Will railways really be expanded across the island?

The All-Island Strategic Rail Review was published last month

- Published

As the saying goes, wait hours for a bus and two come at once.

Wait years for an All-Island Strategic Rail Review, and you get 32 recommendations including new or restored railway lines on both sides of the border, external.

Among the recommendations is a 50-year old plan to create a railway link at Belfast International Airport.

So why has it taken so long - and how likely is it that any of the review's grand ambitions will ever become a reality?

What are these recommendations from an NI perspective?

A railway link at Belfast International Airport has been talked about for 50 years

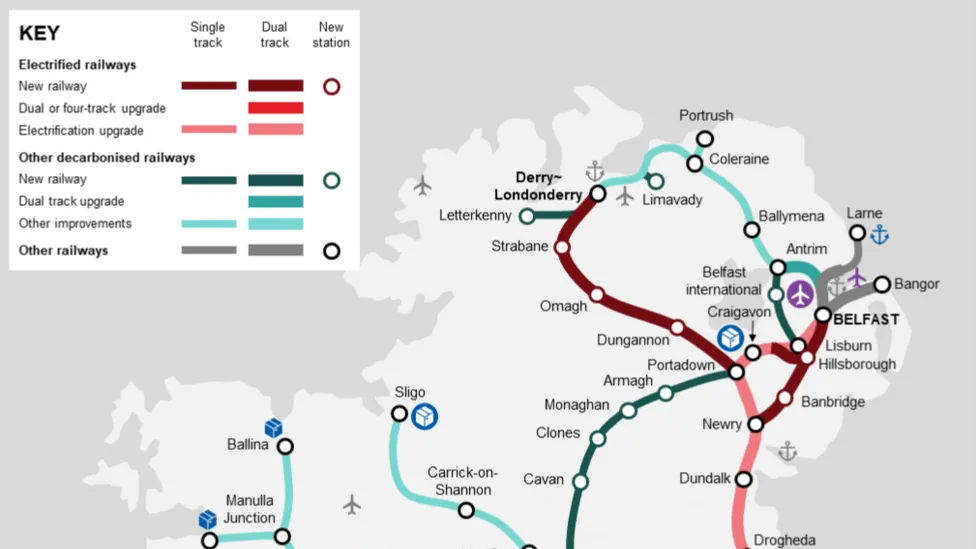

As well as a station at the airport, created by reopening the Antrim-Lisburn line, there would be more intercity services, reinstatement of lines including from Londonderry to Portadown and Portadown to Armagh, a new station at Craigavon and cross-border connections from Londonderry to Letterkenny and from Armagh to Monaghan.

There are also plans to build a higher-speed railway from Belfast to Newry, with new stations at Dromore and Banbridge.

Some elements of the review are already being acted on, with the construction of the new Grand Central Station in Belfast and plans to increase the frequency of services between Belfast and Dublin.

Come 2050, the journey from north-west to south-east and beyond should look very different to how it is now and making that trip by rail would be a serious option.

But none of this would come cheap.

The all-island costs are estimated between €35bn (£29bn) and €37bn (£31bn) in 2023 terms, with Northern Ireland committed to paying 25%.

The review says that works out at roughly £310m a year over the 25-year span of the review.

Is there money available?

Dr Eoin Magennis said what Northern Ireland spends on public transport overall is still less than the £300m estimated for rail

As we all know, the "money tree" has not been liberally fruiting in recent years and every department has been asked to make savings.

The £310m a year that the review requires of Northern Ireland is for rail alone.

Principal economist at Ulster University's Economic Policy Centre, Dr Eoin Magennis, said it was significantly more than is normally spent, not just on rail.

"In any given year, our budget for bus, rail and ports as well is about £250m, spent on the three of those together," he said.

"So to raise that up to £300m for rail alone is certainly ambitious.

"Other priorities would come under pressure or would have to be looked at.

"Some of that could be in loans from the European Investment Bank, but nonetheless you're talking significant investment."

That means tough choices.

