Brewing legacy: The coffee factory that shaped a town

The General Foods factory has dominated Banbury's skyline since the mid-1960s

- Published

When news broke last month that Banbury's coffee factory would be closing down after six decades, many in the town mourned it like a death in the family.

Dutch coffee-making giants Jacobs Douwe Egberts (JDE) revealed its plans to close the plant, which currently employs about 160 people, saying it had "not been an easy decision".

The factory stood as one of the Oxfordshire town's largest employers, with generations of workers passing through its gates under its various name changes.

Most locals still refer to the site as General Foods (GF), after the US company that first opened the factory in the mid-1960s.

As one former employee, who happens to also be my dad, put it to me: "GF was Banbury."

Another added that the plant had been "part of the town's DNA".

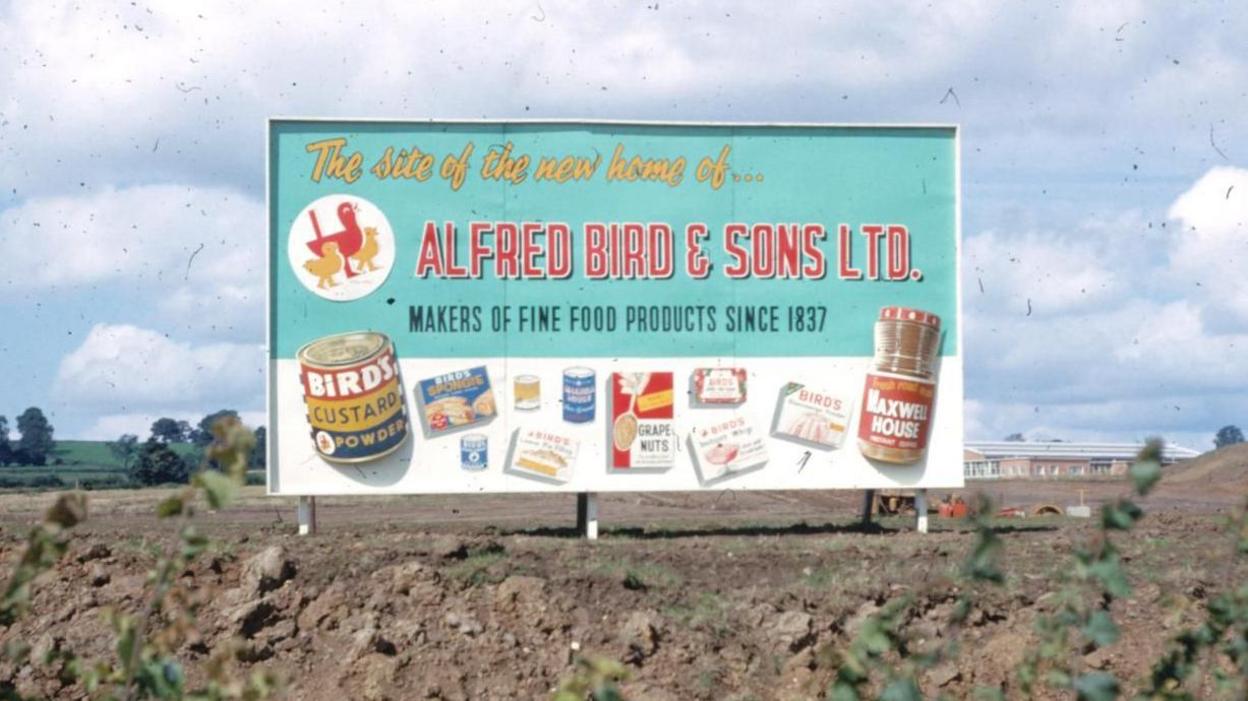

Alfred Bird's announced the move to the north of Banbury in 1963

As well as coffee, the site also produced iconic desserts over the years - including Bird's Custard, Dream Topping and Angel Delight.

It first opened as an Alfred Bird's factory in 1964, after GF decided the company's production base should be relocated from its previous home in Birmingham.

Thousands from the Midlands and London took the chance for new employment, and moved themselves and their families to the sleepy north Oxfordshire market town.

Among those to relocate were Rosemary and Brian Barratt, who moved from London in 1963.

As part of the London Overspill project to relocate the capital's population to towns across the south of England, the couple heard about Bird's scheme in Banbury.

"I had one interview with a General Foods bloke, and then we had a further interview, quite a few weeks later where they all picked us up in Camberwell and brought us down to Banbury on a coach," Mr Barratt explained.

