The 50-year-road to a British soldier standing trial for murder

- Published

Sunday 30 January 1972 was one of the most deadly – and consequential – days during three decades of conflict in Northern Ireland.

In the streets where it happened – the images of Bloody Sunday are painted on the walls and seared in people's minds.

A civil rights march was held on a wintry, sunny afternoon in Londonderry.

The demonstration was a protest against the policy of internment – imprisoning people without trial – which had been put in place following three years of violence.

REACTION: Soldier F's acquittal as it happened

ANALYSIS: Why did the judge acquit Soldier F?

THE STATE OF US: Soldier F not guilty

What happened on Bloody Sunday?

Soldiers from the Parachute Regiment shot dead 13 people in the Bogside area – which was, and still is, a strongly Irish nationalist community.

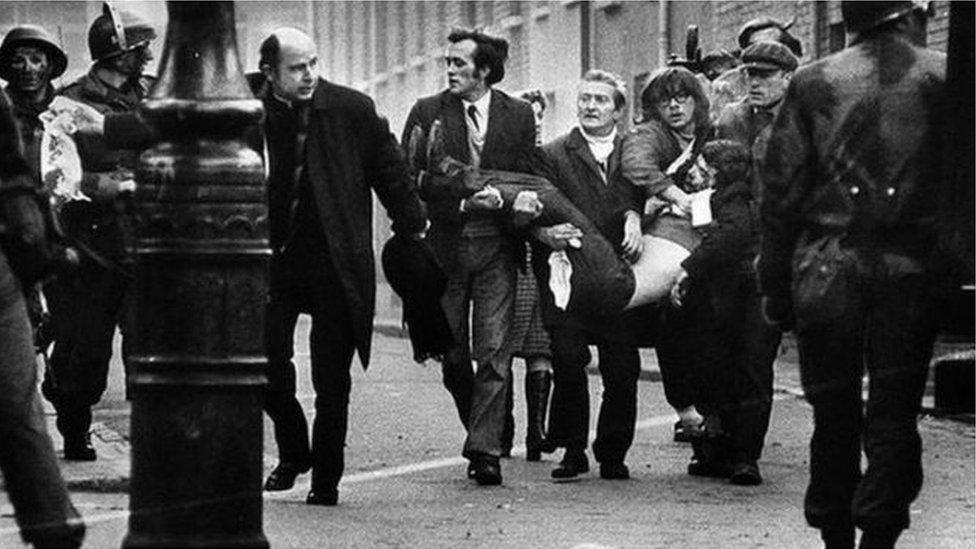

One image became particularly prominent.

Pictures showed a Catholic priest, Fr Edward Daly, waving a blood-stained white handkerchief as he tried to protect a group carrying a teenager, Jackie Duddy, who had been fatally wounded.

News camera operators captured much footage on the day.

The BBC archive features Fr Daly telling a reporter that soldiers "just seemed to fire in all directions" and he was "absolutely certain" that there was no provocation.

What investigations have taken place?

That version of what happened wasn't accepted by the initial investigation.

The Widgery Tribunal found the Army had been shot at first.

During the peace process, Tony Blair's government set up another inquiry, after campaigning by bereaved relatives, who said Widgery had been a whitewash.

In 2010, the report by Lord Saville said that on balance, the paratroopers had fired first and that none of the victims had posed any threat.

The then Prime Minister, David Cameron, apologised in the House of Commons – saying killings were "unjustified and unjustifiable".