Infrastructure Minister John O'Dowd said there was a need to change transport use

Stormont Infrastructure Minister John O'Dowd told BBC News NI the funds are available.

He said it was about “decisions I will make and future ministers and the executive will make about how this plan is implemented".

“I don’t think we have any choice," he said.

“Climate change is a reality and we have to change how we transport people and goods.

“Rail is a great way of doing that.”

Dr Magennis is cautious, given the need for a ringfenced capital budget.

He said it was difficult to see network operator Northern Ireland Railways being able to come up with the money without fare increases or a change in how it operated.

He also said it was important to consider other forms of public transport, including buses.

Why the focus on trains?

The Enterprise service links Belfast and Dublin

The big driver is climate change and targets for reducing emissions that are now legally obliged to be met.

Transport is the second-biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in Northern Ireland.

And it was one of only two sectors to show increases in emissions compared to the base year of 1990.

Decarbonising the rail network by moving mostly to electric trains, with the remainder running on a hybrid of electricity and hydrogen, is an easy win to cut emissions.

Making rail more accessible and more widely available should also, in theory, encourage more people to leave the car at home.

Ulster University historian Emmet O'Connor said when railway lines were reduced in favour of cars, planners were not "thinking ahead"

It is a big shift from thinking in the 20th century, said Ulster University historian Emmet O'Connor.

In the 1920s there were 32 mostly loss-making railways and these were gradually cut back to just two, partly due to the impact of the partition of the island into Northern Ireland and the modern-day Republic of Ireland.

"The argument was that they weren't making any money, they weren't likely to make any money in the foreseeable future, people were switching to road transport and making use of the car," he said.

"They simply weren't thinking ahead."

But he said the tide had turned.

"I think there's a recognition that the railway is the way of the future for environmental reasons, but also for social and economic reasons," he said.

What about Fermanagh?

The aim of the review is to create a future-proofed 21st-century transport system that works for the whole island and gives people the freedom to move around without doing harm to the environment while also creating choice, convenience, accessibility and practicality.

One place that would not be connected is Fermanagh.

By 2050 when the recommendations of the review are implemented, it would be the only county in the UK and Ireland with no train line.

That makes this an "interim" review for engineer Karen McShane.

"What you're doing is looking to 2050 to achieve the climate change targets, so you're implementing what you know will be used and where the prime and heaviest movements are," she said.

Engineer Karen McShane said while Enniskillen may have been left out, the plan for Omagh is a positive for connection to the west

A section in the report is devoted to Enniskillen, saying it would not be financially viable or self-sustaining.

The 40km-connection required to Omagh would cost £400m, according to the infrastructure minister.

"They're looking at it at this stage saying there is not enough justification today to justify this level of investment to bring the rail through to Fermanagh," Ms McShane said.

"But with that new western connection, you do have the Omagh connection, so you could drive to Omagh and get on there.

"So you need to supplement this with park-and-rides and public transport linkages that will take you from Enniskillen to the station so if you wanted to you could still get on to the network.

"But we know this is a stepping-stone, this is the next 25-year plan moving forward."

One thing that has inched closer to being a reality is the airport connection.

When the review was published on 31 July, politician Lord Kilclooney tweeted that he remembered viewing plans to create a rail link at Belfast International Airport when he was a minister in Brian Faulkner's Stormont government in the early 1970s.

There would be new lines as well as upgrades to existing links

Will it all happen?

For Northern Ireland, in contrast to the Republic, it is not so much about new lines as restoring connections removed half a century ago or more.

That makes the recommendations more likely.

But 2050 transport may be more 50/50 when viewed through a financial lens.

That monetary fly in the ointment is a big one, and only likely to get bigger.

Then again, missing the 2050 net zero target and not reducing emissions is also big, with potentially wider, worse and longer-term consequences.

There is also the issue of an electricity grid infrastructure that needs investment to carry the amount of renewable energy required for wide-scale decarbonisation in transport and beyond.

So it remains to be seen where the political will lies and just how committed politicians and planners really are to this vision.