The 5,000 letters of hope sent to woman during WW2

Hope Robinson's husband was a prisoner of war in Thailand, working on the Burma Railway

- Published

During World War Two, a young mother in search of information about her husband trapped in a prisoner of war camp in Thailand did something - thought to be against the wishes of the War Office - which saw 5,000 letters of thanks and hope delivered to her.

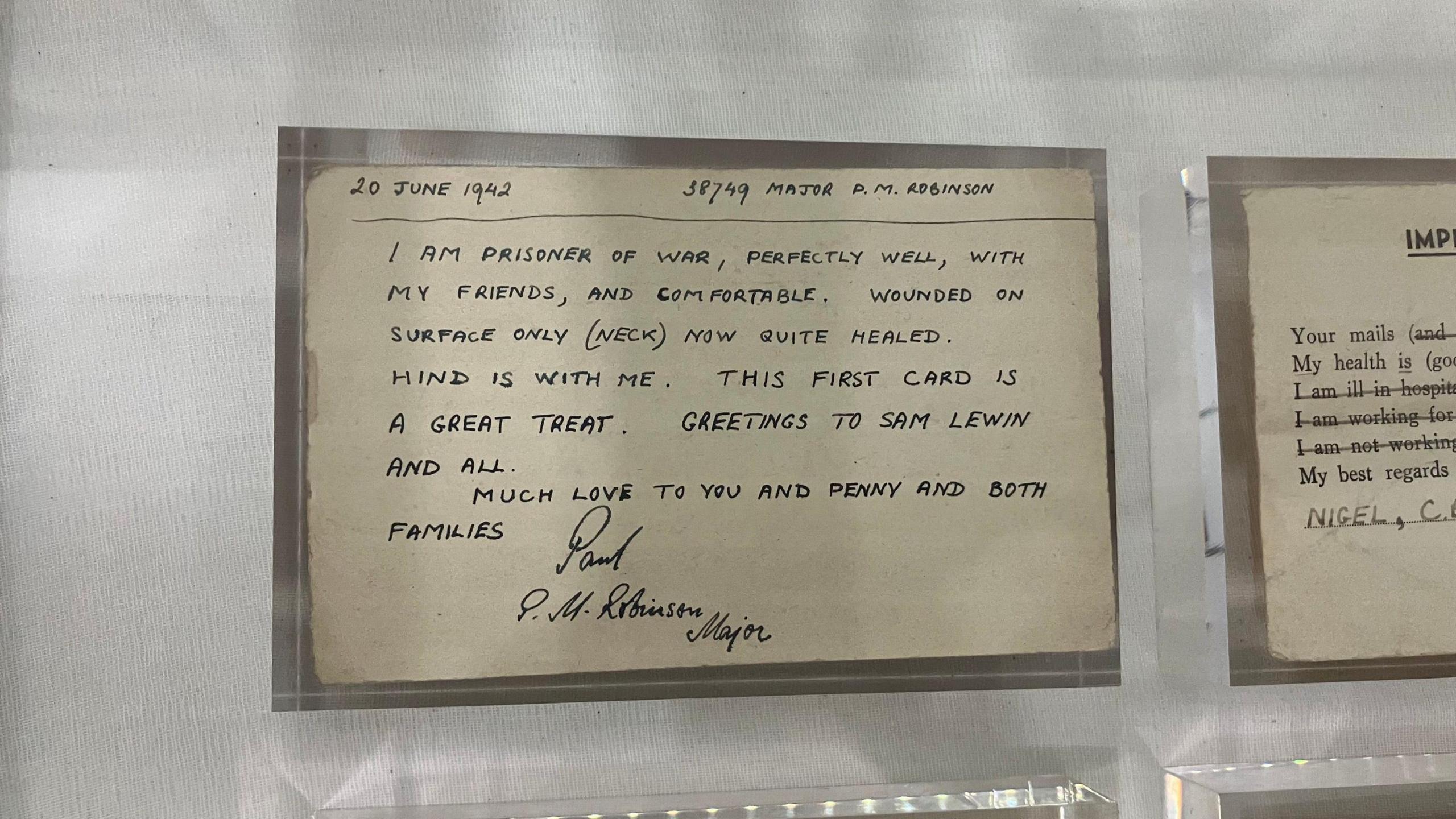

Hope Robinson's husband was an officer in the British Army who was captured by the Japanese in Singapore in February 1942, and kept as a prisoner on the Burma Railway.

