From books to Barbie, how letters to Santa evolved

The earliest letters are modest in their requests and by the 1970s children are listing the prices of what they want

- Published

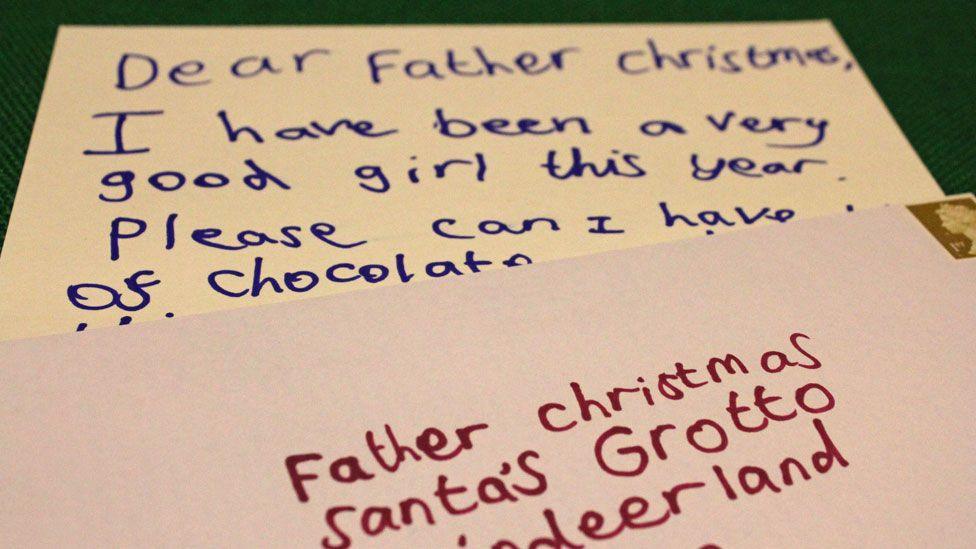

Sitting down to write a letter to Father Christmas is an annual ritual for children around the world.

It is a chance to say what sort of presents they would like in their Christmas Day stockings - but also how deserving they are of gifts after behaving beautifully all year.

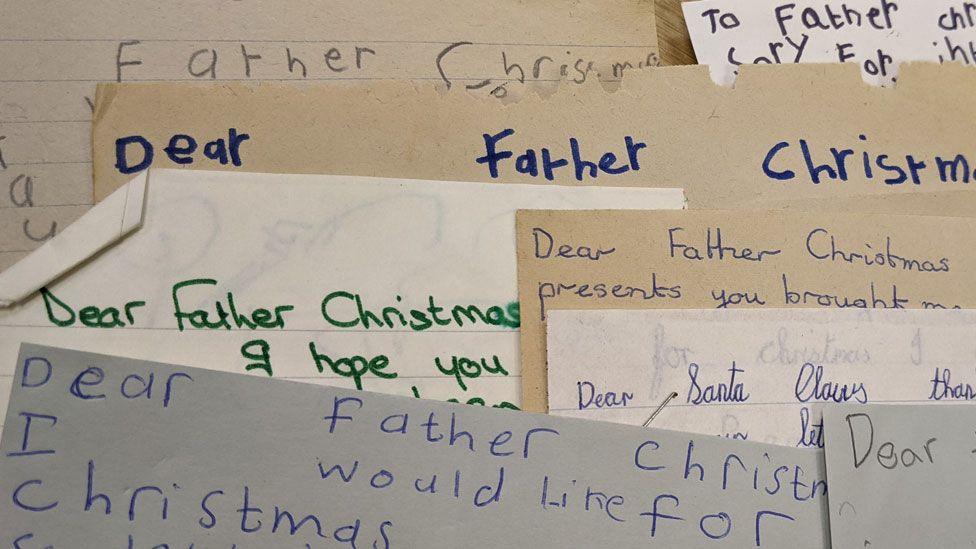

Dr Ceri Houlbrook, a lecturer in history and folklore at the University of Hertfordshire, has spent hours looking at thousands of children's letters which are held in archives across the country.

