There are many moments where you could begin the story of Grenfell Tower. One is in 1972, when a section of cramped west London terraced streets in Notting Dale had just been torn down.

The vision was to replace them with an entirely new community. The Lancaster West Estate would have three blocks, each leading to a central 24-storey concrete tower - Grenfell.

Early plans included shops, offices, a swimming pool and gardens. But plans for these amenities were quickly abandoned.

Just five years after Grenfell Tower opened in 1974, the early optimism had faded. Residents were already complaining about vandalism, broken lifts and lights, and of the estate feeling impersonal.

More than 30 years later, some residents spoke of slum-like conditions. Then a new refurbishment began. It promised lower heating bills, new boilers, a completely new look for the building.

It was this refurbishment that would cover the tower’s external walls with combustible materials and lead to the catastrophic fire that killed 72 people in 2017.

Next week, the public inquiry into the disaster will produce its final report, setting out what led to the worst residential fire since World War Two - one the inquiry has heard was both foreseeable and preventable.

I’ve been covering that inquiry since 2018, listening to hundreds, possibly thousands of hours of evidence about the layers of opportunities missed and warnings unheeded at every level.

This is a story of corporate deceit, government deregulation drives and a construction industry in a race to the bottom.

Guidance, not rules

Dr Barbara Lane is a fire safety specialist who was one of the inquiry’s main expert witnesses, giving days of evidence. She’s upfront and straight-talking, often telling the barristers why their questions were wrong.

In person, though, when she talks about her experiences inside the block in the fire’s aftermath, her manner is completely different.

Quietly, she recalls the darkness, the black smoke-stained walls, a half-burnt bedroom where only a cot remained. What struck her was the humanity of it, she says: “What the humans went through.”

To understand how a refurbishment could have created the possibility of such a disaster, we have to look at what underpinned all that work - the building regulations.

When Grenfell was constructed, those regulations were set by an act of parliament.

For the past six years, a public inquiry has heard evidence about the worst residential fire in UK peacetime. Kate Lamble has reported on it from the beginning. She examines what created the conditions for a disaster that was both foreseeable and preventable.

In the 1980s, however, Margaret Thatcher wanted to reduce government intervention. Regulations stopped listing precise rules, simply describing instead what the end result should be.

The external walls of a building, the regulations now stated, should simply offer “adequate resistance” to fire - a standard the public inquiry has already concluded Grenfell Tower did not meet.

How to achieve this was contained in government guidance, not regulations.

Dr Lane says this shift gave the industry a false confidence to not really care as much as they should about safety.

Costly warnings

As early as the 1990s, there were signs of weakness in the new guidance. It suggested that cladding panels should meet a certain fire safety standard known as Class 0.

But materials which met that standard were soon involved in fires.

On 11 June 1999, a dropped cigarette started a fire in Garnock Court, a 14-storey block in Irvine, Ayrshire. News reports described it igniting like matchwood. One man was killed.

The corner flats had been surrounded by plastic cladding that should have met the Class 0 standard.

The Garnock Court fire led to the tightening of the rules in Scotland - but combustible cladding was still permitted in England and Wales

Brian Donohoe, the then-local MP, says he pushed for all combustible cladding to be banned and removed. His Labour colleagues, then in government, did not agree. One secretary of state, he says, told him “it would cost millions”.

A parliamentary select committee recommended that all cladding on high-rise buildings should either be entirely non-combustible, or put through large-scale fire tests to prove it wasn’t a risk.

These tests were introduced, but Class 0 remained in the guidance. England and Wales continued to be a market for combustible cladding.

Watch on BBC iPlayer

I Was There: Grenfell

- Attribution

Lack of urgency

Garnock Court wasn’t the only warning.

In 2009, flames at Lakanal House, a south London tower block, spread rapidly into combustible panels outside. Six people were killed.

Four years later, a coroner called for a review of the building regulation guidance.

The government agreed to do this by 2016 or 2017. But by the time of the Grenfell fire, this work had not begun, despite repeated demands from MPs in the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Fire Safety.

This was a period of snap elections and referendums. The minister responsible for building regulations changed three times in as many years. Ministers also say they were not briefed on the importance of the Lakanal House fire.

Statistics also showed fewer people were dying in fires. One minister told the inquiry they took comfort from that that there was no urgent problem.