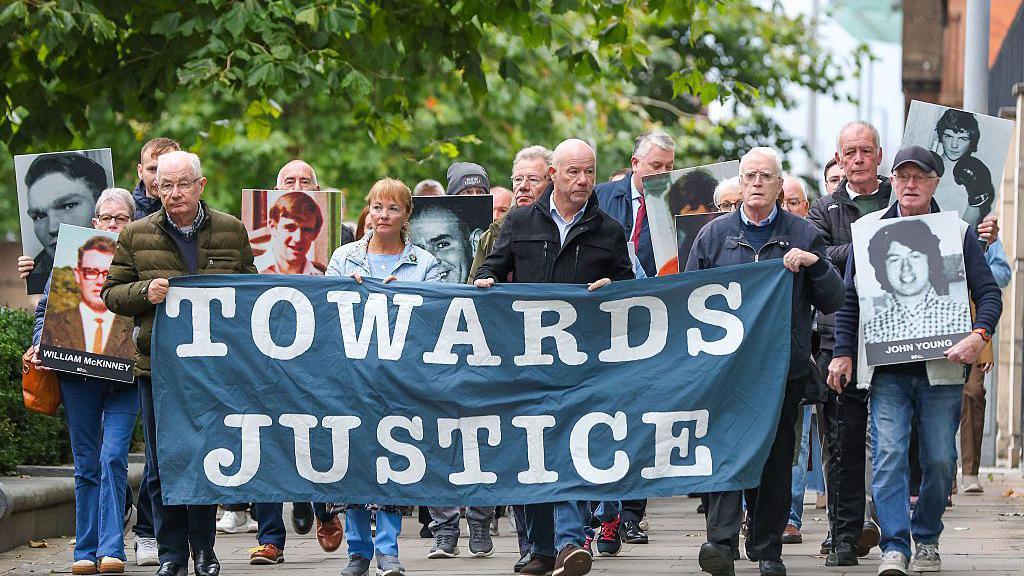

Families of the victims of the Bloody Sunday shootings march from the Bogside area of Londonderry to the Guildhall holding photographs of their relatives to get a preview of the Saville Report in 2010

The police began to investigate.

One former paratrooper, known as Soldier F, was prosecuted for murder.

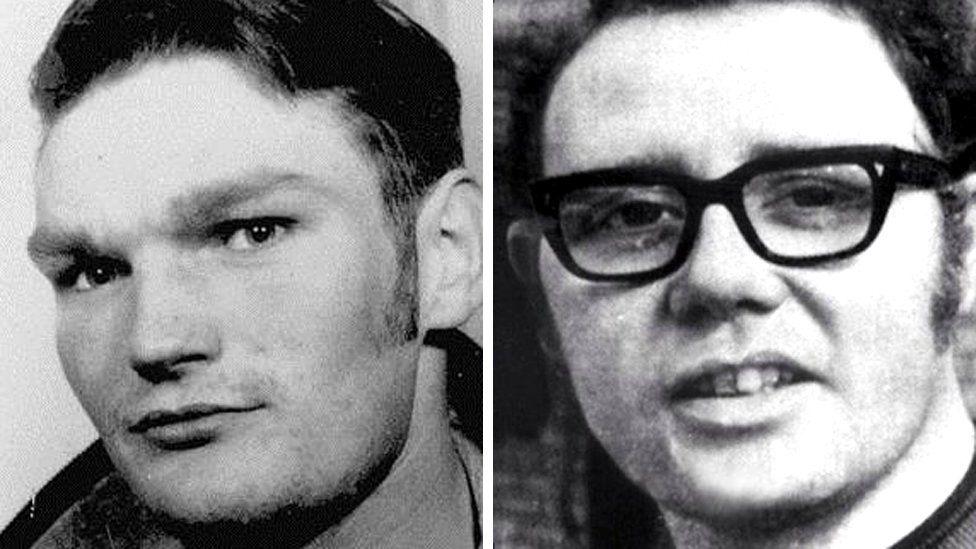

He was charged over the killings of James Wray, 22, and 26-year-old William McKinney.

Soldier F was also accused of attempting to murder Patrick O'Donnell, Joseph Friel, Joe Mahon, Michael Quinn, and an unknown person.

There is a legal order preserving the veteran's anonymity, which his lawyers have argued is necessary because he is at risk of attack.

He told the Saville Inquiry that he had only fired at people who were armed.

That claim was rejected in the final report.

Material from the inquiry could not be used directly as evidence in the criminal process.

