London Eye at 25: The wheel that nearly wasn't

Watch: London Eye lifted into place

- Published

Were it not for the tenacity of two plucky London architects in the early 1990s and their unwavering vision, London's skyline - and the capital's New Year's Eve fireworks celebrations - would be significantly different today.

Julia Barfield and her late husband, David Marks, disregarded the fact they'd not won a competition to design a structure marking the new millennium and pushed on with their plans.

Securing press, public and financial support, the Millennium Wheel was eventually constructed.

On 9 March 2000, it took its first paying customers for a spin and 85 million people have since been on that journey.

"It's about celebrating London," says architect Julia Barfield who designed the London Eye

It's a perfect day to be high over the River Thames when I join Julia for yet another turn on the observation wheel now synonymous with the London skyline.

Neighbouring pods are filled with tourists taking pictures of the views across the capital, looking resplendent in the spring sunshine.

"We didn't want the landmark to be something that you just looked at," says Julia.

"It was something that would be participatory, it would be about celebration - and basically it's about celebrating London."

On a clear day, it is possible to see Windsor Castle from the London Eye capsules

In 1993, freshly qualified architects Julia and David entered a competition held by the Architecture Foundation and The Times newspaper to design a temporary structure to mark the new millennium.

They were not successful. In fact, none of the designs was very popular.

But undeterred, the couple continued their work on a 152m (500ft) observation wheel.

Julia wanted to build it, prominently, on the South Bank.

"We found this statistic: half a million people used to walk across Westminster Bridge, take a picture of the Houses of Parliament and then walk back north. The Southbank in 1993-94 was deserted."

It was an audacious proposal, very much in the spirit of the time: London, the forward-thinking, modern city, not just promoting its heritage but looking to the future.

"We were very, very sensitive that we were doing a larger object, in the centre of London, right next to a World Heritage Site, so we needed to make it as light as possible," says Julia.