‘Health and safety gone mad’

At the public inquiry, one junior civil servant admitted there were a number of occasions “where I could have potentially prevented this happening”.

Brian Martin advised ministers on the part of the building regulation guidance that covered fire safety. Over the years, he was given a series of warnings about the use of combustible materials on high-rise residential buildings.

After a cladding fire in Dubai in 2015, Mr Martin was approached by industry figures who told him that the combustible products involved in the blaze - the very type of cladding later installed on Grenfell Tower - were being sold in the UK.

Mr Martin has acknowledged he did not escalate that warning to his bosses. “I struggle to come to terms with why I didn't do that,“ he told the inquiry.

We should remember the 2010s were the era of slashing red tape, of health and safety culture "gone mad". According to Mr Martin: "Regulation was a dirty word."

Under the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, in 2011 a policy of “one in, one out” was adopted. Ministers could not introduce a regulation unless they abolished one too. By 2016, under the Conservatives, that became “one in, three out”.

Brian Martin and his superiors have said they understood fire safety was not exempt from the government’s deregulation drive - something ministers have strongly denied.

The Department for Levelling Up Housing and Communities says it has since taken a number of actions, including banning combustible materials on high-rise buildings.

‘Misleading half-truth’

It was the view that first attracted Marcio Gomes to his 21st-floor flat in Grenfell, he tells me. On New Year’s Eve, he would invite friends to watch the fireworks.

He remembers when talk started of refurbishing the building. Posters showed how it might look with metallic-looking cladding fitted. Residents were asked which colour they’d prefer, which finish? Fire safety was never discussed.

At the public inquiry, there have been questions about how each of the materials installed on Grenfell were tested.

The cladding was made of thin sheets of aluminium with a core of combustible plastic. The inquiry has already found it to be the main cause of the spread of the fire.

It was made in France by a company called Arconic and came with a certificate that said a “standard panel” met the fire safety standards contained in the government guidance.