She said: "Children are so overlooked in social history, in how we talk about the past... [but] these letters by children are snapshots in time."

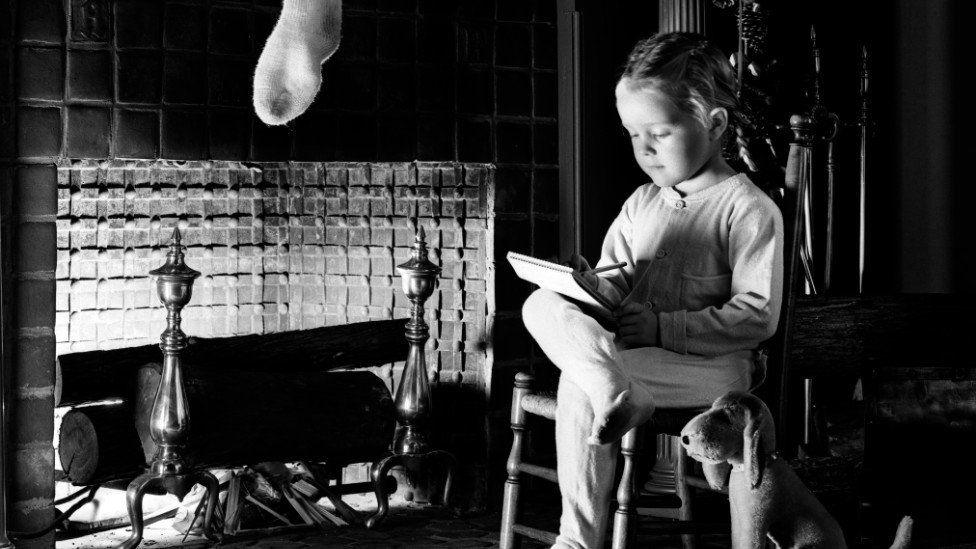

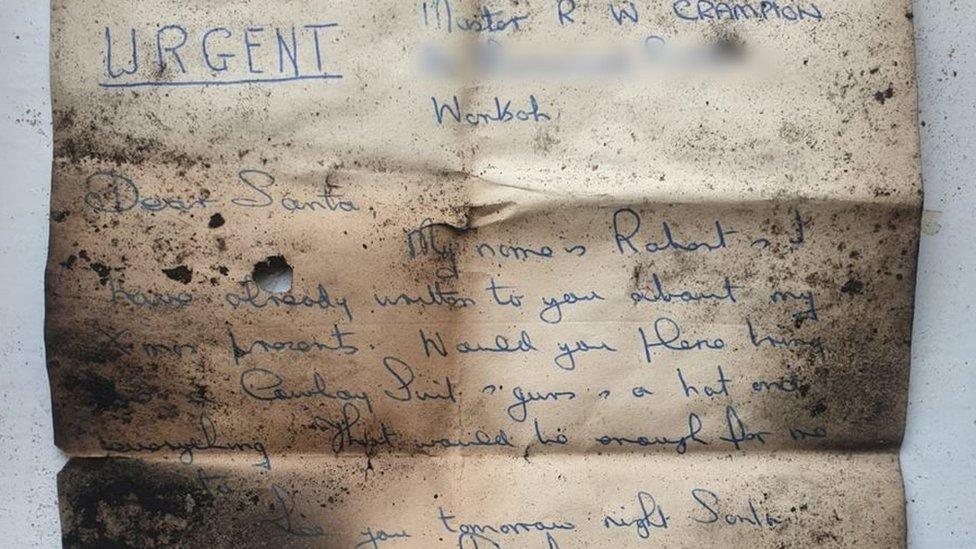

When the custom first began, children put their letters up chimneys, which was Father Christmas' traditional entrance

The idea for looking at the letters first came to Dr Houlbrook in 2018 and she has since visited a number of archives.

