Grenfell Tower inquiry: 9 things we now know about the cladding

- Published

Panels made from plastic and aluminium were installed on the sides of Grenfell Tower to make it warmer and drier. But the cladding has been blamed for helping flames to spread when fire broke out in June 2017, resulting in 72 deaths.

Hundreds of thousands of people are living in buildings with similar cladding, which must now be removed at enormous cost, resulting in a crisis in building safety.

The public inquiry has questioned key employees of Arconic, the multinational metals company that made and supplied the cladding sheets for Grenfell.

So, what have we discovered?

1. This type of cladding burns easily

The big concern is about a type of cladding called Aluminium Composite Material, or ACM. It is made from polyethylene (PE), plastic sandwiched between two very thin sheets of aluminium.

France-based Arconic Architectural Products called its version of the product Reynobond PE, and sold it to big building projects all over the world. What is not in doubt is that this product is highly flammable.

2. The cladding consistently failed fire tests for 12 years before Grenfell

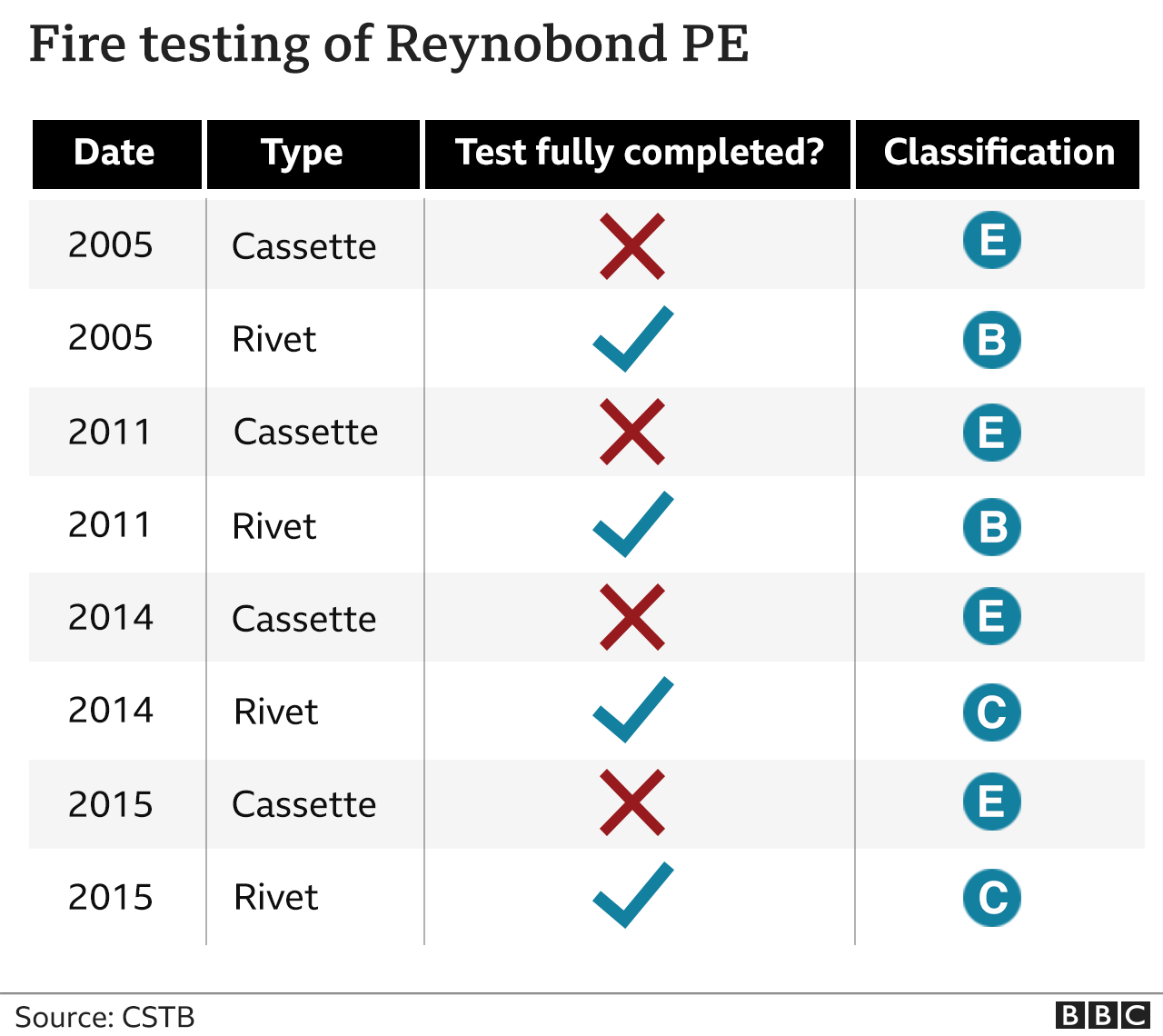

In 2005, Arconic commissioned tests in France to see how its Reynobond product would perform in a fire when installed in two standard ways known as "rivet" cladding systems and "cassette" systems.