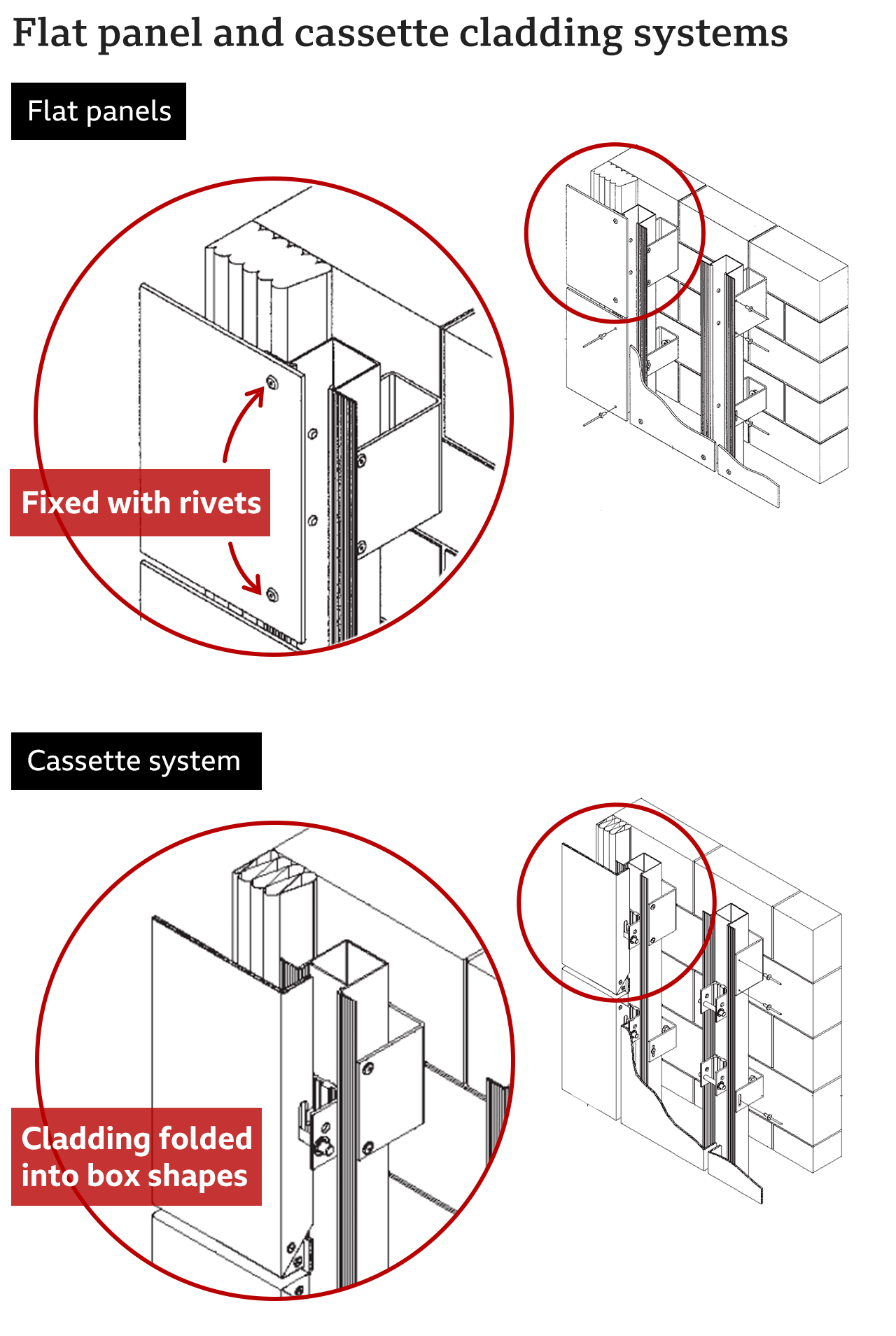

However, Arconic suggested their materials could be cut in two different ways.

The first option, flat panels, had achieved the European fire standards described. The other option, cassettes, where the material had been bent and folded, had not. In fire tests, these performed “spectacularly” worse.

It was the bent cassettes that were fitted on to Grenfell Tower.

Arconic received their certificate by only providing the results of the successful test on the flat panels, not the failed test on the cassettes.

At the public inquiry, Claude Schmidt, the managing director of the company’s French office, accepted this could be seen as a “misleading half-truth”, but denied information was deliberately withheld.

Arconic told us it acknowledges the part it played in supplying a material involved in the fire. But it says responsibility for fire safety compliance does not rest with it as the supplier, but with those who selected it for use.

‘Why are we using them?’

Ed Daffarn moved into Grenfell in 2001. In the following decade he describes the building falling into a period of managed decline.

He welcomed the idea of a multi-million pound refurbishment.

The initial design work was given to Studio E, architects who had worked on a nearby school and leisure centre.

Only they had never clad a high-rise building before. A competitive process legally required for large expensive projects was avoided because Studio E deliberately deferred part of their fee - bringing down the upfront costs.

At a meeting with the Tenant Management Organisation that ran the building on behalf of the local council, Ed Daffarn asked if the architects had experience with tower blocks and if not: “Why are we using them?”

He says he never received an answer.

Ed Daffarn lived on the 16th floor of Grenfell Tower

During the refurbishment, Mr Daffarn says he can’t remember “a single meeting where I felt that our views or what we wanted was being listened to”. Many residents joined action groups to raise concerns about a range of fire safety issues including out-of-date equipment.

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea has acknowledged residents were not listened to as much as they should have been.

The lead architect on the Grenfell refurbishment, Bruce Sounes, told the inquiry he did not familiarise himself with building regulations on fire safety. Nor did Studio E check the suitability of the materials they specified.

At Studio E’s request, a company called Exova wrote three fire safety strategies for Grenfell Tower. All three stated the refurbishment would have no adverse effect on external fire spread. None even acknowledged the building would be clad.

Exova staff have said they thought the architects would ask them to look at the cladding if necessary.

‘Buck-passing’

With the initial design completed, the refurbishment was handed to a construction firm, Rydon, which became legally responsible for the design and build.

Rydon’s bid had been lower than their nearest competitor - but still £800,000 over budget.

In cases like this, what commonly happens next is a process known as “value engineering” - finding ways to cut costs without affecting performance.

Two days after Rydon was officially appointed as the contractor, it sent details of proposed savings to the Tenant Management Organisation which ran the building.

Non-combustible metal cladding, which the architects had preferred, would be replaced with a cheaper alternative, saving nearly £400,000.

Grenfell Tower in 2011 - before the cladding was installed

Based only on looks, the council’s planning department chose cassette panels, the most dangerous form.

This cladding, with its combustible plastic core, was the primary cause of the fire’s spread.

