'A bail house wasn't a safe place for a female'

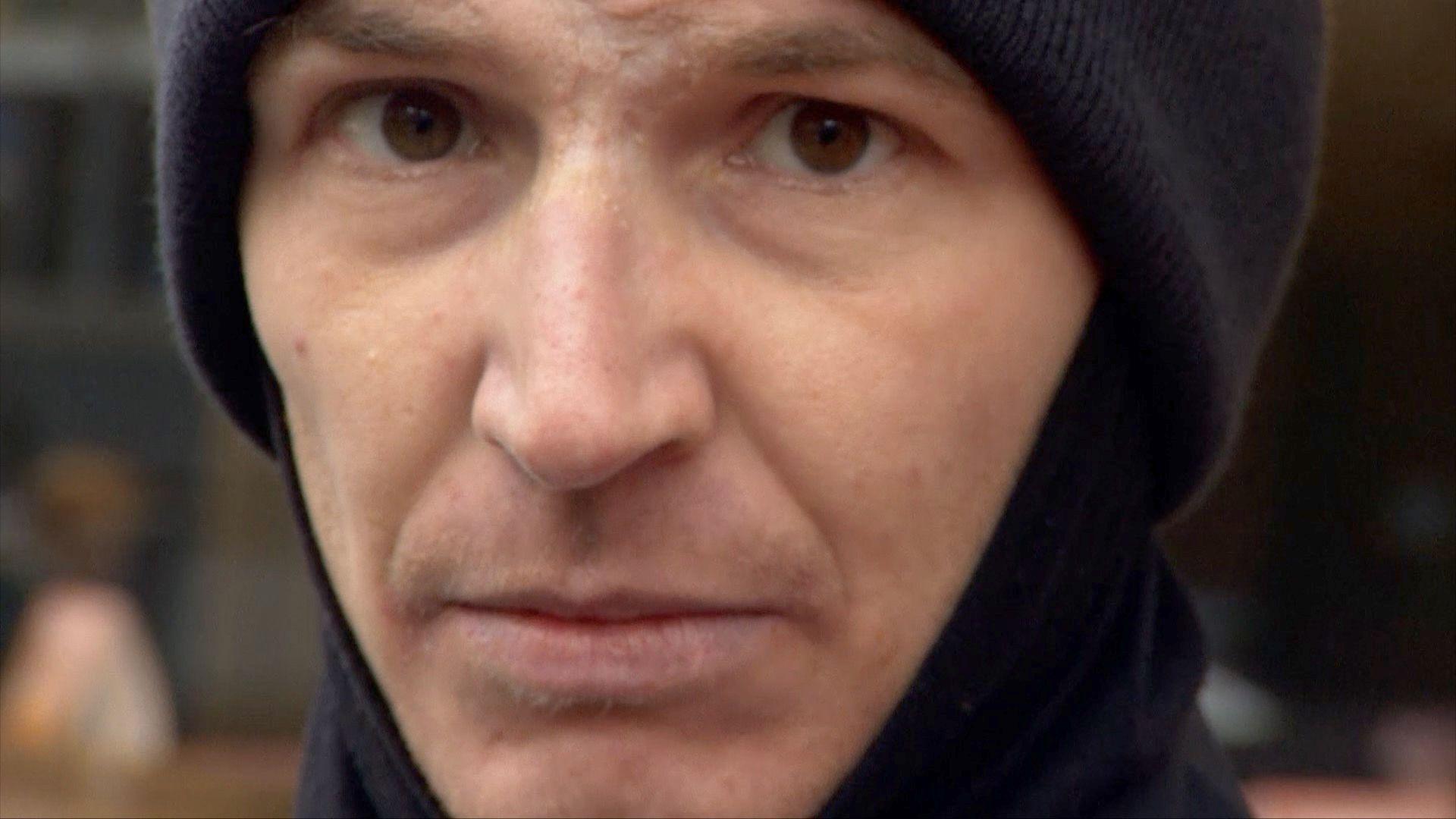

Dainya Ebanks left HMP Holloway on licence in July 2008

- Published

"It really wasn't a safe place for a female," says Dainya Ebanks, reflecting on her experience of a bail house after leaving prison.