Rivet systems are simply installed straight onto mounting brackets, with rivets. In "cassette" systems the cladding is folded into box shapes, like old-style cassette tapes, to hide the fixings.

Crucially, the cassette system was the design used at Grenfell Tower.

When the cassette version of Reynobond PE was tested, it failed to complete the test.

In the standard European fire test the results are classified from A1 (best) to F (worst).

The cassette version was given a rating of E. The folding appeared to allow flaming pools of plastic to form.

This version was to be tested again in 2011, 2014 and 2015. Each time the rating was E. Even the better-performing rivet version only managed a class C in more recent tests.

3. It didn't meet building standards in England

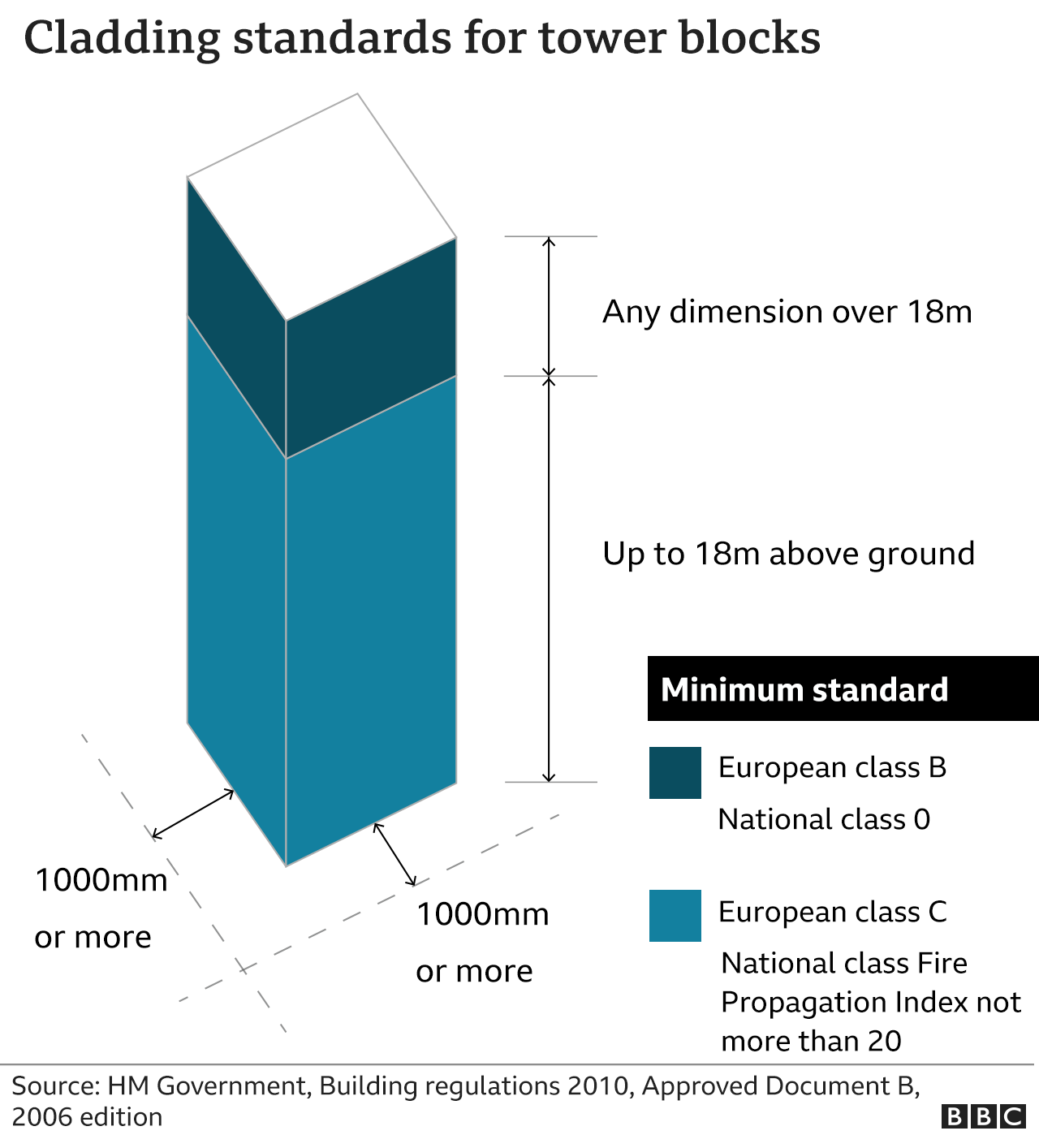

The bible for the construction industry in England is called Approved Document B. It sets out the fire performance standards required for all buildings.