As is common in construction, Rydon hired sub-contractors, who then often hired their own. Almost all have argued they did not hold ultimate responsibility for checking the work for fire safety, pointing instead to another firm they presumed was doing it.

The lead counsel at the public inquiry called this a “merry-go-round of buck-passing”.

In 2016, the local council’s building control department signed off the refurbishment. The council accepts it should not have done so.

The tower was transformed, but residents immediately spotted problems.

“There were massive gaps above, below and beside the windows,” Ed Daffarn says.

In the early hours of the 14 June 2017, those gaps would fill with smoke.

Prepared and trained

The first fire engine arrived at Grenfell within five minutes. Crews saw wispy smoke and an orange glow. To them, this seemed normal. There were around five fires a week in high-rise flats in London.

But this fire would quickly become something else, as it spread out of the window and climbed up the outside of the building through the combustible cladding and insulation.

Having watched dozens of firefighters give evidence to the inquiry, it’s hard to think of even one who recognised what they were watching was a cladding fire.

Front-line firefighting staff hadn’t been trained about the risks of fire spreading across the outside of a high-rise building. That is even though Andy Roe, who now leads the London Fire Brigade (LFB), accepts his organisation knew of these risks.

”It's fair to say that we didn't train people adequately enough,“ he says. He accepts this was a failure of the organisation’s obligation to its staff.

Still, Mr Roe thinks it would have been very hard to foresee the extremity of the Grenfell fire.

For more than an hour and a half, the LFB operated on the principle of “stay put” - advising residents they would be safest to remain in their flats until help arrived.

This policy relies on flames and smoke being contained in a flat for at least 60 minutes, giving firefighters time to reach them. But at Grenfell, flames climbed 19 floors in just 18 minutes.

Mr Roe recognises residents were advised to stay put for too long and that advice would have had an impact on residents’ decision-making that night.

“Stay put” is still used by the LFB but it has now trained its crews to evacuate when necessary.

Unnecessary expense

Ed Daffarn was woken by a neighbour’s smoke alarm around 01:10 on 14 June 2017. When he opened his door, he was met with a wall of smoke.

The spread of this smoke was aided by something that seems small, even insignificant: automatic door-closing mechanisms.

These are meant to keep smoke inside a flat if a resident has to run outside to safety. But at Grenfell, not every door closed behind people as they fled.

Workmen had removed some door-closers during repair work - including one flat on Ed Daffarn’s floor. He’d complained about it himself.

Both the Tenant Management Organisation and Grenfell’s owners, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, were aware of this issue.

More from InDepth

Israeli settlers are seizing Palestinian land under cover of war - they hope permanently

- Published27 August 2024

Riots show how the UK's far right has changed

- Published21 August 2024

Power, oil and a $450m painting - insiders on the rise of Saudi's Crown Prince

- Published19 August 2024

The inquiry has been told a plan was put together to regularly check door-closers. But the idea was rejected.

The council told us that it could and should have done more to keep its residents safe before the fire. It told the BBC it was wrong to tell the Tenant Management Organisation there should not be an inspection programme.

On the night of the fire, flames quickly reached Ed’s neighbour’s flat, the one without an automatic door-closer. The resident ran out, leaving the door open, and smoke poured out into the hallway where Ed would find himself.

Ed became lost in the corridor. As he panicked, a firefighter grabbed him and pulled him into the stairwell.

Opportunity for change

These, then, are the layers of missed opportunities, the dozens of chances over decades for someone to step in, to ask a question, to change history.

At the end of the hearings, the lead counsel to the inquiry said it will “be able to conclude with confidence that each and every one of the deaths that occurred in Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 was avoidable”.

For me, Grenfell also reveals a series of unspoken truths about the British system.

How safety was regarded as, at best, not as a vote-winner; and at worst as an obstruction to the economy. How regulation was viewed as guidance to be bent. An inherent lack of curiosity - a presumption that someone else would check, that something that bad couldn’t happen here.

More than 3,000 high- and mid-rise buildings across England are still being monitored because they have unsafe cladding.

The recommendations made next week will attempt to ensure such a disaster can never happen again.

As always the government will have no obligation to carry these out. Nor is there a formal process to monitor what they reject or why.

It is another opportunity for change. One we may yet reflect on after future fires.

Top picture: Getty Images

Source for flat panel and cassette graphic: British board of Agrément

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Get in touch

InDepth is the home for the best analysis from across BBC News. Tell us what you think.