'My dad nearly died on D-Day - in Essex'

Paul and James Roberson pictured in the early 1970s

- Published

On the day troops from Britain, the US and Canada were landing on beaches in northern France during World War Two, a secret military unit somehow managed to escape with their lives during a self-inflicted rocket onslaught - in Essex.

Eighty years on from Paul Roberson's "incredibly lucky escape" in Shoeburyness on 6 June 1944 - otherwise known as D-Day - James Roberson, 70, has been telling the story of the bizarre incident in which an accidental discharge somehow failed to cause serious injury.

In 1942 his father Paul, who lived in Barnes in south-west London but grew up north of the River Thames in Edgware and Kilburn, had joined the Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development - a part of the Royal Navy known colloquially as the "wheezers and dodgers".

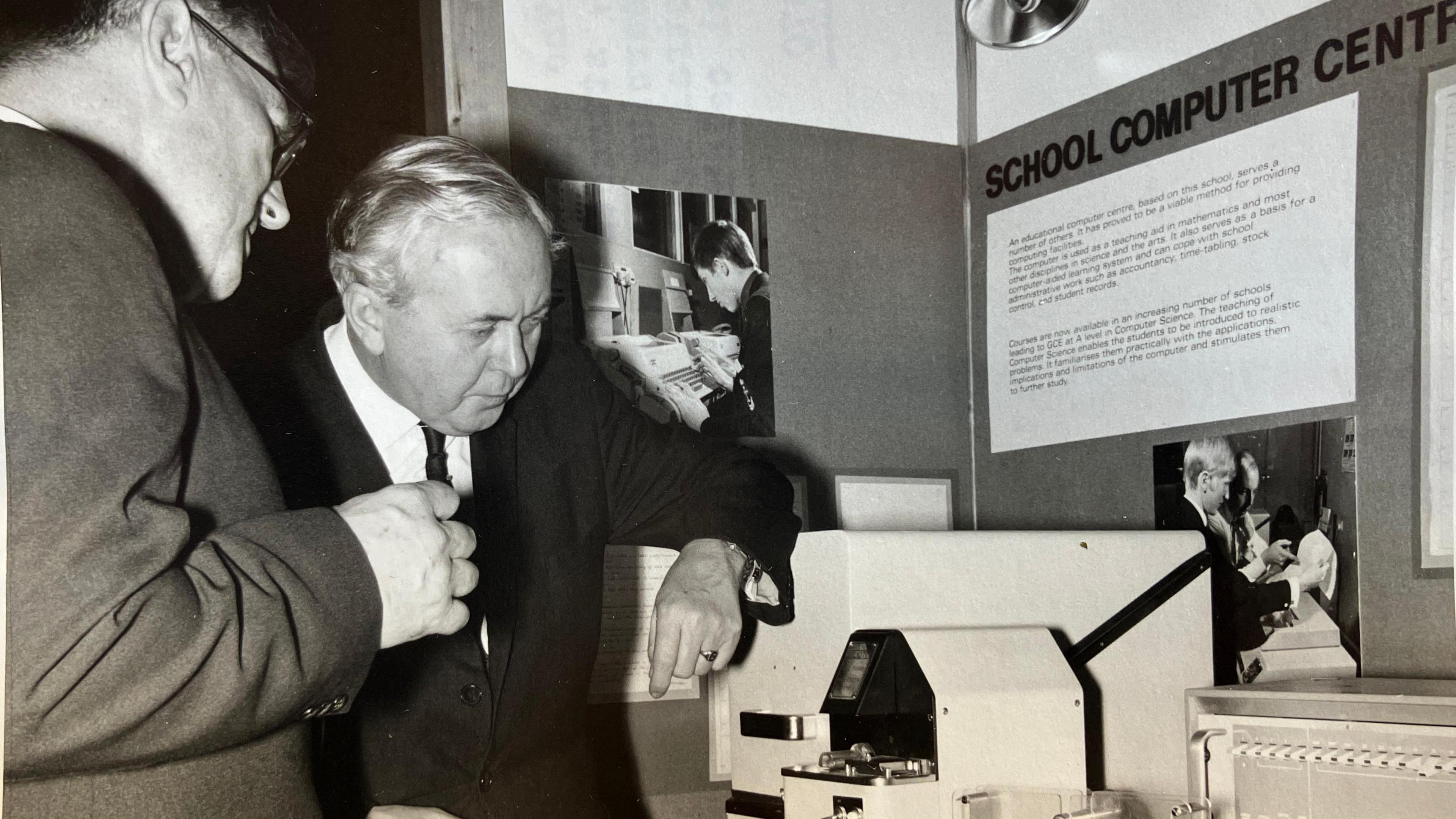

Paul Roberson with former prime minister Harold Wilson

Much of the unit's work was detailed in Paul Roberson's PhD thesis, which was kept secret for years - although the wheezers and dodgers were later written about by the author Gerald Pawle.

One account describes Roberson's team working on kites and “magic” balloons, radar, fast aerial mines, bombs to blow holes in the Atlantic Wall, radio-controlled boats and other extraordinary inventions.

A success was the development of a pigeon parachute to help deliver homing pigeons behind enemy lines. (About 30 pigeons would go on to be awarded the Dickin Medal - often described as the Victoria Cross for animals.)

Paul Robseron (left) with two colleagues

One member of the secret unit, Prof Jim Jeffes, told the BBC in 2004 that they were not "a gang of crazy scientists".

He said: "It was a hardworking, productive collection of people who were extremely well-motivated."

In 1944, Roberson and his colleagues were based at a military establishment in Southend-on-Sea in Essex.

