Should we drop ethnic minority for global majority?

The term "people of the global majority" was brought to prominence by Rosemary Campbell Stephens

- Published

Over the past few years numerous organisations as well as the UK government have dropped the acronym BAME, which stands for black, Asian and minority ethnic.

While other terms such as ethnic minority and people of colour are still routinely used, another appears to be building momentum - people of the global majority.

Global majority refers to people who are "black, Asian, brown, dual-heritage, indigenous to the global south, and or have been racialised as 'ethnic minorities'" and "represent approximately 80% of the world's population", according to educator and activist Rosemary Campbell-Stephens, who coined the term.

With Black History Month in the UK well under way we look at the origins of the term and reflect the debates around its use when talking about ethnicity.

October is Black History Month in the UK

Campaigner Donna Ali said she liked the term but it had pros and cons.

"It speaks to unity, it gives you prominence and I think it helps us feel not less than," said Donna, founder of BE.Xcellence, a community interest company that aims to raise the representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic people in powerful positions in Wales.

"[The word] 'minority' can make you feel that you are less than, you are the least, when in reality we are the more in terms of numbers," she said.

She said the case against was it "puts everyone in one lump".

"What it says to me is 'them and us' and I hate that, it shouldn't be about everyone black and brown on that side and whites on that side, it's absolutely ridiculous."

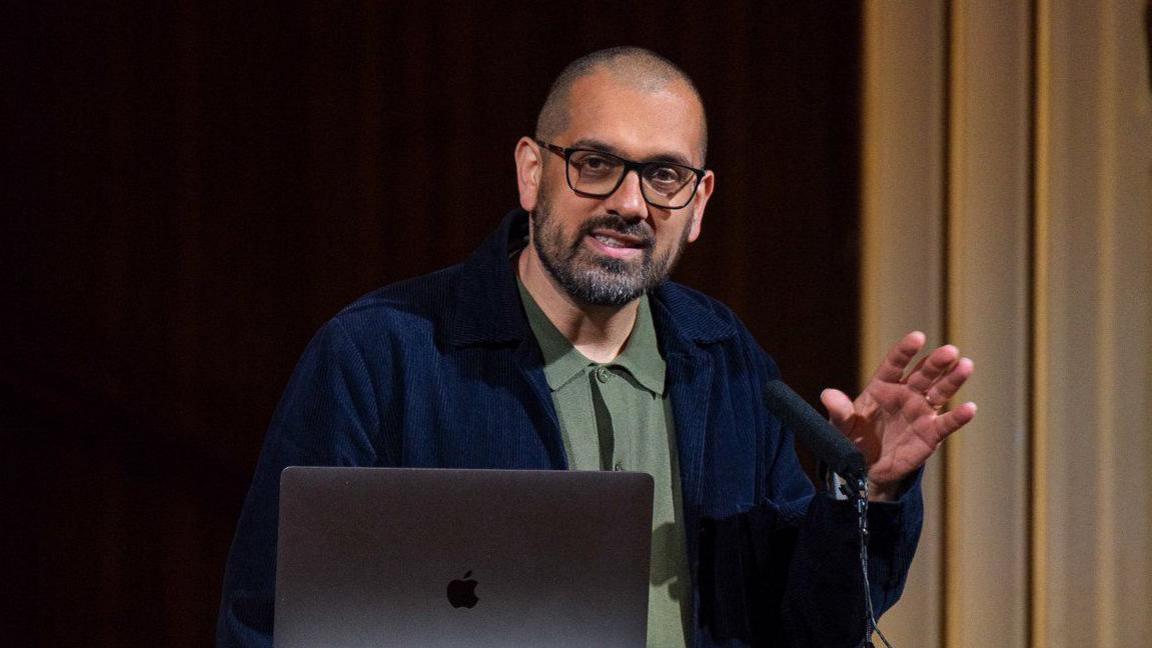

Darren Chetty has published academic work on philosophy, education, racism, dialogue, children's literature and hip-hop culture

Author and academic Darren Chetty also thought the term had benefits and drawbacks.