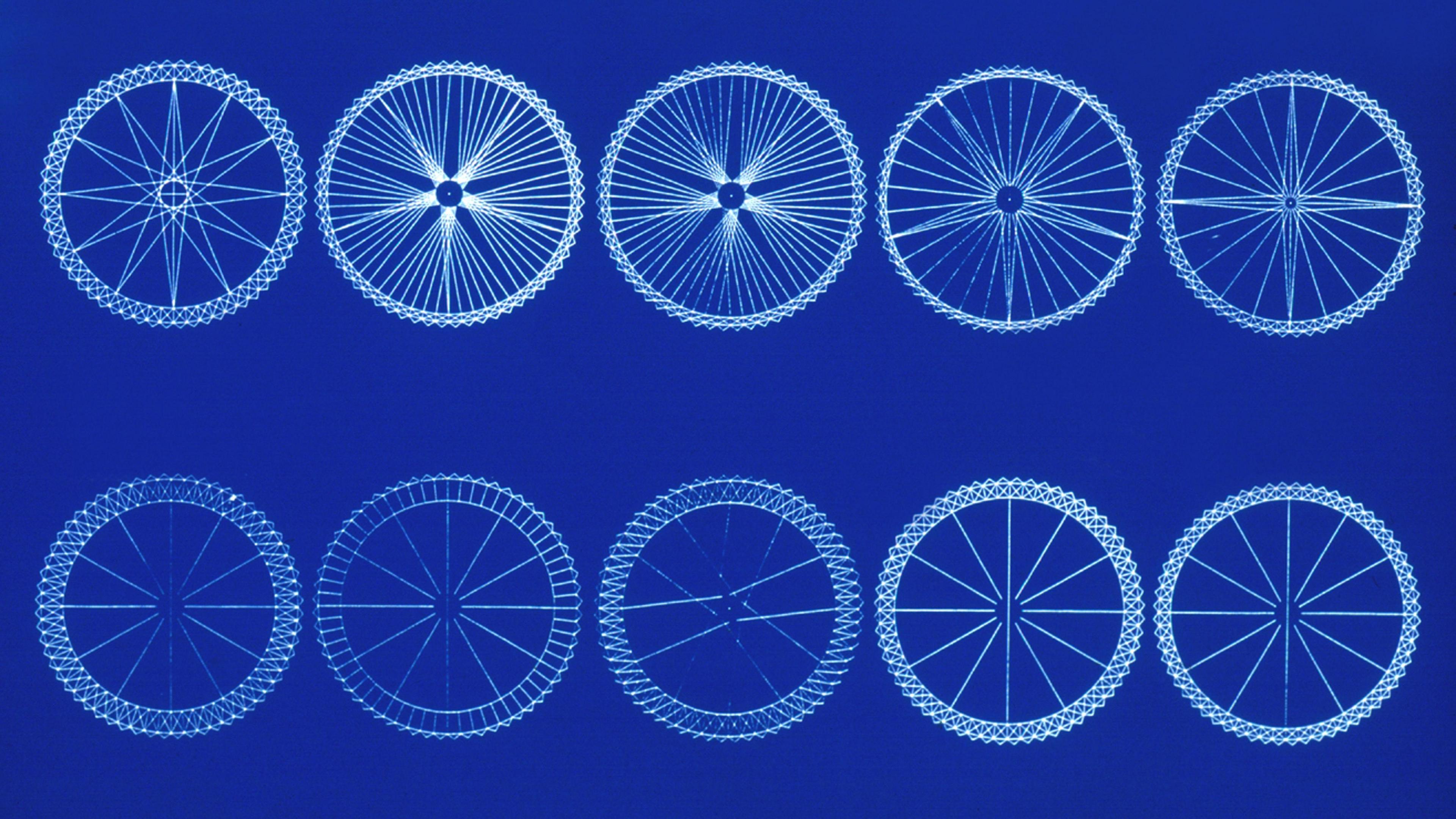

"The number of iterations that we went through, just in terms of the wheel, was at least a hundred."

CGI was still in its infancy in the early 90s but Marks Barfield created this picture of how the Millennium Wheel would look on the South Bank, as part of their bid to have it built

They came up with at least 100 variations for the wheel structure before settling on their final design

Julia and David set up The Millennium Wheel Company and invested in expensive new technology for their architecture practice, Marks Barfield.

They used computer-generated imagery (CGI) - very much in its infancy in the mid-90s - to show their wheel design set against views of London.

A journalist at London's Evening Standard newspaper came across their planning application and brought it to the attention of the paper's editor.

The Standard decided to support them and launched a "Back the Wheel" campaign.

Money soon followed, from British Airways.

The wheel was assembled before it was lifted into place

Even then, the project was nearly not realised. The first contractor insisted on cost-cutting changes to the capsules that did not fit with the architects' vision, reducing their design to a pastiche Ferris wheel.

"We would have been the laughing stock if we'd gone with capsules like that. So we killed the project for 24 hours."

A new company was found, the fabrication truly European: spindle from the Czech Republic, cables and curved glass from Italy, capsules from France, the main structure from the Netherlands.

Huge individual pieces were brought along the River Thames and assembled horizontally before a slow raising of the structure.

"When the wheel was only part way up, it was suspended at 35 degrees over the river at one point," recalls Julia.

"David and I went and sat at one of the benches across the river, very early in the morning and watched the sun rise. And it really looked like Boudicca was welcoming the London Eye on to the London skyline."

It took around a week to lift the cantilevered Millennium Wheel into a vertical position

The wheel at 35 degrees with Boudicca "welcoming the London Eye on to the London skyline"

And so, the London Eye, as it came to be known, took its place on the skyline - 135m (443ft) tall, with 32 capsules for people to ride in.

"At the beginning we actually had 60 capsules, being a real symbol of time: 60 minutes, 60 seconds," says Julia.

"But then we realised that would have been A, too expensive, but B, you'd have been looking into the capsule next door, rather than the view. So the symbolism worked but actually the experience didn't."

In the 25 years since it first opened to the public, there have been memorable moments: Mo Farah and his famous Olympic 'Mobot' pose atop a pod, 6,000 proposals - including Jim Branning to Dot Cotton in an EastEnders episode - and it regularly lights up in support of charities or campaigns such as Pride in London and the NHS turning 75.

And of course, each year it is the backdrop to the Mayor of London's New Year fireworks, seen across the world.

The London Eye is integral to London's New Year's Eve fireworks display, seen around the world

The Millennium Wheel, intended for just a year, now has a permanent place on the regenerated South Bank.

One per cent of ticket sales go to the local community, in perpetuity, and is spent on the open realm and given to local community groups and projects.

For Julia, the London Eye's legacy is the unfolding 360-degree view of London "like being on top of a mountain in the middle of the city".

It remains, she says, "a symbol of time turning, for the millennium - a circle with no beginning and no end. And it's a symbol of renewal and the cycles of life".

"The journey is as important as the arrival."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published8 May 2024

- Published20 March 2023

- Published31 December 2019

- Published13 August 2017