Call to recognise Napoleon's nephew as Gaelic studies 'pioneer'

Louis Lucien Bonaparte toured Scotland in 1858

- Published

A Gaelic scholar has called for greater recognition of the contribution a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte made to the study of the language.

Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte travelled through Scotland in 1858 gathering information on Gaelic, and also Scots.

Rob Ó Maolalaigh, professor of Gaelic at the University of Glasgow, said Bonaparte had been a pioneer because of his early use of fieldwork to study languages.

He visited a Gaelic chapel in Perth and attended a sermon in Kilmallie in Lochaber to hear Gaelic being spoken.

His uncle Napoleon was one of history's greatest military commanders - winning battles across Europe - and emperor of France.

His French army was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 by a coalition force, which included British, Dutch, German and Prussian soldiers.

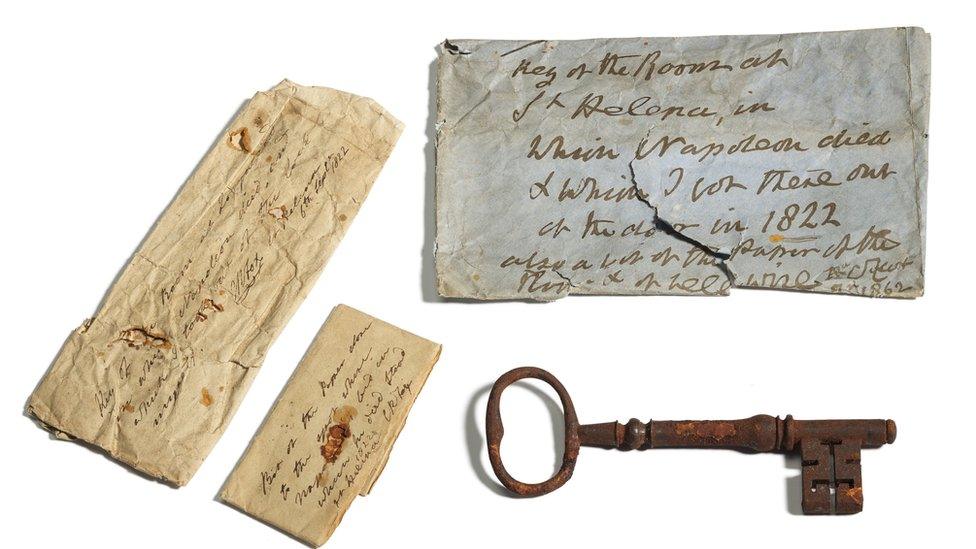

Napoleon surrendered and was exiled to St Helena, an island in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

Napoleon was emperor of France

His nephew Louis Lucien was a philologist, a person who studies the history of languages.

Prof Ó Maolalaigh said the prince was celebrated in Wales for his research on Welsh, but was almost unknown in Scotland.

He toured Scotland in 1858, visiting his Gaelic and Scots language contacts. They included church ministers.

Prof Ó Maolalaigh said the prince travelled incognito, the wider public unaware of who he was. His tour took him to Shetland and newspaper accounts suggest that he also visited Orkney and the Hebrides.

Read Ruairidh Maciver's story on BBC Naidheachdan

- Published8 January 2024

In Inverness, Louis Lucien sought Gaelic translations of Biblical texts and later attended a sermon given by a Rev Archibald Clark in Kilmallie.

Prof Ó Maolalaigh said: "He was clearly interested in the sounds and acquiring some sort of fluency in the language.

"He was a pioneer in putting emphasis on fieldwork and actually speaking to native speakers, and not just relying on the written word. He was ahead of his time.

"I think that does deserve to be recorded in history."

The prince's fluency in Gaelic is not known, with some accounts claiming he was very fluent.

"I think the truth is somewhere in the middle," said Prof Ó Maolalaigh.

Related topics

- Published1 December 2023

- Published22 September 2023

- Published14 January 2021