In November 1944, two soldiers who had lived in the same camp as her husband, Major Paul Robinson, arrived home after escaping captivity.

Mrs Robinson, from Ilkeston, in Derbyshire, turned up on the doorstep of one of the men the day he returned, interviewed him, and produced a pamphlet about life in the camp.

Hope Robinson's daughter Penny Aldred said paper was rationed, so it was difficult sending the leaflet out

Titled “Life as a Prisoner of War in Thailand”, she wrote about medical conditions, food - each man got one pint of rice per meal - and how the men went without new boots for a year and new clothing was limited.

But morale was "excellent", she wrote, and the men believed they were going to be freed.

She wrote to the Sunday Express with brief details about her findings, asking people to get in touch with a stamped address envelope if they would like a copy of her leaflet.

The next day her daughter Penny Aldred, who was seven at the time, remembers "huge sacks of letters" arriving.

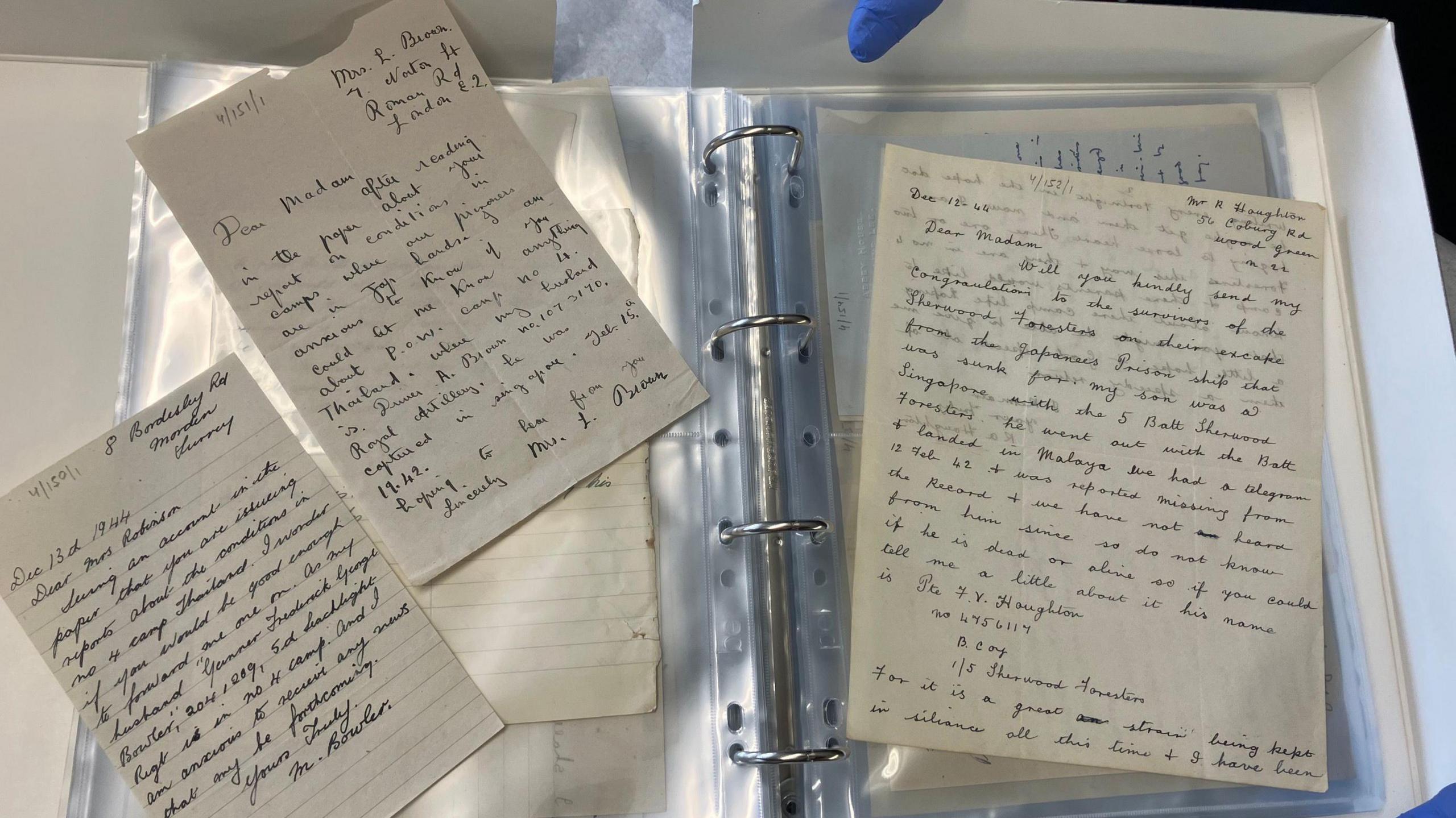

They were from families - mainly mothers and wives - across the country, as well as America and Ireland.

