How Jodrell Bank spied on Soviet missile launches

The dish picked up radio signals from missile launches thousands of miles away

- Published

The secret Cold War role played by a giant radio telescope in the middle of the Cheshire countryside has been revealed.

Jodrell Bank Observatory monitored Soviet missiles as nuclear tensions between the USSR and Nato powers escalated in the 1960s.

David Abrutat is the official historian for Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), which provides top-secret intelligence to ministers and the armed forces.

He told BBC Radio 4's Archive On 4 programme that only the pioneering radio astronomer - the late Sir Bernard Lovell - and two other Jodrell Bank employees were aware of the work being done there by GCHQ staff, who were nicknamed the "secret squirrels" by others working at the site.

Mr Abrutat said British and American intelligence bosses needed to know more about the Soviet missile programmes.

"A lot of these early space probes that were launched, the early satellites that were launched by the Soviet Union, relied on intercontinental ballistic missiles," he said.

"You could get an understanding of telemetry (the process of recording and transmitting instruments' readings) - the power, the capability of the missile systems being used - by monitoring a space launch.

"There was intelligence dividends from us being involved in this space programme and the work of Jodrell Bank."

He said it gave the UK "a capability" which is did not previously have.

Sir Bernard Lovell faced the sack until he managed to eavesdrop on Sputnik

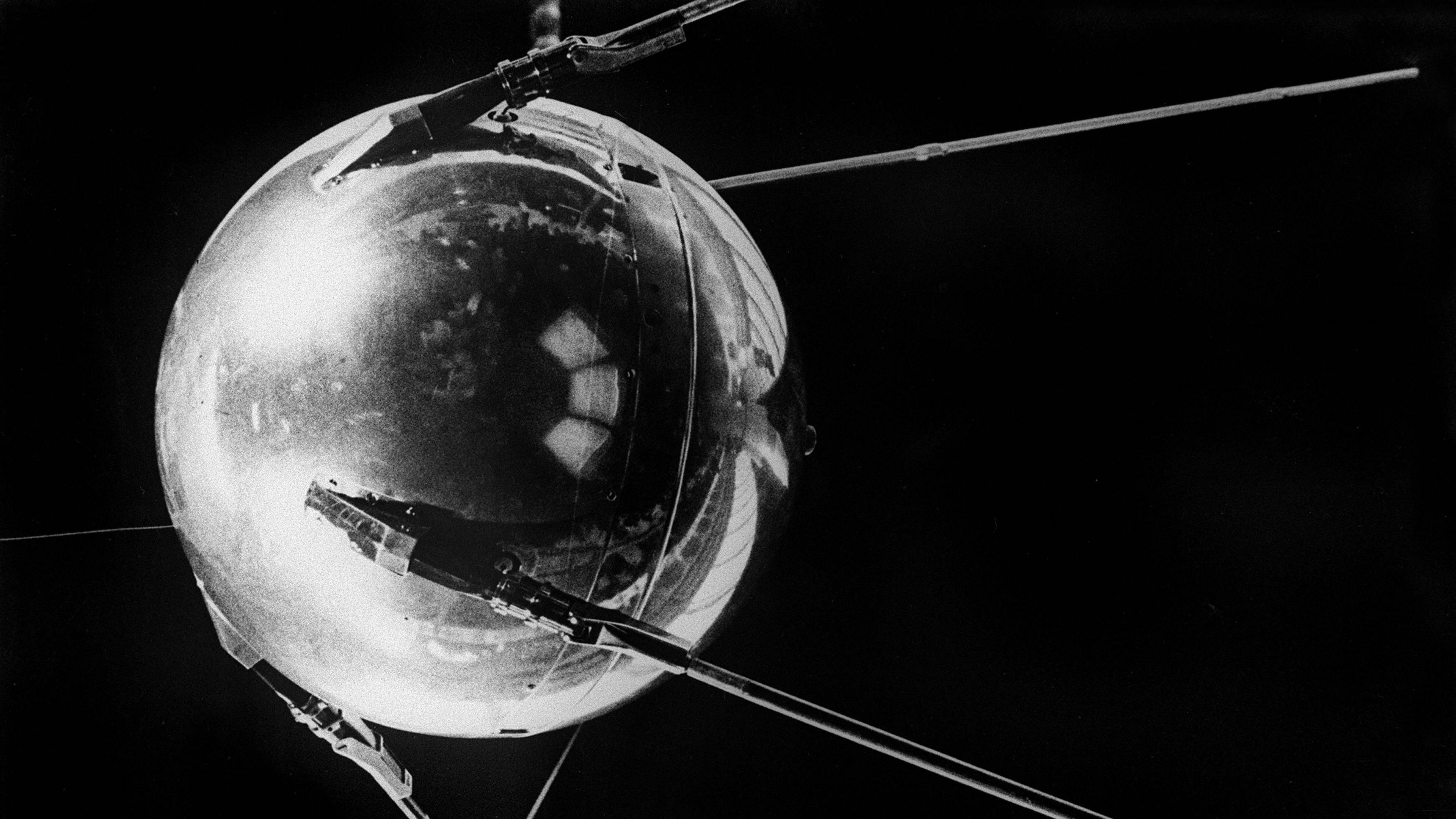

The Cold War-era intelligence gathering grew out of earlier pioneering work at Jodrell Bank when the radio telescope tracked Sputnik - the first unmanned satellite - when it was launched by the USSR in 1957.

Jodrell Bank's founding father Sir Bernard had been facing the sack at the time due to his radio telescope's escalating budget.

But when it swung into action to track Sputnik's launch, it became indispensable.

Sir Bernard recalled years later: "I was in the laboratory where the receiving apparatus was and suddenly, before midnight, I saw the most dramatic echo.

"A huge echo - the echo of the intercontinental missile travelling over the lake to a distributed speed of 17,000 miles an hour."

He added: "And we developed this photograph, and I projected it to a packed media, cameramen, the newspapermen, in the small lecture room.

"This wonderful echo, the only instrument in the Western world which could detect the launching of the Sputnik."

"And the press recognised immediately that this was the intercontinental missile."

It led to a hidden role for the University of Manchester's radio telescope.

British and US intelligence chiefs soon realised its potential for monitoring the Soviets' inter-continental ballistic missile tests.

These rockets were designed to carry nuclear warheads many times more powerful than the atomic bombs which devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War Two.

Sputnik was launched from the Soviet Union's Baikonur cosmodrome in what is now Kazakhstan. Its high-pitched signal was picked up in rural Cheshire.

Staff would soon notice GCHQ's "secret squirrels" from Cheltenham visiting two labs above the foyer of the control building.

Sir Bernard and his two members of staff were sworn to secrecy.

The Jodrell Bank monitoring also discovered failed Soviet attempts to land a robotic space probe on the moon to scoop up a sample of lunar soil and bring it back to Earth.

Jodrell Bank's team heard the telltale signals as the probe crashed into the surface of the moon.

Bizarrely, when the signal stopped the head of the Soviet Academy of Sciences rang Sir Bernard to ask him if he had been listening to the spacecraft's signals.

The Soviets asked for a copy of the recording and told him they already had a "man in the air" on the way to Manchester Airport.

In scenes that perhaps could have come straight out of a James Bond movie, an engineer carried a copy of one of the tapes in an envelope and drove up to the airport.

Once there, he handed the envelope to a Soviet official who flew straight back to Moscow.

The telescope was a vital part of the UK's defence as tensions grew between the USSR and Nato during the Cold War

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Greater Manchester

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. You can also send story ideas via Whatsapp to 0808 100 2230.

Related topics

- Published7 November

- Published20 July 2019