Only products with a rating of B in the European fire test can be used on tall buildings above 18m. The Reynobond cladding with class E fell short of the required standard.

England has its own system of fire test ratings. The best rating is Class 0 (zero), which is acceptable instead of the European standard. But Reynobond PE's French manufacturer had never put this cladding through the relevant tests, the inquiry was told.

There were other ways to meet the regulations, including testing a design in a full-scale mock-up. That didn't happen at Grenfell Tower. Arconic now says it should have.

4. Arconic 'misled' British standards board

Test results are commercially sensitive. So a specialist body, the British Board of Agrement (BBA), assesses them and issues product certificates.

The BBA decided the evidence from the more successful European tests carried out on the Arconic cladding meant it "may be regarded" as having met the British standard.

But the Board was never shown the class E ratings for the cassette version of the cladding and knew nothing about them until a BBC investigation in 2018.

Arconic's president in France, Claude Schmidt, was forced to admit at the inquiry this would have "misled" anyone reading the certificate, including British architects.

5. The Grenfell disaster was predicted, a decade before

In 2007, Arconic marketing manager Gerard Sonntag attended a talk given by a consultant Fred-Roderich Pohl, who gave a dramatic warning of the risks of Aluminium Composite Material cladding. He said it had the same "fuel power" as a 19,000 litre truck of oil.

But he went further. Pohl reportedly asked "what will happen if only one building made out of PE is on fire and kills 60 to 70 persons."

Exactly the circumstances of the Grenfell fire in 2017.

Mr Sonntag's account of the presentation has been uncovered by the inquiry, which included it in evidence of what the company knew and when.

Seventy-two people died as a result of the fire

6. The company was aware of a 'Towering Inferno' warning following fires in the Middle East

In May 2013, the BBC reported on a worrying series of fires in the Middle East, blamed on ACM cladding from several producers.

Arconic noticed. Employees circulated an email they had received from a sales manager working for a competitor, Richard Geater at 3A Composites, who described cladding which had been sold as fire resistant "burning like paper".

It was a "cheat", Geater concluded.

Arconic's UK sales manager, Deborah French, was asked at the inquiry: why not attach a health warning to the product?

"At the time," she said, the level of risk "wasn't so obvious".

7. Cladding sales continued, despite the risk

The company's UK sales manager, Deborah French, told the inquiry British buyers were more likely to request Reynobond PE and fit the cladding as "cassettes", the variant which resulted in poor fire tests, as they allowed for a "cleaner" appearance, with the fixings hidden from view.

In France, there was a move towards a "fire retardant" version, but not in Britain.