In total more than 5,000 were delivered to their door.

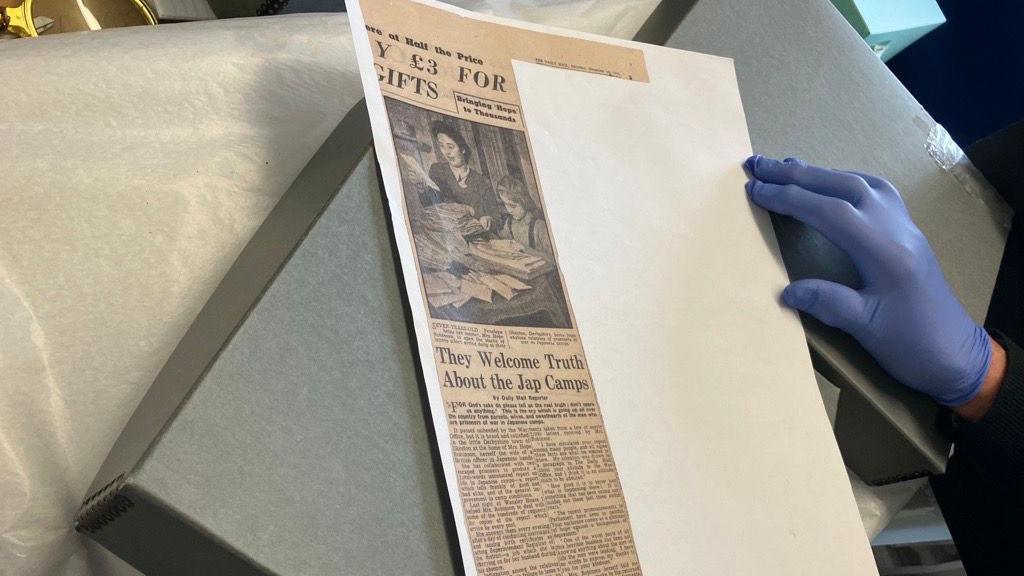

Mrs Aldred and her mother were photographed opening letters, and appeared in the Daily Mail

Mrs Aldred said: "Thousands of letters started to come. She had to get people to help her open them.

"Paper was rationed, so it was very difficult to get the information printed and sent out.

"She got some help from local people who managed to get supplies of paper.

"Then the Daily Mail found out and came over, and photographed me opening one of the letters."

The 86-year-old said "nobody had heard anything" for months and months after their loved ones had been captured.

So the letters were "the case of 'what can you tell me about what they must be going through?'"

Mrs Aldred said in later years it had "gradually dawned on me what an extraordinary thing my mother was doing".

