From India to Britain and back: The cartoonist who fought censors with a smile

Abu's cartoons sharply captured the media's servility during the Emergency

- Published

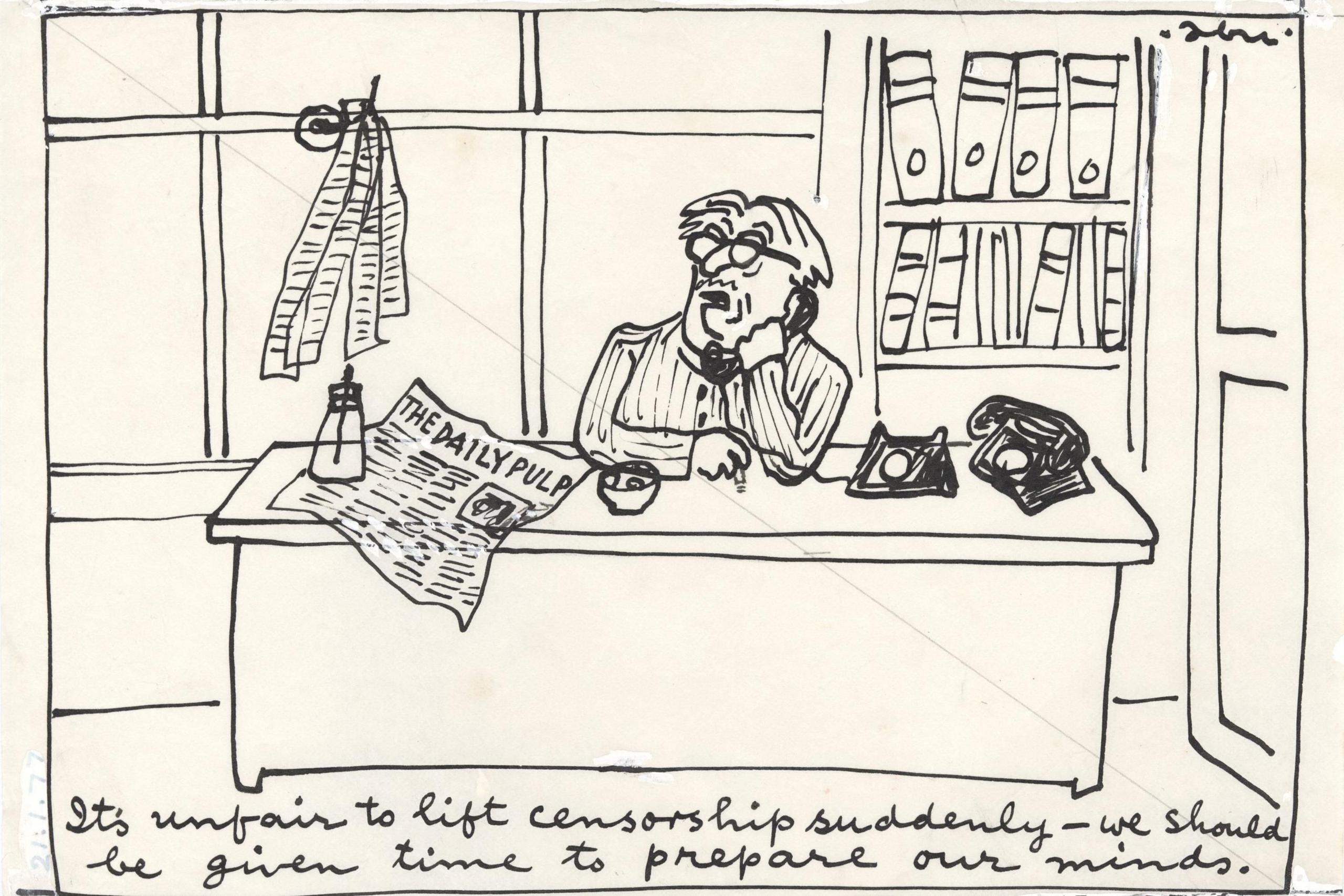

"It's unfair to lift censorship suddenly," growls a grizzled newspaper editor into the phone, a copy of The Daily Pulp sprawled across his desk. "We should be given time to prepare our minds."

The cartoon capturing this moment - piercing and satirical - is the work of Abu Abraham, one of India's finest political cartoonists. His pen skewered power with elegance and edge, especially during the 1975 Emergency, a 21-month stretch of suspended civil liberties and muzzled media under Indira Gandhi's rule.