These include letters from the 1970s and 1980s, which were originally gathered by Sheffield City Council and are now held by Sheffield University because it was particularly interested in material from those decades.

More recently, she visited Leamington Spa Museum, in Warwickshire, which has collected letters written during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown "which felt more like diary entries, how bored the children were, how they can't wait to get back to school".

"In the early 20th Century, there's talk of how many letters to Father Christmas ended up in the Post Office's dead letter office, external, which is an office where the letters that don't have a real address are sent to - and then they just got destroyed, which is really, really tragic for a historian," she said.

She has also looked at digitised letters donated to the Post Office Museum in London.

So, how and why did the custom of writing letters to Father Christmas begin - and how has it changed?

As open fires gave way to central heating in the 1970s and 80s, children start to worry about how Santa can access the house and tell him where to find a key

"We don't know exactly, but it was probably at some point in the 19th Century," said Dr Houlbrook.

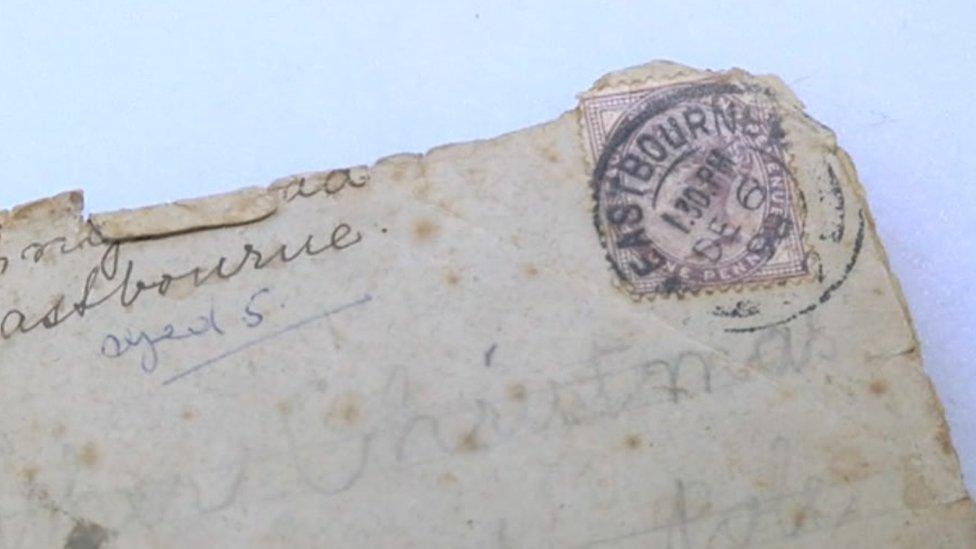

"We have newspaper articles that talk as if it's a given custom and we know about a few letters found in chimneys - children shoved them up the chimney, expecting some supernatural force to take them away."

At that time, literacy was on the rise with the introduction of compulsory education, and children also knew there was a reliable postal service.

Ceri Houlbrook said there are boxes of letters that have not been looked at since they were first gathered for archives

"By the end of the 19th Century, Father Christmas had a place and an address - he had the North Pole," Dr Houlbrook said.

"Mind you, there's a brilliant letter from the early 1900s that says, 'To the Post Office Manager, I don't know where Father Christmas lives, but please forward it on'.

"So there's the idea of a network and if you don't know where he is, the postmaster will."

'Girls asked for Sindy'

Sindy dolls were a must-have toy mentioned in many letters to Father Christmas by the 1970s