In the dock, the veteran was screened from view behind a blue curtain.

He spoke for the first time in court at a hearing in December 2024, to reply "not guilty" when the charges were put to him.

What have the relatives said?

Family members and supporters of those killed on Bloody Sunday hold a banner and photos of those killed as they walk to Belfast Crown Court on 16 October 2025 for the trial of Soldier F

Relatives of those who were killed on Bloody Sunday travelled from Derry to Belfast Crown Court each day of the trial.

John Kelly, whose brother Michael was killed, said they always knew that listening to the proceedings would be painful.

"I can see everything in my mind's eye," John said, as we walked around the main locations mentioned in the trial – from Rossville Street, where Michael was shot dead, to the adjoining Glenfada Park, where James Wray and William McKinney were killed.

"It even takes me back to where I was that day.

"I helped to carry Michael and place him in the ambulance.

"I relived every moment during the evidence.

"But even with having to go through all that – it's still worthwhile for me."

James Wray (left) and William McKinney (right) were among those who were killed on Bloody Sunday

Bereaved families had to fight a separate court case to make the trial go ahead.

In 2022, they won a legal challenge against a move by crown lawyers to drop the prosecution of Soldier F.

Prosecutors had been concerned that key evidence would not be usable in court.

What did the veterans' commissioner say?

On the first day of the trial, the Northern Ireland veterans' commissioner suggested that prosecutions of military personnel indicated an imbalanced approach to investigations into killings from the years known as the Troubles.

Outside the court gates, David Johnstone told the media: "There are many families of soldiers across Northern Ireland and Great Britain who have never had the truth regarding the loss of their loved one, or the opportunity of justice."

He pointed out that more than 1,000 members of the security forces had been killed during the conflict, adding: "The vast majority of the 300,000 armed forces who served in Northern Ireland did so with restraint, dignity and professionalism."

What happened at the trial?

The trial was held in front of a judge only, as is standard practice in Northern Ireland for cases from the Troubles.

Joe Mahon, Joseph Friel and Michael Quinn were among the witnesses who gave evidence in person.

The accounts of other civilians were given through statements, which prosecution barristers read to the court.

A number of witnesses told how they tried to escape from intense shooting on Rossville Street by going into Glenfada Park, which is a courtyard.

But they came under fire there too, with several describing how they were shot when running away, and tried to protect themselves by lying still on the ground and pretending to be dead.

However, the only evidence which specifically said that Soldier F fired his rifle in Glenfada Park came in the form of statements from two other paratroopers, known as Soldiers G and H.

The statements were made in 1972 to the initial investigation by the Royal Military Police, and then to the Widgery Inquiry.

They said they fired shots along with Soldier F.

A mural commemorating the victims of the 1972 Bloody Sunday killings in the Bogside area of Londonderry

Soldier G has died, while Soldier H indicated he would not testify in the trial, and would use his legal protection against self-incrimination.

Defence lawyers argued that the key prosecution evidence was "fundamentally inconsistent" and was not backed up by the civilians' accounts.

On that basis, they applied to have the case dismissed.

The judge did not grant that application – but the defence continued to present the issues around the soldiers' statements as a major reason why the judge should acquit Soldier F.

The veteran himself did not testify.

His lawyer read into the record a statement which the accused gave to police – in which Soldier F said he was "sure" that he "discharged his duties", but he would not be answering questions because he no longer had "any reliable recollection" of events.

John Kelly, whose brother Michael was shot dead on Bloody Sunday, is pictured in the Museum of Free Derry in 2022

Glenfada Park is now the site of the Museum of Free Derry.

On its exterior wall, there is a patch of perspex, which preserves the circular bullet marks from Bloody Sunday.

Inside, James Wray's jacket is on display, its shoulder torn by the shots which killed him.

On a shelf in the same cabinet is a camera which William McKinney was carrying when he was shot dead.

Many historians say the killings inflamed the unrest in Northern Ireland.

After 53 years of grief, controversy and campaigning, the criminal process has ended with no conviction.