Recent data from the Ministry of Justice, external has found that more than half of women who left prison were released without stable accommodation and more than one in 10 slept rough when they returned to the community.

Ms Ebanks, who left HMP Holloway on licence in July 2008 aged 20 having served time in jail for drug offences, said she was not surprised by the findings.

"I have not felt settled since," she told BBC London.

'I almost felt alone'

When Ms Ebanks left HMP Holloway, she was due to stay at her family home in Acton and wear an electronic tag as part of her licence conditions.

But she said she felt overwhelmed and anxious about returning to the family dynamic.

“I didn’t even last the three to four months. I did not settle into that environment from being in prison,” she said.

"It was so surreal and all in one space and time. A lot of clashes were happening in the family home."

She said she "took it upon myself to contact my probation officer and let him know my situation" but found "he was not helpful".

"I almost felt alone, without any support."

Ms Ebanks said she threatened to breach her licence conditions, and only then received help finding other accommodation.

As a result she was given a ground floor room in a bail hostel close to her family in Acton, but that led to its own problems.

HMP Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders and it shut down in 2016

"I’m a female and I lived on the ground floor in a building full of men," she said.

"There was one other girl and the rest of them were men.

"There was no security, it wasn’t really a safe place for a female."

Ms Ebanks said she expected to benefit from support at the hostel, but that did not happen.

"With this bail hostel, there were stepping stones that would enable you to get your flat at the end, but they weren’t following those, so I wasn’t either. All of that support was gone.

"They put me back into a similar situation where the people around me and my peers are not good," she said.

The 36-year-old said that the situation meant "you just start not to care, you don’t look for a job, you start mixing with the wrong crowd".

"I used to think, I’m only 20, I’ve only just stepped out of my teenage years. I don’t feel like there was enough support for me," she said.

'Safer in prison'

Ms Ebanks moved into private accommodation with a friend in 2009, and has been renting ever since.

However, she said she could see "why some women will reoffend because they have that stability within the prison system.

"Sleeping rough isn’t safe. That alone can make somebody end up right back where they started."

The London Assembly's , externalhousing committee, external met on Tuesday to discuss the issues some women faced when they are released from prison.

John Plummer, coordinator at London Prisons Mission, told the meeting that in the capital, 50 women per month were released into homelessness.

"That is exactly the same number as when we started [in 2017-18]," he said.

"I am deeply ashamed of the fact we have made no improvement in that. That is two or three per borough per month."

The London Assembly's meeting also heard that women's housing needs when leaving prison were often met with additional issues including domestic abuse, poor mental and physical health, debts, parental issues and immigration.

"Sometimes going into temporary accommodation is not suitable," said Rachel Ozanne, director of programmes and partnerships at national charity Women in Prison.

"It needs to be a supported accommodation, but across the boroughs it really varies as to what those options are."

Mr Plummer added the issue was “by no means a London problem alone”.

Sam Julius, from Clinks, which represents the criminal justice voluntary sector, said that many women felt safer and more secure in prison.

"You are away from potential perpetrators of domestic abuse, you have a roof over your head," he said.

"That’s why one of the biggest issues within the current prison overcrowding crisis is the incredibly high level of recalls.

"You see the same people going in and out of prison."

The Ministry of Justice has previously said the government was "working with partners, including local councils and charities, to avoid anyone being released on to the street".

London rough sleeping figures hit record high

- Published27 June 2024

Cost of housing homeless people in London £4m a day

- Published25 October 2024

Ms Ebanks said when she threatened to breach her licence conditions, she was thinking about the routine and structure prison provided.

"I felt safe," she said. "I didn’t feel like my life was at risk. I didn’t feel like there was no support, because there was always an officer that you could speak to or another inmate."

She said that once released, there was "no sense of security".

"I almost felt like a prisoner within society. I didn’t have help.

"I’m a grown woman now with two children. I’ve changed my whole life around and still you get looked down upon because you have a criminal record.

"I have not felt settled since coming out of prison."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published11 November 2024

- Published1 November 2024

- Published10 November 2024