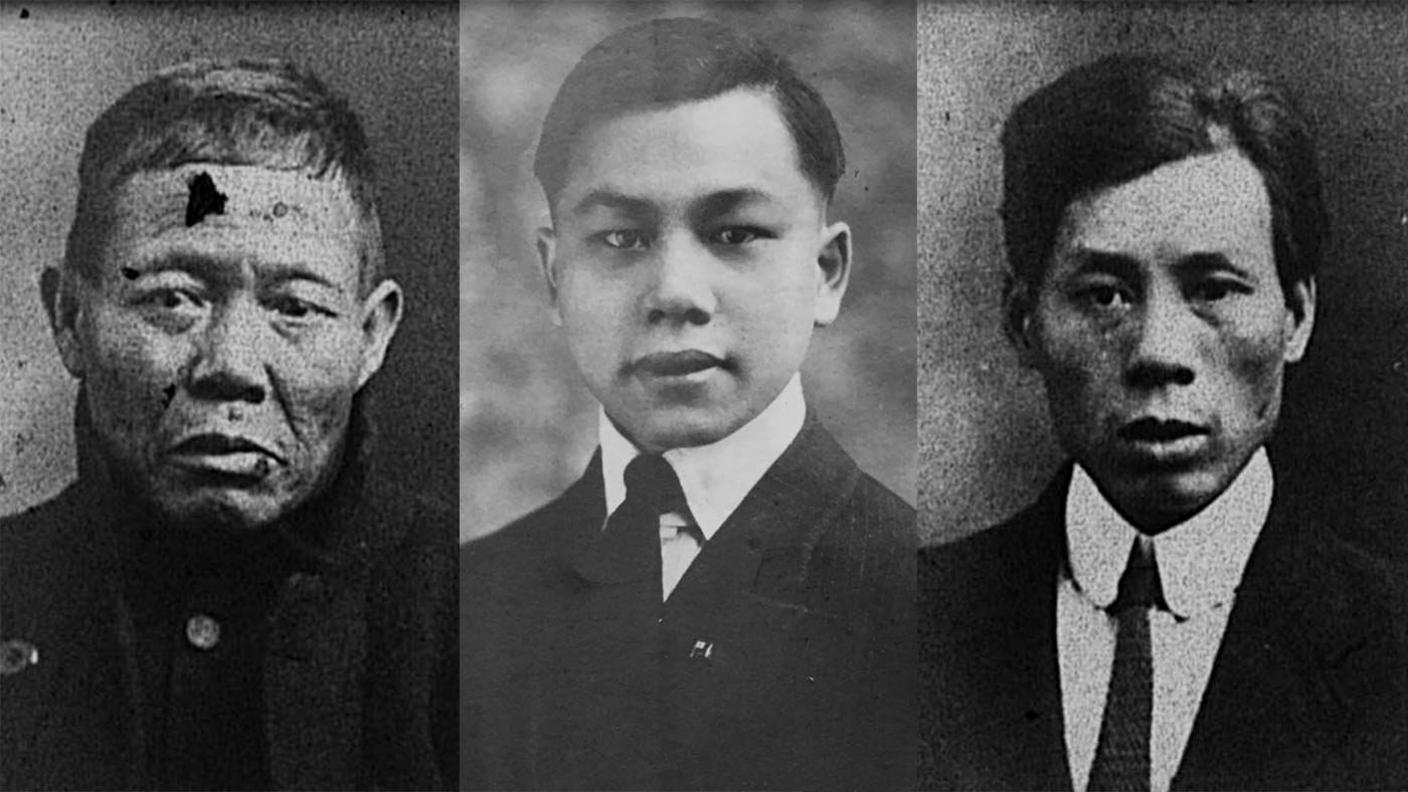

Francis Sangorski (front) and George Sutcliffe (middle) set up their bookbinding firm in October 1901

In 1907, Sangorski met John Stonehouse, manager of Sotheran's bookshop, which was founded in 1761 and is still in business today. Sangorski told him about his dreams for a book whose origins went back to the 12th Century.

While Sangorski had bound some versions of the renowned Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám before, the master craftsman said that this time he wanted to create a work featuring three peacocks he would surround with jewelled decoration "such as had never been seen before".

After much persuasion, Stonehouse agreed to commission it. He decided against telling his boss Henry Cecil, fearing Cecil would oppose the project.

Stonehouse stipulated a set of guidelines.

"Do it and do it well; there is no limit. Put what you like into the binding, charge what you like for it - the greater the price the more I shall be pleased - providing only that it is understood that what you do, and what you charge for it will be justified by the result, and the book when finished is to be the greatest modern binding in the world.