The press was silenced overnight on 25 June. Delhi's newspaper presses lost power, and by morning censorship was law. The government demanded the press bend to its will - and, as opposition leader LK Advani later famously remarked, many "chose to crawl".

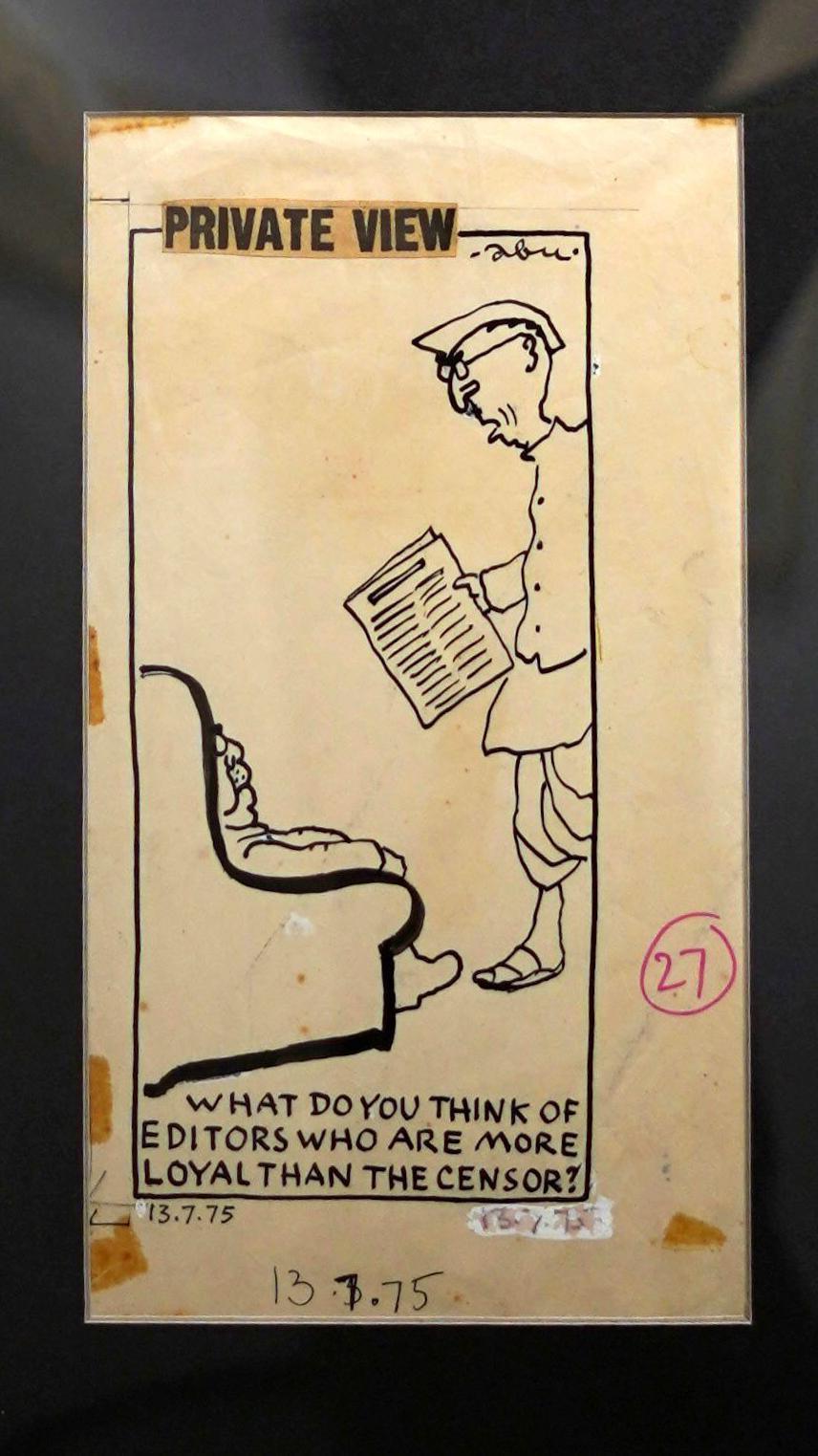

Another famous cartoon - he signed them Abu, after his pen name - from that time shows a man asking another: "What do you think of editors who are more loyal than the censor?"

In many ways, half a century later, Abu's cartoons still ring true.

India currently ranks 151st in the World Press Freedom Index, external, compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders. This reflects growing concerns about media independence under Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government. Critics allege increasing pressure and attacks on journalists, acquiescent media and a shrinking space for dissenting voices. The government dismisses these claims, insisting that the media remain free and vibrant.