"It consisted of a medical that involved a doctor listening to my chest and then asking if I could hear his watch.

"Nothing happened for a few weeks and, all of a sudden, we got a letter saying that I'd got the job."

The couple were given a house in the town by GF, but said the move was "very hard", adding: "We'd never even heard of Banbury!"

Rosemary and Brian Barratt said their move from London had been "very hard"

Alongside the Barratts were my own grandparents, Jean and John Gudge - who brought their three children, including my dad Michael, along with them.

My dad explained that my grandad had been working as a London bus driver when "this better prospect came up".

"They were told that they could relocate and there was a chance that he'd get a house and a good job," he said.

"There were loads that came, including the clippie (conductor) who worked on the bus with dad and ended up moving in the same street as us to start with."

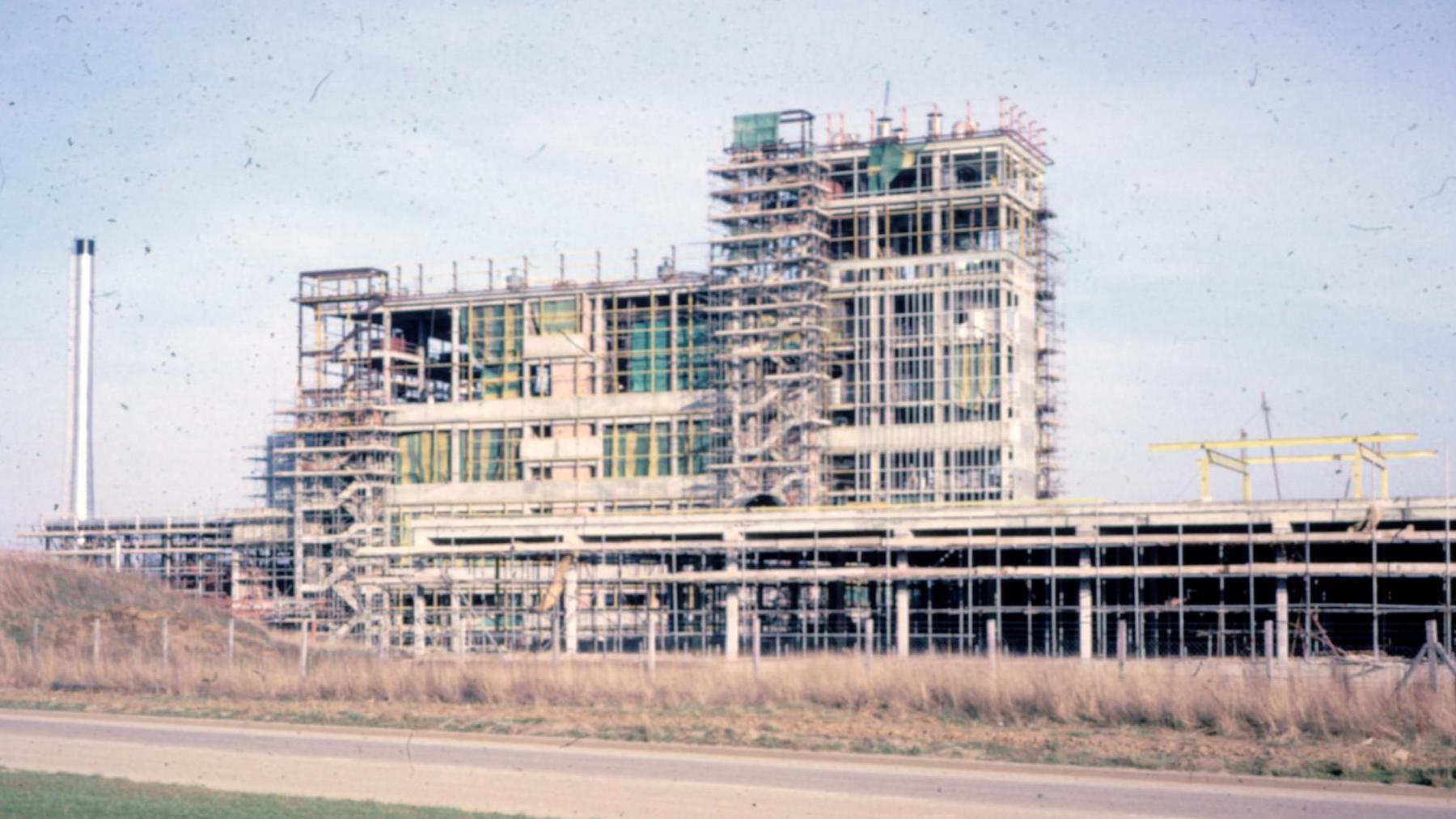

In the early years, the factory sat amongst fields as an icon of the town's ongoing shift from agricultural hub to industrial powerhouse.