"These are the only instructions."

'The most remarkable binding ever designed'

Sangorski spent several months coming up with the book's design, including the snake and skull inside covers

The book consisted of six different panels: the front and back covers, the inside of the two boards - known as doublures - and two end leaves adorned with peacocks, plants, skulls and Persian patterns symbolising life and death.

For both boards, hundreds of pieces of coloured goatskin needed to be prepared and cut, numerous jewels had to be set in place each within their own individual clasp, and weeks were spent applying intricate gold tooling across all the surfaces.

"It was the most extraordinary piece of work," says Mr Shepherd. "It was very much of its time; the exuberance of Edwardian England just before war broke out."

Stonehouse was similarly impressed, describing it as "the finest and most remarkable specimen of binding ever designed, or produced, at any period, or in any country".

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

The philosopher, mathematician, astronomer and poet lived in what is now Iran, between 1048 and 1131. His achievements included creating the most precise solar calendar of the time but long after his death he would become more famous for his poetry, written in four-line verses known as quatrains

"These quatrains reflect the sceptic side of Iranian identity, which unbeknownst to many has been as active and profound as the spiritual one," explains Saeed Talajooy, an expert in Persian literature at the University of St Andrews

The poetry covered themes like nihilism, the brevity and the randomness of existence, as well as "the bitter understanding of having no control" and "drinking and forgetting the whole crazy business of life", Dr Talajooy says

A text attributed to Omar Khayyám was translated into English in the mid-19th Century by man of letters Edward FitzGerald. The Rubáiyát flopped at first but was happened upon by two Irish scholars, who helped to win the work widespread acclaim

Experts on the translated version, Sandra Mason and Bill Martin, consider it to be "one of the best-known individual poems on a worldwide basis"

'A fatality seemed to follow it'

With Henry Cecil by now aware of this incredible creation, and the extraordinary effort behind it, Sotheran's put the book on sale for £1,000 - the equivalent of £120,000 today.

"It was three times more expensive than anything else in Sotheran's stock. I think it was just too expensive for the UK market," says the bookshop's managing director, Chris Saunders.

And it wasn't only the price that was an issue. Some were far from dazzled by the Edwardian bling.

"I think that the Omar was probably seen, I mean undoubtedly by some people, as tacky. It was very nouveau riche and the old-fashioned aristocracy were probably quite embarrassed about it," says Benjamin Maggs, a bookseller from the historic London bookshop Maggs Bros Ltd.

A contemporary of that opinion was King Edward VII's librarian at Windsor Castle, Sir John Fortescue. He was among the first to be offered the chance to buy the Omar but declined, later describing it as "the most eminent failure, perhaps, that I ever saw", a work he found "absolutely inappropriate, ineffective and insignificant, and to me personally a positive distress".

A New York dealer called Gabriel Wells - formerly Weis - happened to be in London in the summer of 1911 and was more impressed. He offered £800 for the book.

This was declined by Sotheran's, which told him he could have it for £900. Wells refused and soon returned to the US.

With a lack of interest in Britain, it was decided the Omar should follow him to America, which had a more lucrative book market.

But when it arrived, there was a row about duty with US customs officials and Sotheran's refused to pay up, instead ordering the Great Omar back to London. As the months passed, a buyer still could not be found.

"A fatality seemed to follow the book," Stonehouse later wrote.

"Stonehouse simply had to sell the Great Omar to appease the owner, Cecil, whom he hadn't consulted about commissioning the book, and so in desperation offered it to Gabriel Wells for £900 and then £650," says Mr Saunders.

Wells wouldn't buy it.

"Cecil, in a fit of pique, demanded that it be sold as quickly as possible through auction."

And so on 29 March 1912, the book went under the hammer without a reserve price at the auction house Sotheby's. The London agent of Gabriel Wells paid £405 for it.