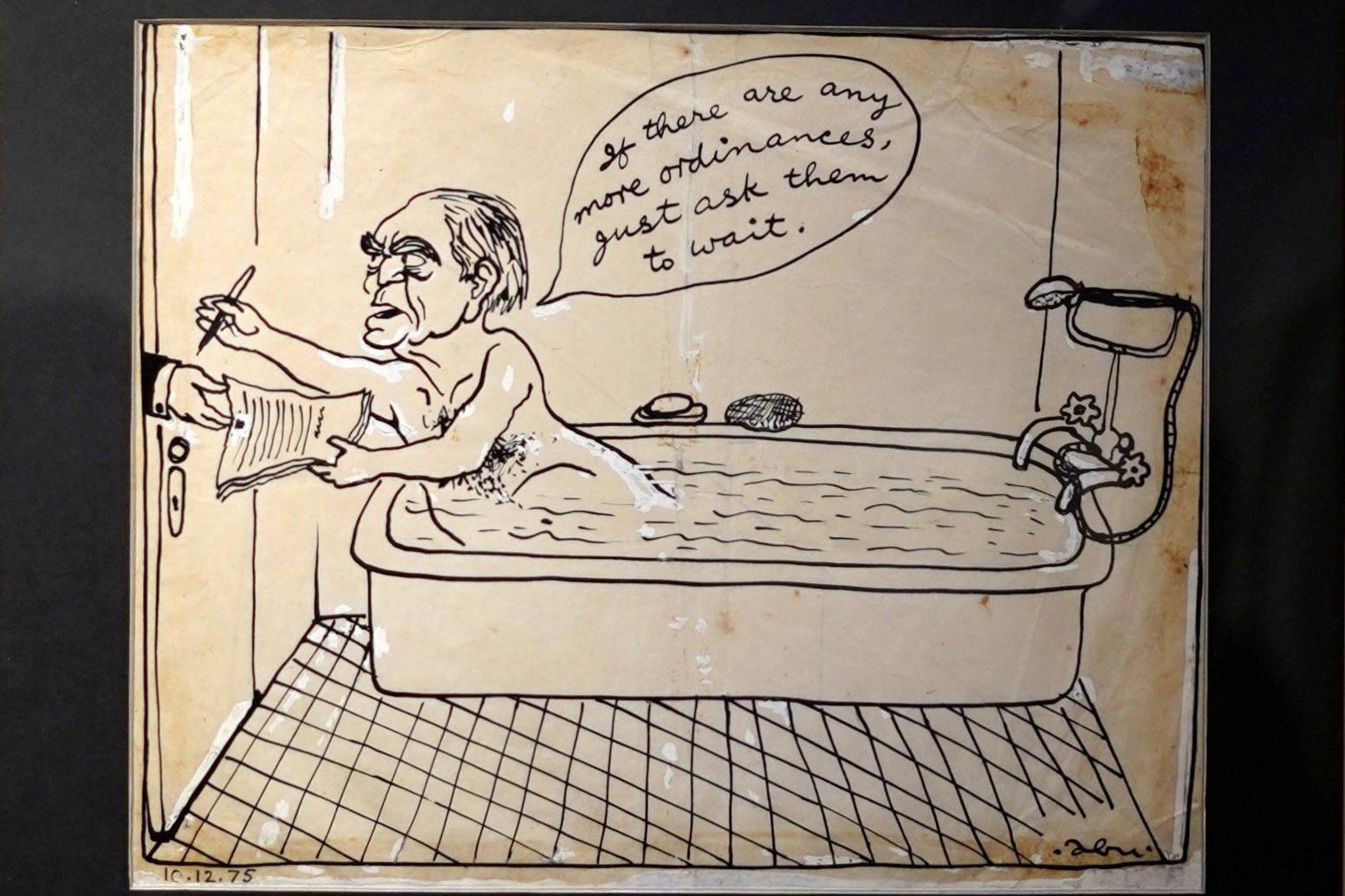

One of Abu's iconic Emergency cartoons shows President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the proclamation from his bathtub

After nearly 15 years drawing cartoons in London for The Observer and The Guardian, Abu had returned to India in the late 1960s. He joined the Indian Express newspaper as a political cartoonist at a time when the country was grappling with intense political upheaval.

He later wrote that pre-censorship - which required newspapers and magazines to submit their news reports, editorials and even ads to government censors before publication - began two days after the Emergency was declared, was lifted after a few weeks, then reimposed a year later for a shorter period.

"For the rest of the time I had no official interference. I have not bothered to investigate why I was allowed to carry on freely. And I am not interested in finding out."