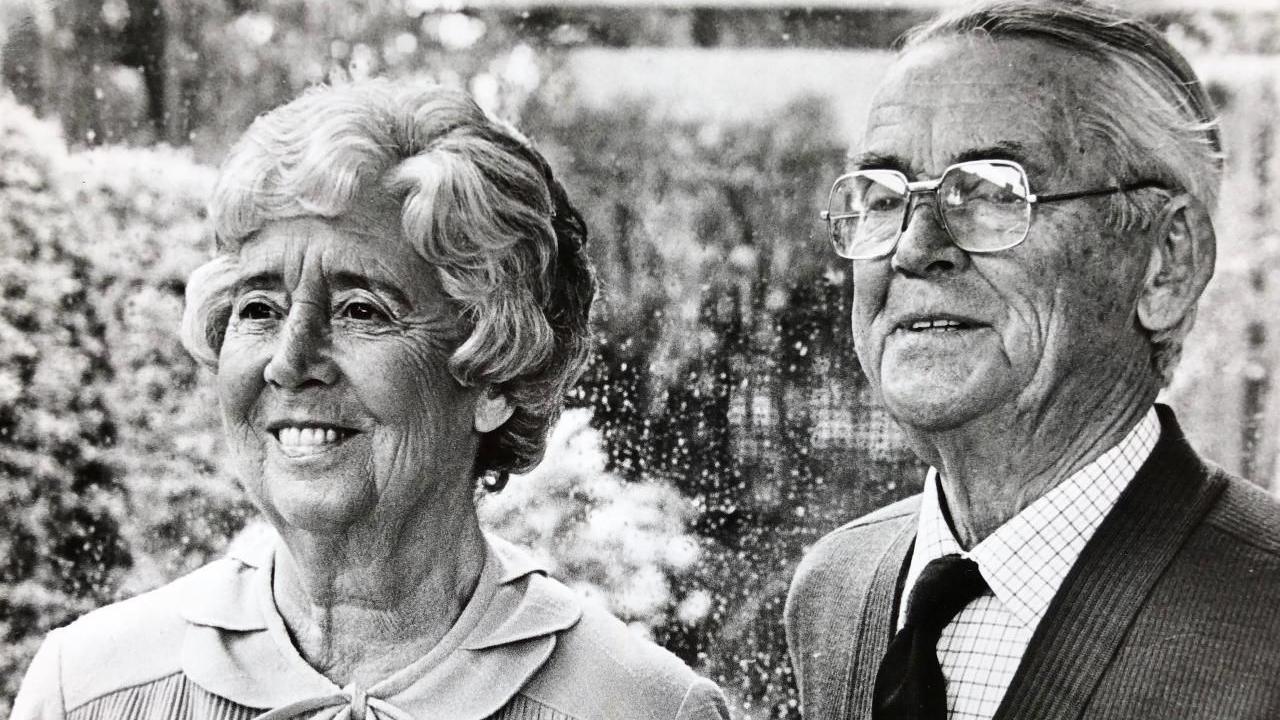

Mr and Mrs Robinson met at a 21st birthday party, and married in 1936

The grandmother-of-four added she found more than 2,000 of the letters in the loft of her parents' home in 2015.

She said: "Everything was cleared out of the house, and I went up to the attic. I found a bundle of letters.

"I thought these would be quite interesting...I didn't realise how exceedingly interesting they would be."