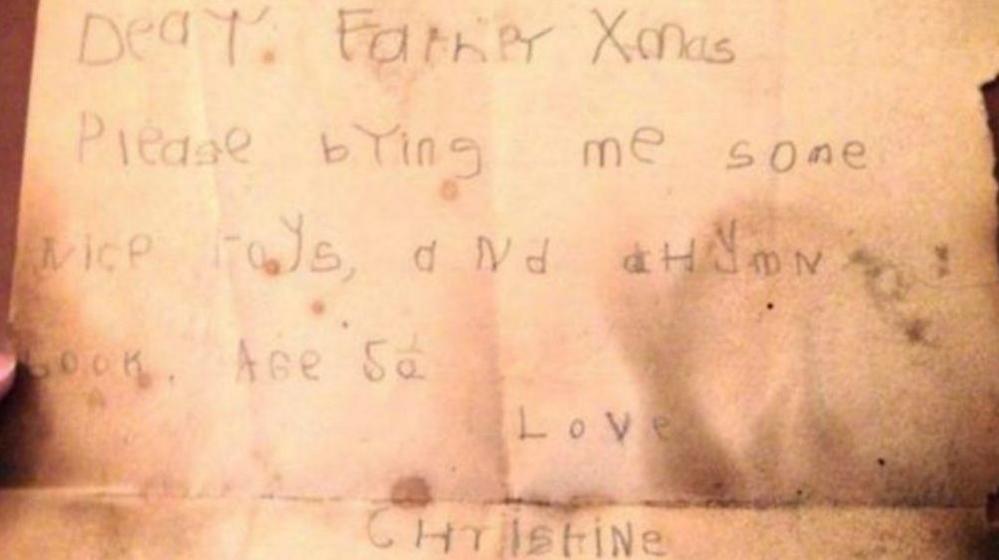

Dr Houlbrook said: "The earlier ones are much more modest in what they're asking for, one from the 1890s just asks for paints - that's it - another from the early 20th Century asks for a hymn book.

"By the 1970s, children start to provide quite long lists of requests - regularly with the retail price included or a catalogue page number."

Christine Churchill's 1930s' letter asking for toys and a hymn book was found in 2018 and she was later traced and spoke and spoke to BBC 5 Live

"Nearly every little girl in 1970s Sheffield was asking for a Sindy doll.

"By the 1980s, Barbie starts to creep in.

"Many more girls in the 1980s were asking for things like make-up and miniskirts, while in the 1970s it was the same as the boys - toys and books."

She added it was easy for people to misunderstand the letters as evidence children have become more greedy over the decades.

"But these are things that they want to play with, things they want to read and listen to - it's not all about stuff," said Dr Houlbrook.

'Beer and peanuts'

The letters are also transactional - children say they will leave out mince pies and sherry when Father Christmas leave the presents, said Dr Houlbrook

Another change is children have become far more curious, their letters are longer and they are keen to engage Father Christmas in conversation.

Dr Houlbrook said: "They're asking things like, 'How is Mrs Claus? I hope you're ready for Christmas' and warn, 'Be careful of the snow'.

"They're also talk about his folklore helpers - elves, pixies, fairies and angels - they've all got slightly different ideas of who is there helping Santa."

But the letters portray the children's awareness that they need to stay on Father Christmas' good side.

"So there's a huge amount of 'I've been really good this year', 'I've helped Nana', 'I've done my homework'," she said.

Dr Houlbrook also enjoys hearing adults' voices coming through.

"One of them made me laugh, saying, 'My daddy says that you actually prefer beer and peanuts' - and you could just imagine that child leaving beer and peanuts and the dad rubbing his hands together," she said.

'They give children a voice'

Dr Houlbrook said the letters are an "invaluable source for tracing change over time, giving an insight into children's lives and perspectives"

Inspired by the correspondence, Dr Houlbrook recently wrote Winter's Wishfall, a novel about an archivist delving into boxes of Dear Santa letters.

"I've not lost the magic of going to these archives - they're sweet and they're funny, the belief behind them is lovely - and they give children a voice," she said.

"Children are so overlooked in social history, in how we talk about the past, because there are so few documents from their perspective - the information we have about them does tend to come from adults.

"These letters by children are snapshots in time, when they sit down with pencil and paper, think about their lives, their year and why they deserve what they really, really want."

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Beds, Herts & Bucks?

Follow Beds, Herts and Bucks news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

- Published28 July 2021

- Published24 December 2020

- Published13 December 2018