Many of Abu's Emergency-era cartoons are iconic. One shows then President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the proclamation from his bathtub, capturing the haste and casualness with which it was issued (Ahmed signed the Emergency declaration that Gandhi had issued shortly before midnight on 25 June).

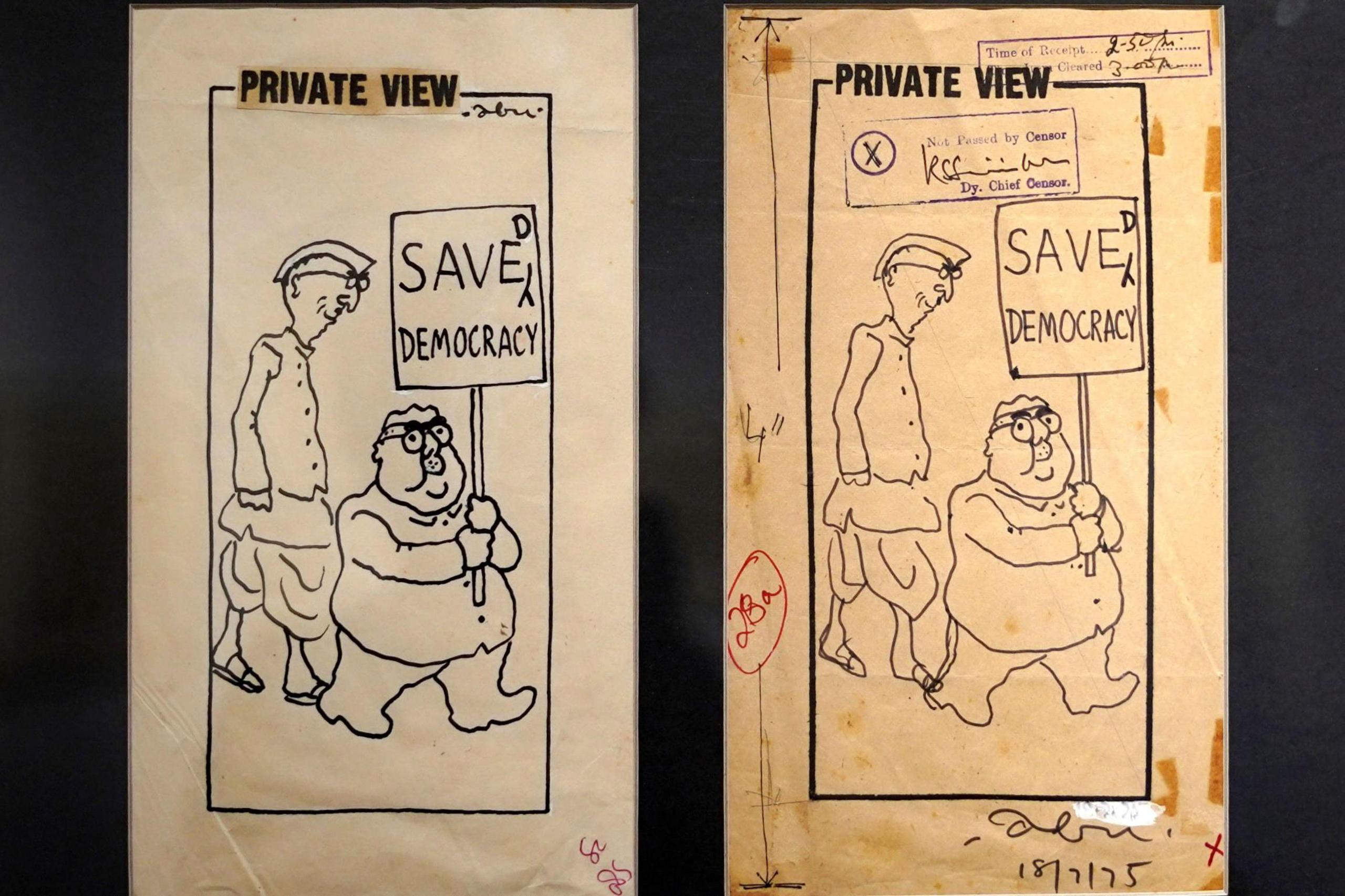

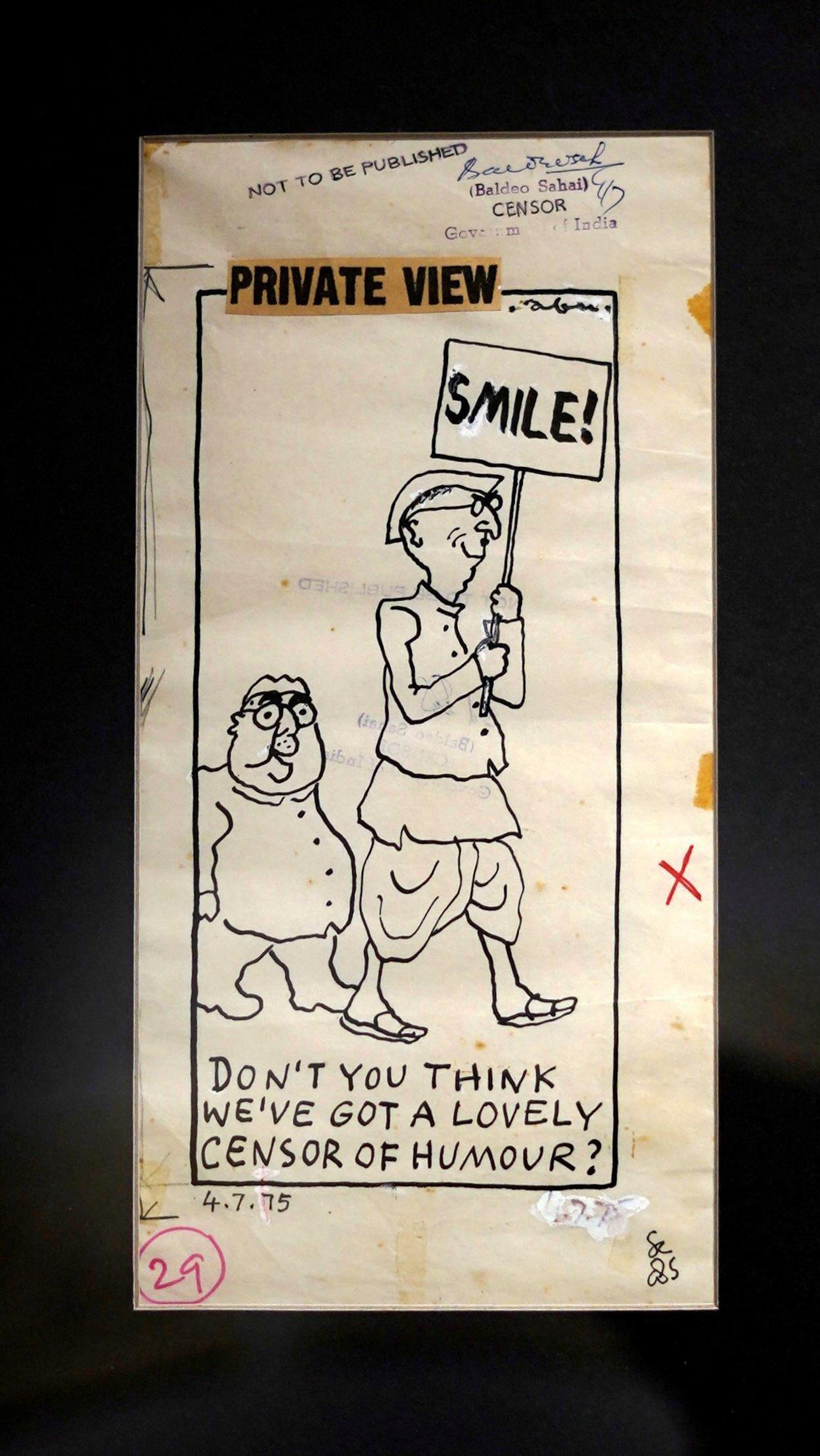

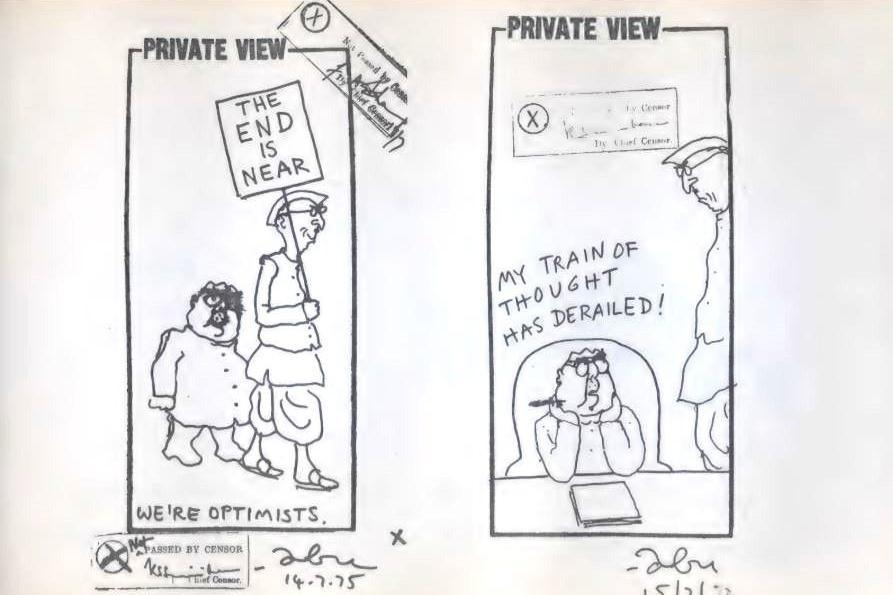

Among Abu's striking works are several cartoons boldly stamped with "Not passed by censors", a stark mark of official suppression.

In one, a man holds a placard that reads "Smile!" - a sly jab at the government's forced-positivity campaigns during the Emergency. His companion deadpans, "Don't you think we have a lovely censor of humour?" - a line that cuts to the heart of state-enforced cheer.