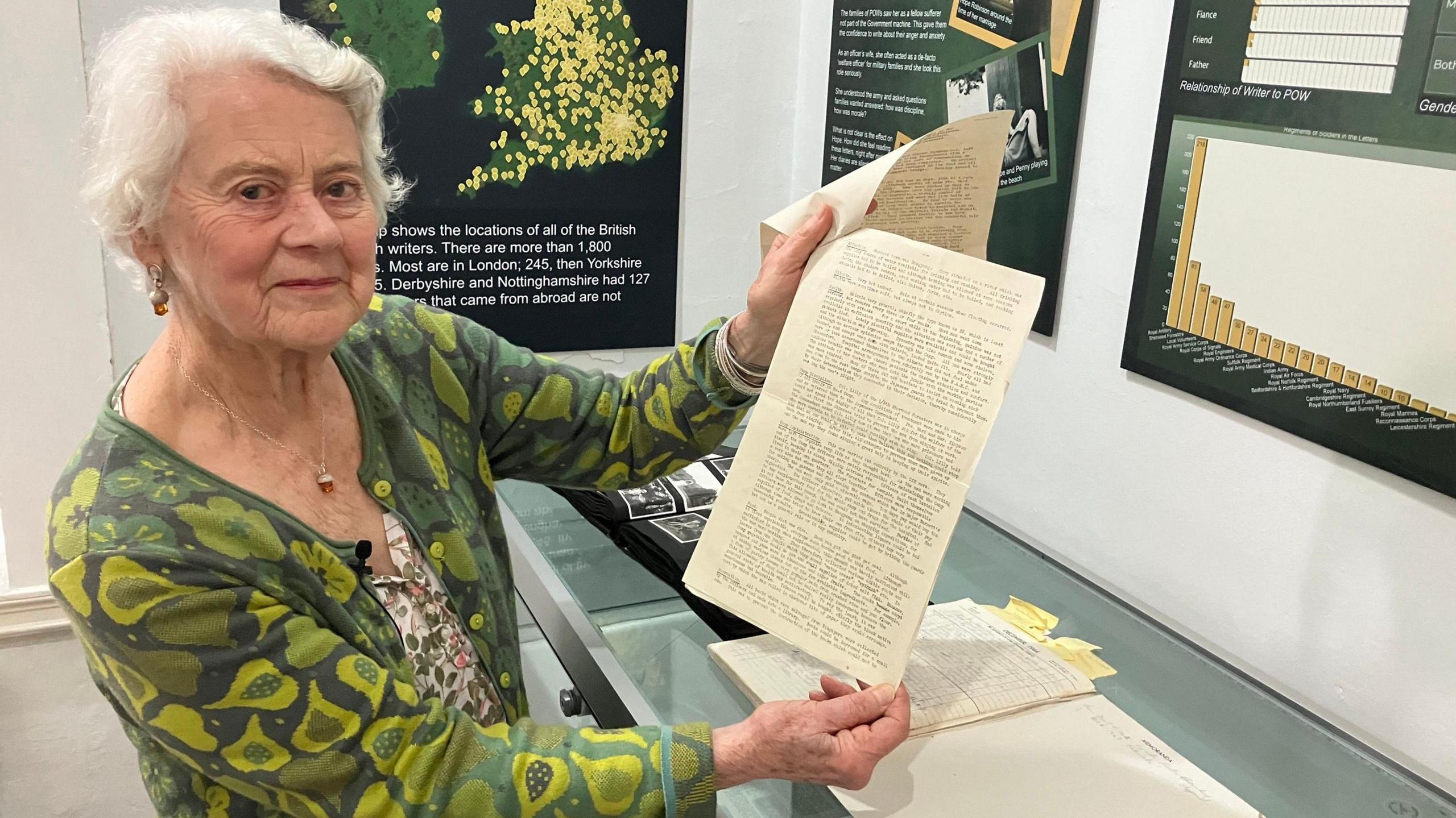

Mrs Aldred donated them to Erewash Museum, in Ilkeston, where there is a permanent exhibition about the letters.

On Friday, a Hope Robinson day took place as part of a series of events ahead of the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

More than 2,000 of the letters are kept at Erewash Museum

Keith Oseman, lead volunteer researcher on the letters, said they were "a remarkable document of the thoughts and feelings of the people back home waiting to hear from the prisoners in the Far East."

He added: "When Hope published her leaflet and her representation of that in the newspapers, people jumped on it.

"Along the way, they started to pour their hearts out to her."

The researcher said he believed publishing the pamphlet was against the wishes of the War Office.

He added: "We don't have any hard evidence that they threatened her, except in a later letter where she said a Colonel asked her not to publish.

"She said 'I need to do it to cheer up people like me'."

Mr Oseman said nearly 70% of the writers of the letters were women, mainly mothers and wives

Mrs Robinson also kept a diary during the war, where Mr Oseman said she wrote about the morning the men marched away to what turned out to be Singapore and captivity.

He said the diary recounted how her husband had left a simple letter in her pyjamas, which read "bless you, my darling".

Mr Oseman said they were two young people with a young daughter, who were clearly in love.

"They had to stop their lives, and he had to march away. Nobody knew what would become of him and if he would ever come back."

Mrs Aldred said her mother's diary was written for her father - who was in The Sherwood Foresters regiment - and finished on Victory in Japan day, 15 August 1945.

She said: "In the diaries, every year when it was my father's birthday, I insisted on having a birthday cake and a party and singing happy birthday to daddy."

Mrs Aldred said: "We didn't hear anything for nearly a year. We had five postcards altogether"

After the war, at the end of September 1945, her father returned home.

Mrs Aldred said: "I can remember him coming around the back entrance of the house and I was running round to meet him.

"He caught me up in his arms.

"Of course, I didn't realise the seriousness of it all."

She said: "As time goes on, I realise the true horror for my mother."

Mrs Aldred said: "Although he was very thin... he went back to the office straight away.

"Life carried on, and he didn't talk about it much."

Hope and Paul Robinson lived the rest of their lives together in Ilkeston

In 1947, Mrs Aldred's sister Victoria was born.

Major Robinson lived to the age of 87 before he died in 1997 in the same house he was born in. Mrs Robinson outlived him and died in 2008, aged 93.

Mrs Aldred said: "I was always told he would be coming home when the war ended - and he did."

Follow BBC Derby on Facebook, external, on X, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external or via WhatsApp, external on 0808 100 2210.

Related topics

- Published1 June 2024

- Published14 October 2023

- Published28 May 2024