Chris Moon, who's father worked at the factory, said: "I remember when I was little, the air raid warning siren, that makes that horrible noise, was on top of the factory.

"It used to go off to let the families in and around the town know that the change of shift was coming, which was really amazing."

The site first opened in Banbury in 1964

The Barratts, who spent a combined total of almost 50 years working at the site, said it had been "very hard, but it gave us a good standard of living".

Mrs Barratt said GF would "really look after people", adding: "If you had any problems, they would do their best to help you out.

"One bloke had a big gambling problem and he was in big debt financially, so what they did was they sacked him, gave him his pension, and then reemployed him - so he could pay them off," she said.

"That's how kind it was then."

Mr Barratt said it had been "good fun" to work at the factory.

"We used to do our job, but we did also used to have a proper laugh," he added.

His wife of more than 60 years said: "It was a job for life, really - they were always pretty fair and they paid good money.

"We got to do a lot of things we hadn't thought doable - it gave us all of very good lives."

The factory initially sat among green fields

By 1982, my dad had followed in his father's footsteps and joined the the General Foods lineage.

Explaining how he ended up working at the factory, he said: "I put in for a job and I got it because they used to take on family members.

"Over the past 60 or so years my dad worked there, my aunt and uncle worked there, my sister worked there, my cousins worked there - they really looked after families.

"Although you had to be careful what you said about someone, because you'd say something and the person you'd be talking to would turn around and say 'oi, that's my husband you're on about'."

During the late 1980s the plant was rebranded to Kraft

A few years later, during the late 1980s, the plant underwent its first of many rebrands as General Foods merged with Kraft - best known products such as Philadelphia Cream Cheese.

Mrs Barratt said the merger "changed" the place because "you lost the personal touch".

"It became more or less just about the business," she said.

It was during Kraft's period of ownership that the plant became a hub for the US company's development of new products - with its most successful creation being Tassimo.

The instant pods, which used barcodes to calculate the right amount of water, brewing time, and temperature for the specific beverage, launched in 2004.

Dessert production ended at the factory in 2005

A year after the launch of Tassimo, the sale of Kraft's dessert assets to Premier Foods brought an end to 40 years of sweet-treat production at the Banbury plant.

Mr Moon, who worked in the department before becoming the plant's union branch secretary, said: "You'd walk in for a 6am shift and you could smell the jellies and the cream topping, and then you'd smell the coffee - it was Banbury in a nutshell."

He said the plant had been "on a decline" since dessert production came to an end.

"There was no investment in infrastructure or within the plant itself - the writing has been on the wall since then," he said.

Coffee production at the site ended in 2023

Kraft's food production split in 2011, and the factory underwent another rebranding under the short-lived Mondelez banner.

Just four years later, JDE acquired Mondelez's coffee assets - including the plant.

JDE's reign was tumultuous and marred by widespread industrial action in 2020 and 2021.

The strike came after the Dutch company proposed plans to fire and rehire much of the workforce on less favourable contract terms. Workers later agreed a deal to avoid the proposal.

Unite's regional officer Mick Pollock said the "bad taste and smell" from the process had "thankfully dissipated" since the strike action.

The old Bird's logo still adorns the gates at the front of the site

Two years after the strikes, coffee production at the plant ended after almost 60 years - with last month's further development that the factory would shut completely not coming as a surprise for those involved.

Everyone I spoke to for this piece had left the factory prior to June's announcement, but about 160 current employees had not - meaning they will be left jobless, many after decades of service at the factory.

Mr Pollock said the workers had done a "phenomenal job" since the last bout of redundancies following the end of production two years ago.

But he added that the union "couldn't compete against the fact that systematic owners have not put the money into the infrastructure that they should have".

The factory first opened under the General Foods banner in the 1960s

During its six decades at the heart of the town, the factory had a lasting impact on Banbury and its people.

"It's always been part of me, it's always been in my blood and it's part of the town's DNA," Mr Moon said.

My dad, Michael, ended up working at the plant for 40 years and said the decision to close it was "terrible news"

"I can't say a bad word about the place because it's given me and our family a great way of life," he said.