Another seemingly innocuous cartoon shows a man at his desk sighing, "My train of thought has derailed." Another features a protester carrying a sign that reads "SaveD democracy" - the "D" awkwardly added on top, as if democracy itself were an afterthought.

Among Abu's striking works are several censored cartoons, stamped with the censor's ink

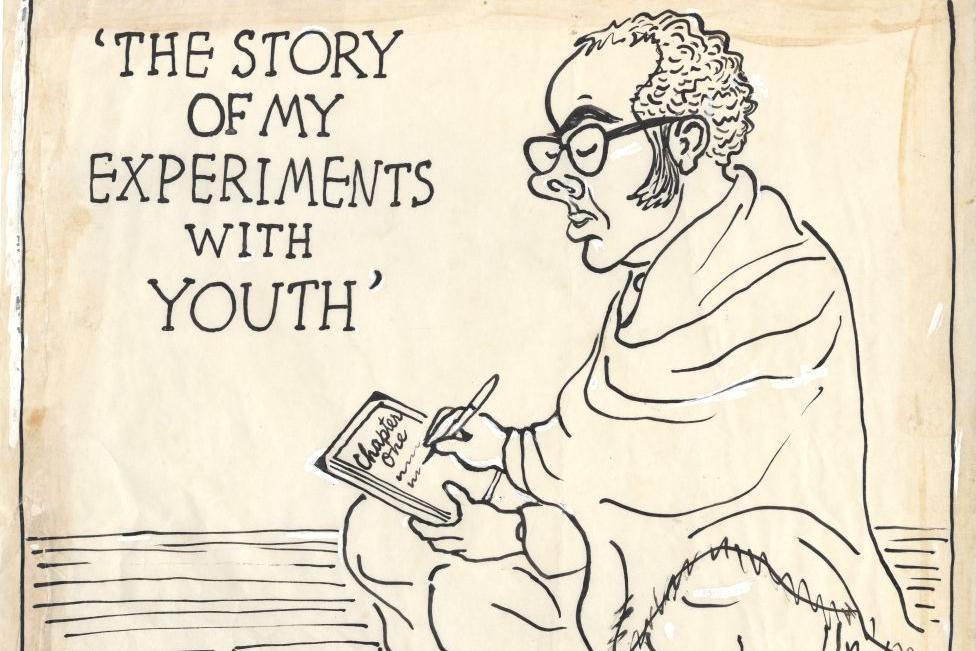

Abu also took aim at Sanjay Gandhi, the unelected son of Indira Gandhi, who many believed ran a shadow government during the Emergency, wielding unchecked power behind the scenes. Sanjay's influence was both controversial and feared. He died in a plane crash in 1980 - four years before his mother, Indira, was assassinated by her bodyguards.

Abu's work was intensely political. "I have come to the conclusion that there's nothing non-political in the world. Politics is simply anything that is controversial and everything in the world is controversial," he wrote in Seminar magazine in 1976.

He also bemoaned the state of humour - strained and manufactured - when the press was gagged.

"If cheap humour could be manufactured in a factory, the public would rush to queue up in our ration shops all day. As our newspapers become progressively duller, the reader, drowning in boredom, clutches at every joke. AIR [India's state-run radio station] news bulletins nowadays sound like a company chairman's annual address. Profits are carefully and elaborately enumerated, losses are either omitted or played down. Shareholders are reassured," Abu wrote.