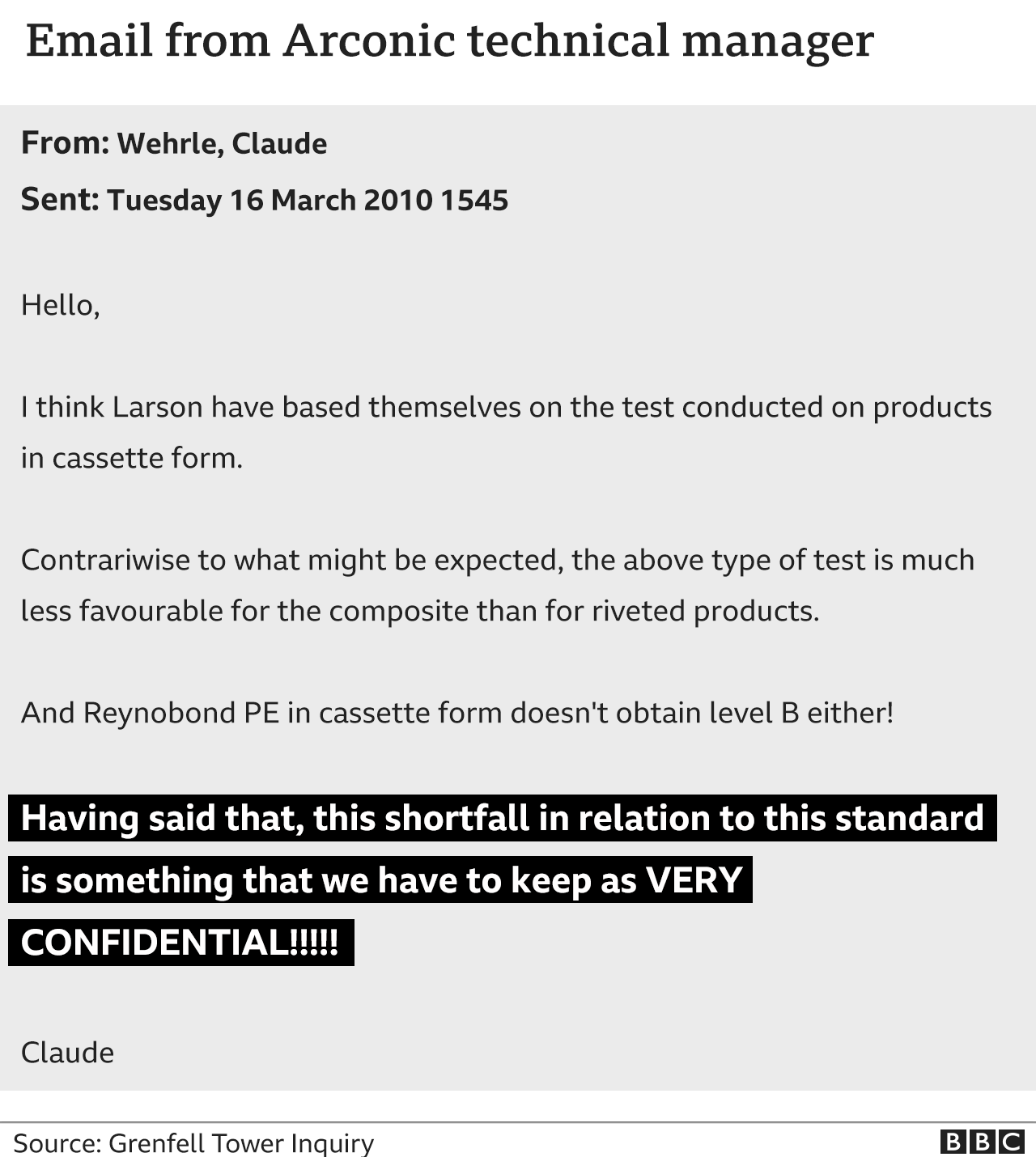

The company's technical manager Claude Wehrle, had been instrumental in commissioning the fire tests. He warned colleagues, and even some clients, about the results, even that they should be kept "very confidential", and sales continued.

In the minutes of a meeting in 2011, Mr Wehrle wrote that the cladding "has a bad behaviour exposed to fire", but, "we can still work with national regulations which are not as restrictive".

8. Arconic claimed it wasn't responsible for how its cladding was used

Since the fire, the company has stopped selling Reynobond PE. But it argues it is simply the manufacturer of a raw material, supplied to specialist "fabricators" who make cladding systems.

Arconic says it can't possibly know the end uses for its products, and it is for designers to check they could meet building regulations.

However, an email sent in May 2013 by sales manager Deborah French to a client gave a different impression.

She said the company could "control and understand" which type of cladding is being used in building projects because it only worked closely with a "very small group of approved fabricators".

"We are able to follow what type of project is being designed/developed," she wrote, and then offer "the right Reynobond specification".

Questioned about it, Ms French claimed she had not been telling the truth when writing the email.

9. The company knew it was selling to Grenfell

But, the inquiry has evidence Deborah French, who led the sale of cladding for Grenfell Tower, knew it was for a public residential building.

In January 2013, four years before the fire, she was sent "artistic renderings of what Grenfell Tower might look like" after completion of the work, according to her witness statement.

But she maintained throughout days of evidence that she had "no technical knowledge, and did not get involved in the design of projects".

After considering the night of the fire during the first phase of the Grenfell Tower inquiry, the focus switched in January 2020 with the hearings focusing on the refurbishment of the building in North Kensington and its role in the fire, and issues surrounding building regulations. This is still ongoing.

All episodes of the BBC's Grenfell Tower Inquiry podcast are available here.

Related topics

- Published18 February 2021

- Published9 February 2021

- Published10 February 2021

- Published17 February 2021

- Published5 April 2018