He said he liked that it "reframes the idea that people of colour or people who aren't white constitute the majority of people in the world".

"That can have, I guess, a psychological boost to people, it can also highlight when there's an absence of people of colour just how jarring that is given the global demographics," said Darren, who grew up in Swansea.

He said a problem was it "doesn't make reference to racialisation in any way" and like BAME "treats people as a sort of homogenous group".

He said grouping everyone together also ran the risk of "being in the room privilege".

"You assume that by asking one person who is a person of colour to speak that you have the view of the global majority and there are clearly important distinctions within that group," he said.

The term BAME began falling out of use following very similar criticism - that it grouped all ethnic minorities together.

In March 2022, the UK government commitment to no longer using BAME following a review on the causes for race inequality in the UK by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities.

It said it would use specific ethnic classifications, external wherever possible, but where it was absolutely necessary to group together people from different ethnic minority backgrounds it would use "ethnic minorities" or "people from ethnic minority backgrounds".

The term global majority refers to about 80% of the world's population

The term "people of the global majority" was brought to prominence by Rosemary Campbell Stephens, an educator and anti-racist activist of Black African Caribbean heritage.

It came about through her work to diversify leadership at London schools.

When the National Council of Voluntary Organisations adopted the term last year, it said it was using the term in place of BAME, Bipoc (black, Indigenous, and people of colour) and ethnic minorities.

"We've heard from many people who now consider these terms outdated and problematic. This includes the UK government, who have stopped using the term BAME," it said.

When National Museums Liverpool made the change it said it was "more reflective and more empowering".

What does it mean to be Welsh?

- Published6 March 2022

Head teacher who faced racism fights for change

- Published6 November 2022

UK broadcasters agree to avoid BAME acronym

- Published7 December 2021

Darren said where the term originated mattered.

"One of the resistance to BAME was it never came from activists and communities, it came from the government," he said.

He said it was inevitable that people who throughout history had been described by others would "as an act of empowerment decide that they would describe themselves on their own terms".

Donna thinks the term has the potential to ruffle feathers.

"There will be people out there, white people if you like, who will be agitated by that term, because it is taking away that Eurocentric power, the white supremacy," she said.

The term has had push-back from some commentators.

When interviewing political commentator Connor Tomlinson on Talk TV, journalist Julia Hatley Brewer said: "Global majority means non-white so lumping everyone in together... its not just anti-white, it's just a bit racist, external, isn't it?"

National Trust used the term when launching a walking project and received a public backlash, with some X users accusing it of "virtue signalling" and "excluding white people".

In a piece for the Independent, think tank director Sunder Katwala argued the term was a step backwards, external for ethnic minorities and erased their unique cultural heritage in the name of inclusiveness.

Writing in political magazine Spiked, writer Rakib Ehsan argued it was a "fundamentally useless term", external that "makes so little sense in the context of the UK".

Donna hosts a weekly radio show to amplify black-owned minority businesses in south Wales

Something both Darren and Donna agree on is that the concept of race itself is highly problematic.

"Racialisation is an ongoing process but it's not an essential quality, there aren't such things as races but because historically it has been taken that there were such things as races it has even affected law and policy and race as a division has had a social reality," said Darren.

"I wish we could get rid of the word race and just start seeing each other as human beings," said Donna.

She would like to see further language change, for instance using infusion instead on inclusion.

"Inclusion says to me 'this is our place, we're including you as minorities' but if you're inviting somebody you can also uninvite them," she said.

For Darren, the most important thing to consider when choosing what language to use is context.

"So the time and the place where you're using the term and the purpose - what are you using it for? Why is it being discussed?," he said.

"Using the right terms can be important, we don't want to insult and offend people but those terms in my view are only a means to an end," said Darren.

"The work to understand what language might be useful is certainly not as hard as the work that’s involved in addressing racism."