In a tongue-in-cheek column for the Sunday Standard in 1977, Abu poked fun at the culture of political flattery with a fictional account of a meeting of the "All India Sycophantic Society".

The spoof featured the society's imaginary president declaring: "True sycophancy is non-political."

The satirical monologue continued with mock proclamations: "Sycophancy has a long and historic tradition in our country… 'Servility before self' is our motto."

Abu also took aim at Sanjay Gandhi, the controversial unelected son of Indira Gandhi

Abu's parody culminated in the society's guiding vision: "Touching all available feet and promoting a broad-based programme of flattery."

Born as Attupurathu Mathew Abraham in the southern state of Kerala in 1924, Abu began his career as a reporter at the nationalist Bombay Chronicle, driven less by ideology than a fascination with the power of the printed word.

His reporting years coincided with India's dramatic journey to independence, witnessing firsthand the euphoria that gripped Bombay (now Mumbai). Reflecting on the press, he later noted, "The press has pretensions of being a crusader but is more often a preserver of the status quo."

After two years with Shankar's Weekly, a well-known satire magazine, Abu set his sights on Europe. A chance encounter with British cartoonist Fred Joss in 1953 propelled him to London, where he quickly made a mark.

His debut cartoon was accepted by Punch within a week of arrival, earning praise from editor Malcolm Muggeridge as "charming".

Freelancing for two years in London's competitive scene, Abu's political cartoons began appearing in Tribune and soon attracted the attention of The Observer's editor David Astor.