'The best place for it was under the ocean'

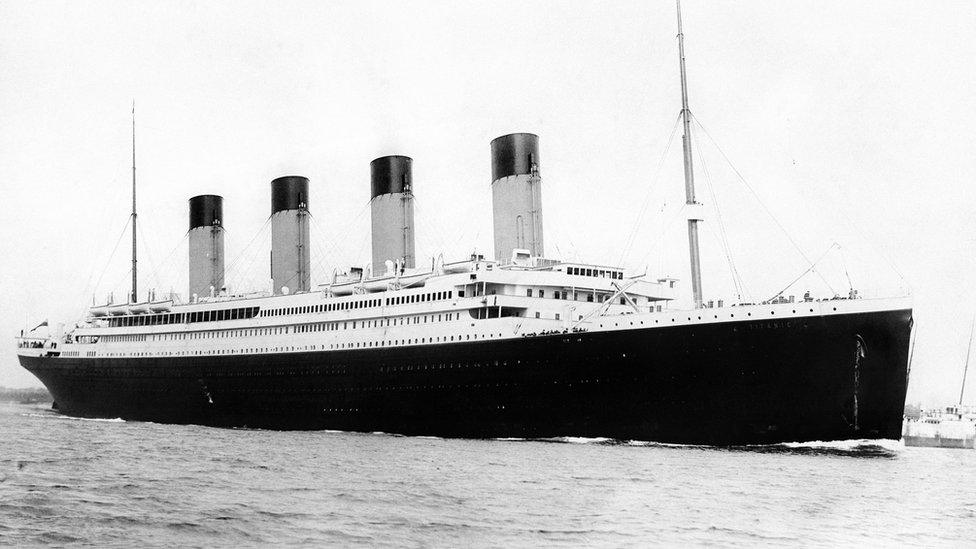

RMS Titanic set off on her maiden voyage from Southampton at noon on 10 April 1912

The Omar was readied for its to return to America. The book narrowly missed a crossing on 6 April and was instead taken aboard the next ship - RMS Titanic.

"The Sotheran's thing is so fascinating," Mr Maggs says. "The instructions that the guy who commissioned it gave: 'There is no limit' - just like for the Titanic itself there was no limit.

"'Make it as big as you possibly can', regardless of whether it's practical or sensible to do that."

The Titanic disaster, in which more than 1,500 people died, is of course one of the most famous events of the 20th Century, yet little is known about what happened to the Omar in its days aboard the ship.

Mr Shepherd considers it likely the book was in the safekeeping of bibliophile Harry Elkins Widener. The 27-year-old and his parents, who came from the two wealthiest families in Pennsylvania, were among the most prominent passengers on the Titanic.

"The duty on the book would have been enormous, so he could have been asked to carry it on under his arm," according to Mr Maggs, who said Widener knew Wells. The shrewd book dealer had already spoken in the press about his disgust that he might have to pay tax on the import.

After his death, Harry Elkins Widener's book collection was donated to Harvard University where a library was built in his honour

An avid collector, Widener was returning to the US following a book-buying trip to London.

According to Don Lynch, official historian of the Titanic Historical Society, on the night of the disaster the Wideners held a dinner in the ship's a la carte restaurant in honour of the RMS Titanic's captain Edward Smith. As they ate, warnings were being sent about the sighting of icebergs that might imperil the crossing.

Sitting alongside Smith and the Wideners were Mr and Mrs John B Thayer of the Pennsylvania Railroad; another wealthy Philadelphia couple Mr and Mrs William E Carter; and Major Archibald W Butt, US President William H Taft's military aide.

By the time the ship struck the iceberg, the party had broken up. Harry Widener was said to have been in the smoking lounge at the moment of impact.

Like his father, the bibliophile would not survive the disaster.

Widener's mother and her maid were among the 713 people rescued from the water - precisely 110 years ago, on 15 April 1912

The Great Omar was far from the only expensive item lost in the sinking. Other pieces included the Merry-Joseph Blondel painting La Circassienne au Bain, which was valued at over $100,000 (nearly $3m today), and an engine from the first flight machine, which was being shipped to the Aero Club of America.

Mr Lynch says the Omar was "perhaps the most well known" of the lost treasures, as is evidenced by its mention in the preface of Walter Lord's book, A Night To Remember, the work that inspired James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster film.

As for the likely state of the book 110 years after the sinking, Mr Lynch, who has joined dives down to the wreck, believes "it depends entirely upon how well it was packed and where in the ship it was stored".

"Once exposed inside the ship, if indeed it was exposed, the leather may have been eaten away but of course the precious stones would remain."

And there the Omar presumably still lies, some two and a half miles beneath the waves - not that everyone was displeased about its fate.

Sir John, the king's librarian, would declare that the bottom of the Atlantic was decidedly "the best place for it".

'Life for him had only just begun'

Francis Sangorski was survived by his wife and four children

The fate of the book was one of the many thousands of Titanic stories reported in newspapers across the world.

"Everyone lost out on their investments in the Great Omar," Mr Saunders says.