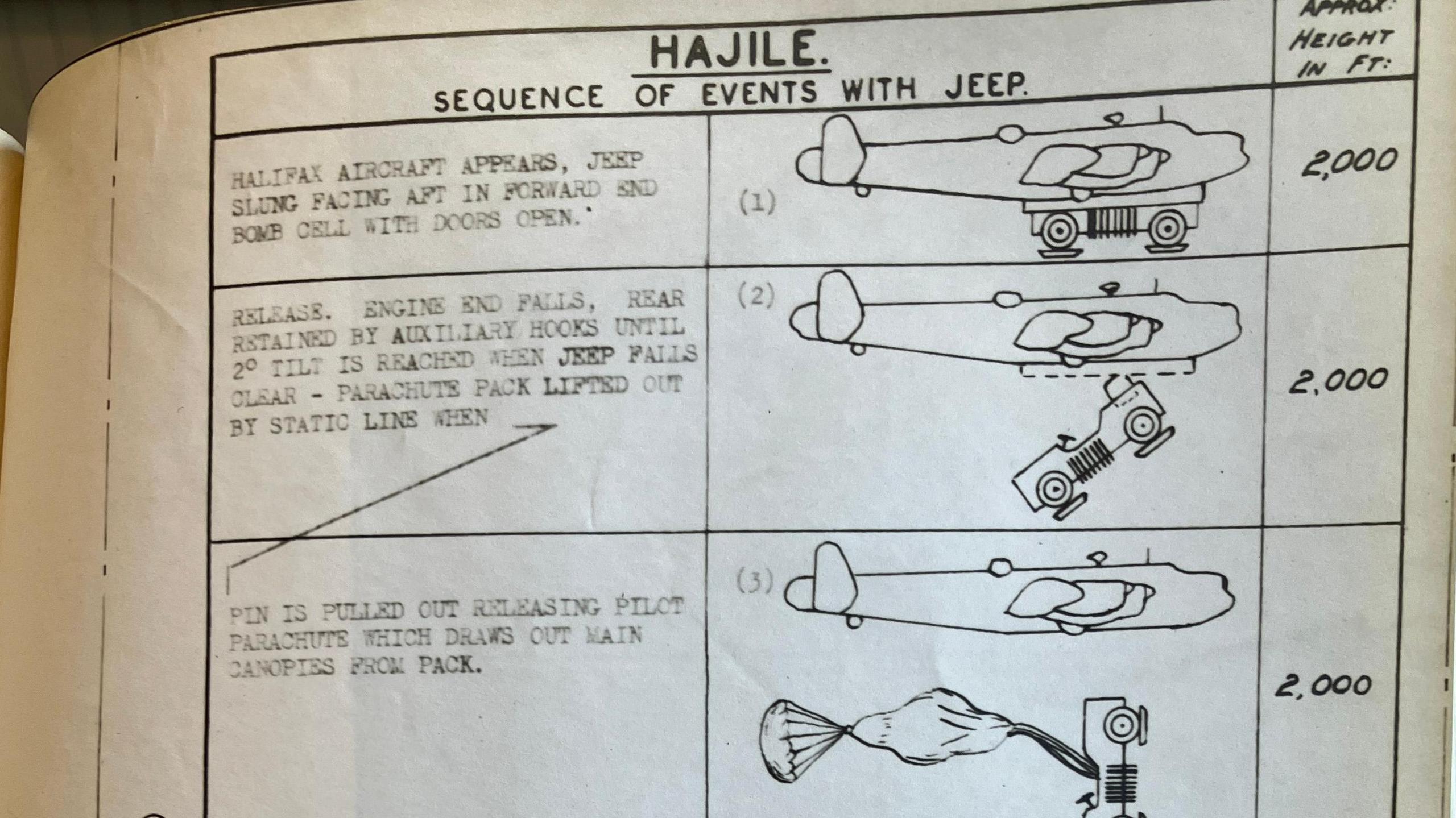

One of their projects was known as Hajile (Elijah spelt backwards), which they were working on while the largest military operation on sea, air and land ever attempted was taking place.

Speaking to BBC London a stone's throw from Admiralty Arch, near Trafalgar Square, James Roberson said of Hajile: "It was a mechanism to drop jeeps or light tanks or other, relatively heavy, objects out of a plane but with a small parachute on the top so that it dropped accurately and didn't drift.

"Then 15ft (4.5m) above the ground, there was a mechanism where rockets would fire and the object would come gently to the ground in a cloud of smoke, and that was the plan.

"It didn't quite work out that way."

Diagrams show the plans for Hajile

Mr Roberson said: "My dad was standing in a circle of these rockets just fiddling around, trying to get the connections right, and in a block house not far away there was another technician and he obviously thought, 'Oh, I wonder if this circuit works?'

"He clicked a switch and, at that point, he fired all the rockets and the rockets fired around my dad, half drilling him down into the ground, and this enormous apparatus shot up 40ft (12m) into the air and flew around.

"Everybody was blinded by dust. They were wandering around and then the rockets finished and they crashed back to earth.

"Incredibly, none of them were killed or injured. It's a miracle that nobody was hurt.

"My dad nearly died on D-Day - but in Shoeburyness, not on the beaches of Normandy."

The man who prepared France for D-Day

- Published4 June 2014

The German soldier 'liberated' by D-Day

- Published7 June 2014

The piece of paper that fooled Hitler

- Published27 January 2011

Mr Roberson, who spent many years working for BBC's East Midlands today, said he wanted to tell the story "because I'm 70 now... I'm not sure I'll be around in another 10 years".

He added: "It seems to be a completely forgotten branch of the navy and of the British armed forces."

James Roberson reporting for the BBC in 2010

The former journalist remains baffled as to why so little is still known by the wider public about a unit he says "had a tremendous amount of success and did amazing work".

He added: "There just doesn't seem to have been the sort of appetite for it.

"Maybe they were just very modest."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external