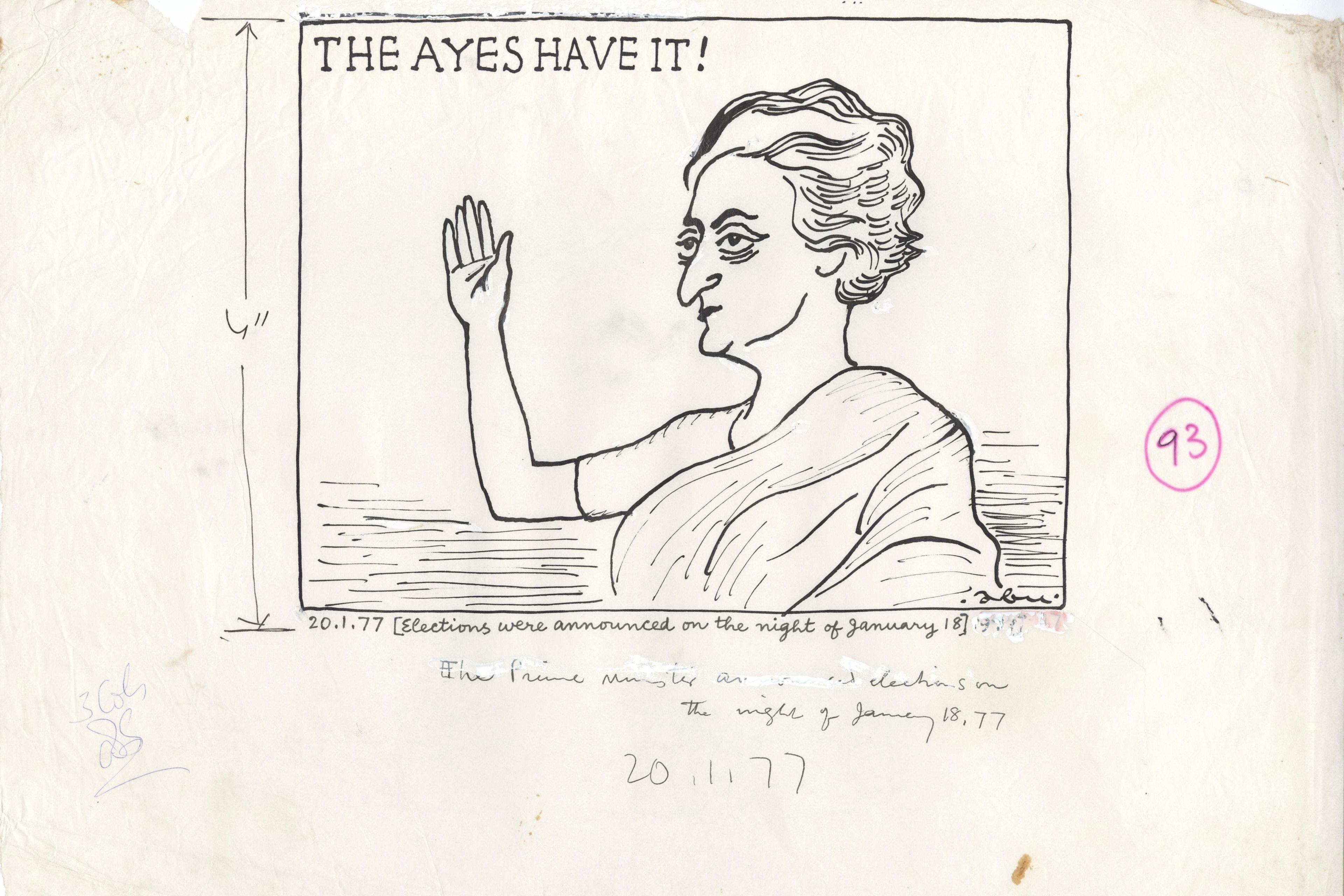

Abu's cartoon marks Gandhi calling the 1977 election, ending the Emergency. She lost the election

Abu spent a decade at The Observer and three years at The Guardian

Astor offered him a staff position with the paper.

"You are not cruel like other cartoonists, and your work is the kind I was looking for," he told Abu.

In 1956, at Astor's suggestion, Abraham adopted the pen name "Abu", writing later: "He explained that any Abraham in Europe would be taken as a Jew and my cartoons would take on slant for no reason, and I wasn't even Jewish."

Astor also assured him of creative freedom: "You will never be asked to draw a political cartoon expressing ideas which you do not yourself personally sympathise."

Abu worked at The Observer for 10 years, followed by three years at The Guardian, before returning to India in the late 1960s. He later wrote he was "bored" of British politics.

Beyond cartooning, Abu served as a nominated member of India's upper house of Parliament from 1972 to 1978. In 1981, he launched Salt and Pepper, a comic strip that ran for nearly two decades, blending gentle satire with everyday observations. He returned to Kerala in 1988 and continued to draw and write until his death in 2002.

But Abu's legacy was never just about the punchline - it was about the deeper truths his humour revealed.

As he once remarked, "If anyone has noticed a decline in laughter, the reason may not be the fear of laughing at authority but the feeling that reality and fancy, tragedy and comedy have all, somehow got mixed up."

That blurring of absurdity and truth often gave his work its edge.

"The prize for the joke of the year," he wrote during the Emergency, "should go to the Indian news agency reporter in London who approvingly quoted a British newspaper comment on India under the Emergency, that 'trains are running on time' - not realising this used to be the standard English joke about Mussolini's Italy. When we have such innocents abroad, we don't really need humorists."

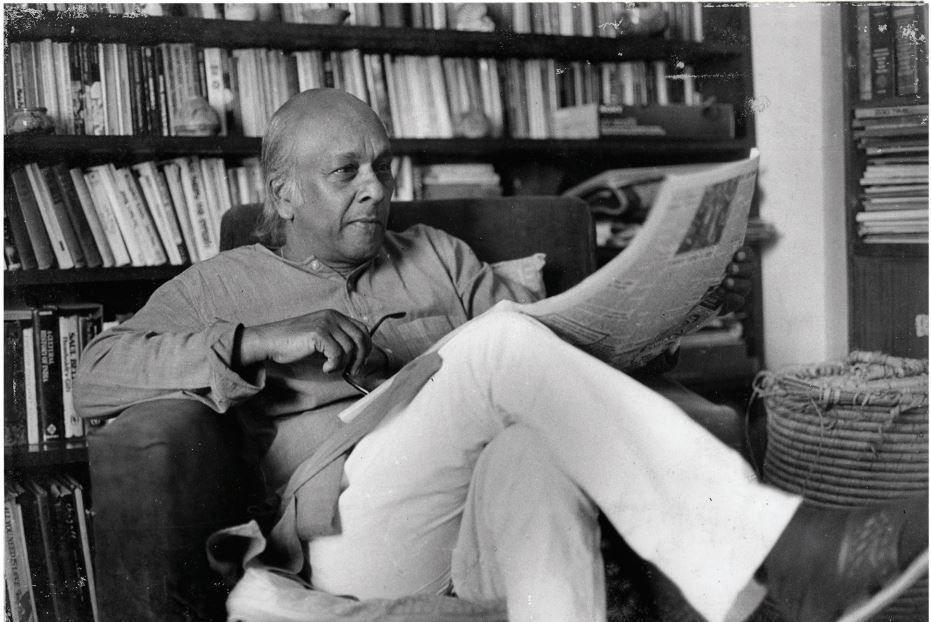

Abu's cartoons and photograph, courtesy Ayisha and Janaki Abraham