Although the destruction of the Sotheran's accounts in the Blitz of War World Two means it's unclear how badly the business was affected, he says there were tensions as a result of the Omar's loss.

"Sotheran's relationship with Sangorski & Sutcliffe was soured over disputes over costs and payments," Mr Saunders says.

Further tragedy was to follow only 10 weeks after the sinking of the Titanic.

Francis Sangorski was on holiday with his wife and their four children on the English south coast on 1 July 1912, when he decided to go for a dip in the sea at Selsey Bill in Sussex.

Sangorski's grave, designed by his business partner, featured various intricate patterns

An inquest heard that he had been knocked off his feet by a strong current. A man in the sea with Sangorski tried to save the famous bookbinder, who couldn't swim, but left him to assist his female companion when he heard her cries.

The body of 37-year-old Sangorski was discovered an hour and a half later.

He was buried in St Marylebone Cemetery, now East Finchley Cemetery, his ornate gravestone designed by his partner Sutcliffe.

John Stonehouse mourned the loss of both the man and his art.

He wrote: "Life for him as a great master craftsman had only just begun."

'The more you protect it, the worse you make it'

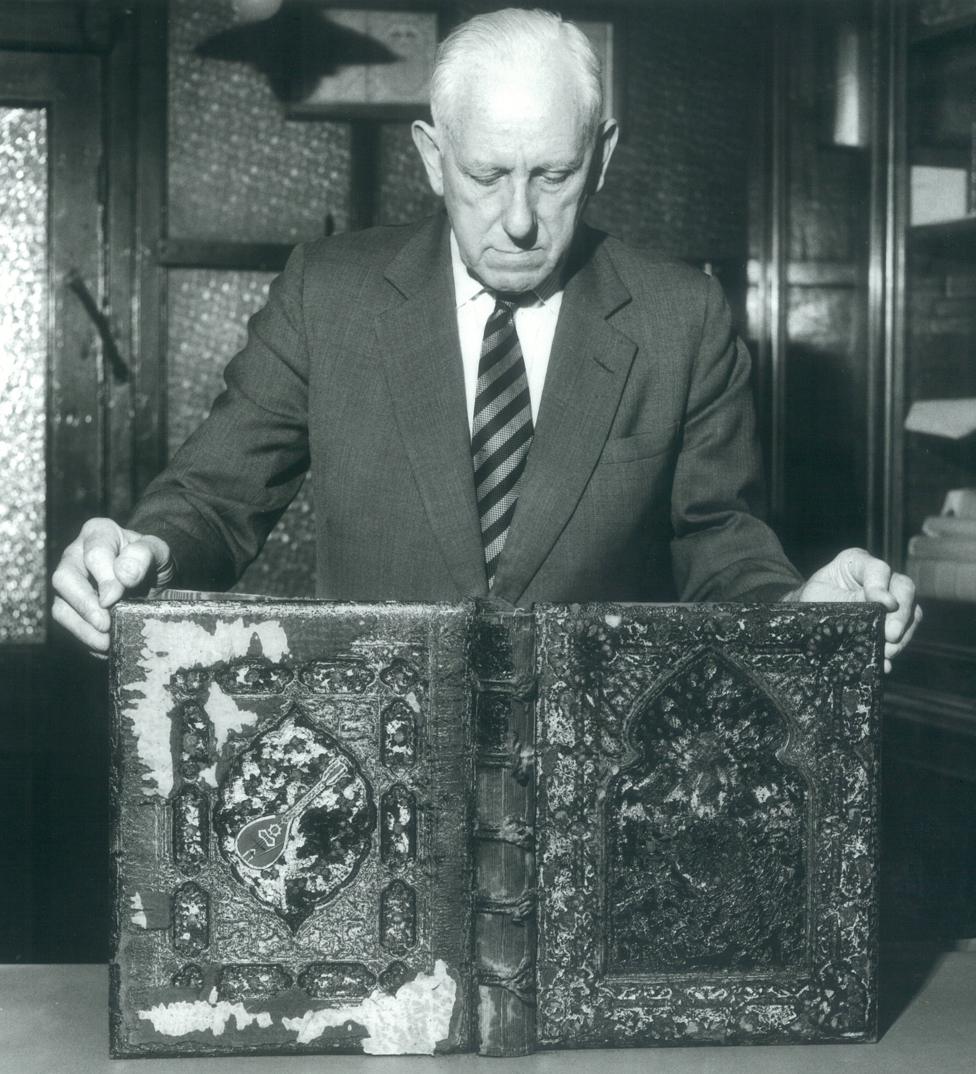

Stanley Bray holding the remains of the second Omar, which was badly damaged in the Blitz

Sangorski & Sutcliffe continued as a company in spite of the loss of its co-founder.