"Even with all of those Christmases and birthdays I missed because I was working - in the long run it worked out right."

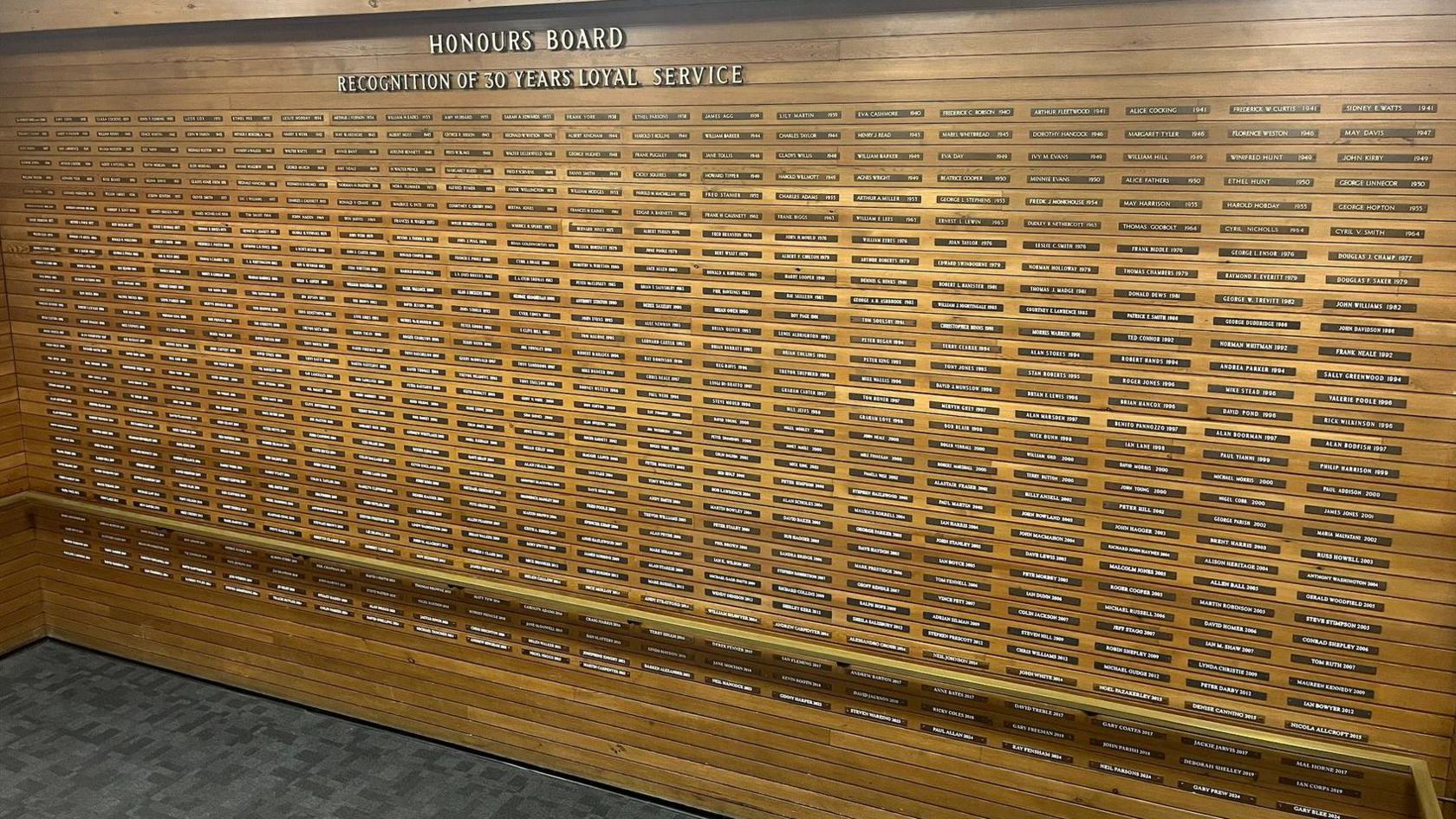

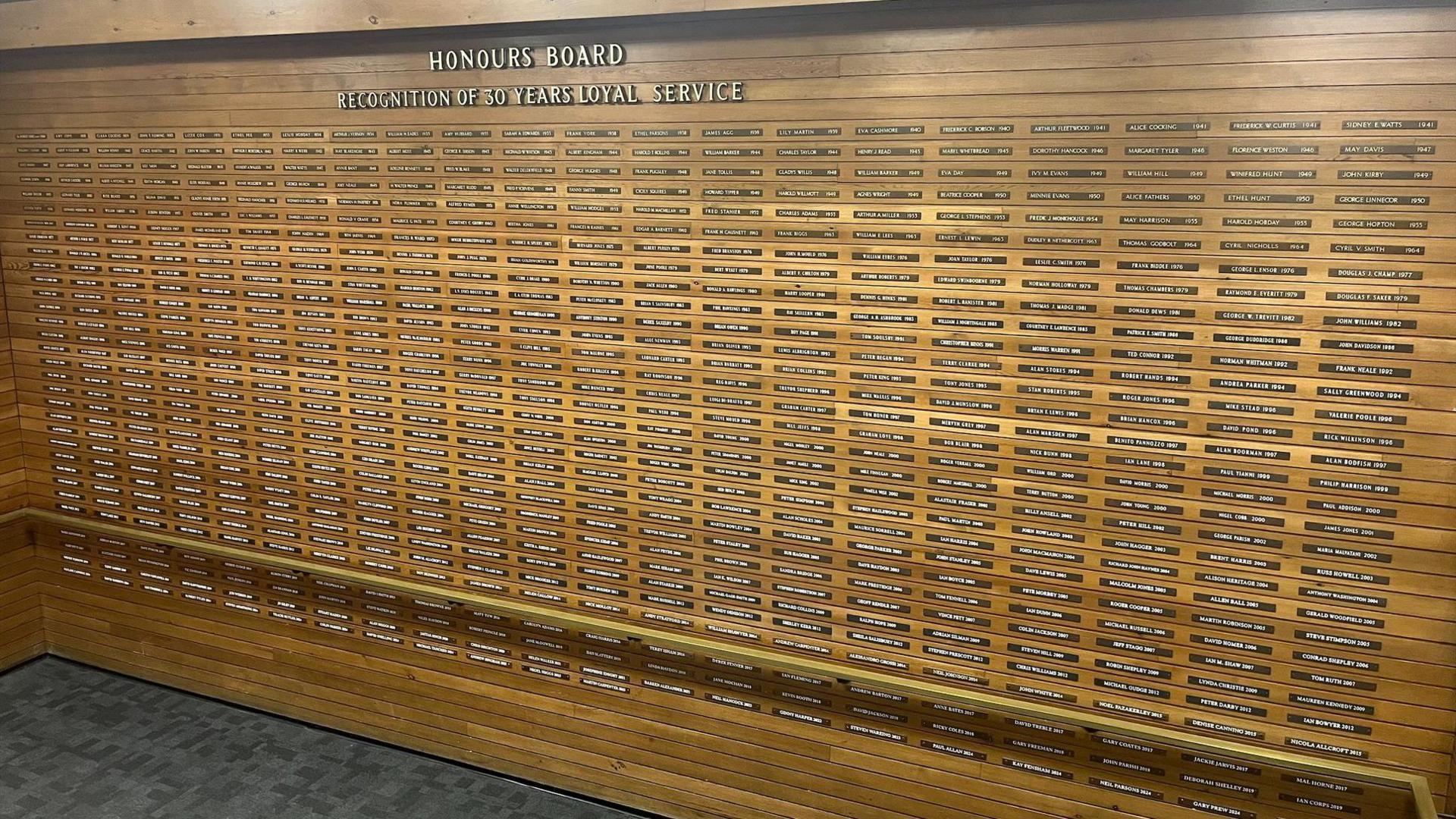

An honours board at the factory has more than 600 names on it

For many, there is no greater symbol of the factory's impact and longevity than its honours board, which is adorned with more than 600 names of former employees who spent 30 or more years of their working life at the site.

"That's a testament to the factory because there wasn't a big turnover of employees - it was the place to be," Mr Moon said.

But for those who never entered the factory, the lasting image of it will be the immense metal structure rising from the Oxfordshire hills as a beacon of home amongst an ever-growing sprawl.

Jo Mobley, whose father worked at the plant, said: "Coming back that was the first thing you saw - the smoke coming out of the factory - and then you knew you were home."

Soon, the plant will no longer dominate the Banbury's skyline as it has for the past 60 years, but its impact on the town will last for generations to come.

Get in touch

Do you have a story BBC Oxfordshire should cover?

You can follow BBC Oxfordshire on Facebook, external, X (Twitter), external, or Instagram, external.

Related topics

- Published2 July

- Published18 June

- Published17 June