In 1924, George Sutcliffe's nephew Stanley Bray joined as an apprentice.

Eight years later, he came across Sangorski's original drawings and tooling patterns for the Omar in the company safe and decided to recreate the great work.

"I think he was basically trying to impress his uncle," says Mr Shepherd, who wrote about the company in his book The Cinderella of the Arts.

Working in the office and at home, Bray spent the 1930s toiling over the second jewel-encrusted Great Omar. The binding was finished just as war engulfed Europe.

It was decided that the book needed protection from bombing raids and so it was wrapped in protective material and placed in a secure vault in Fore Street in the City of London.

Fore Street was the first road in the City that the German bombers hit. Subsequent air raids in 1940 and 1941 levelled nearly all the buildings in the area.

The rubble was eventually cleared and the safe containing Bray's Omar was located, still intact and apparently unscathed.

But when it was opened a ruined black mass was discovered, the sheer heat of the fire having melted the leather and charred the pages.

The ward of Cripplegate, which contained Fore Street (pictured), was so badly hit by air raids that by 1951 only 51 people were registered as living in the area

"It was essentially partly the protection that damaged it, so it was almost as a result of their efforts to keep it safe - it wasn't safe - which I also find interesting, because the more you try to protect this book the worse you make it," Mr Maggs says.

"So like with the Titanic, you think, 'What's the safest way to possibly send this book to America - surely the unsinkable ship is the safest way to send it?' And so this book kind of consciously conspires against you and the more you try, the worse the result."

Of course, the company's premises on Poland Street in London's Soho went through the war undamaged, in spite of a firebomb once landing metres away.

With Britain under siege from enemy attacks, Bray was accepting of the destruction of the Great Omar, though, remarking: "If this is all I am going to lose, I shall be lucky."

'It's become a kind of symbol'

Stanley Bray took some 4,000 hours to finish the third Omar

Two lost books and years of lost work did not diminish Bray's enthusiasm for the Omar and as the country celebrated the end of war on VE Day in 1945, he began work on the third.

Many of the jewels that had survived from his previous version were recycled.

The running of Sangorski & Sutcliffe limited the amount of time he had to work on it, so the binding became more of project for his retirement in the 1980s. But after an estimated 4,000 hours of toil, the third Omar was finally finished.

For Mr Maggs, there's something that's almost "romantic" about the work Bray put into that final version.

"The fact that Stanley Bray made it again, twice - at that point he's not doing it to make money, it's something else: it's become this kind of symbol.

"It's like the most decadent, luxurious, capitalistic book has surpassed itself and has become genuinely priceless and has become a thing that is made for the sake of making it."

Bray presented the third Omar to the British Library. His obituary in December 1995 described the book as "a monument to a long life's work", external.

The third Omar is held in the British Library. Access to it is rarely permitted

The Omar and the related material were permanently left to the institution after the death of Bray's widow Irene in 2004. The book remains among the library's collection, although access to it is rarely permitted.

For now at least, it appears any "curse" has not taken hold.

Bray himself never thought much of the idea, anyway, commenting about the design: "I am not in the least bit superstitious, even though they do say that the peacock is a symbol of disaster."

"Some people say peacocks' feathers are omens of death but Stanley Bray lived to an old age," says Mr Shepherd.

"Indeed, the book probably kept him going."

'It won't come with you'

Sangorski's name is now barely readable on his gravestone

In East Finchley Cemetery, the gravestone of master bookbinder Francis Sangorski is hard to find.

Tucked beneath a tree among other stones, its exquisite carvings are weathered and worn - like his magnum opus at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

For Mr Maggs, the story of the Great Omar chimes neatly with the theories of Omar Khayyám, whose wisdom inspired the master craftsman to commemorate the poet-philosopher in gold, jewels and leather.

"In a way it's perfect; the whole tale is a meta-story because part of the text is about, 'Sure, when you've got it, use it, enjoy your life, but know it will end, be aware of it' - it's almost like a sort of curse.

"That's what the Great Omar is telling you," Mr Maggs says.

"If you can afford it, why not? Do it. But be aware that you'll die and it won't come with you."

All images subject to copyright

Story edited by Ben Jeffrey

- Published16 April 2021

- Published30 April 2021

- Published21 January 2020

- Published24 June 2021

- Published29 September 2019

- Published3 September 2019

- Published16 October 2019

- Published5 April 2012