Search for Jigsaw Murder families after bones find

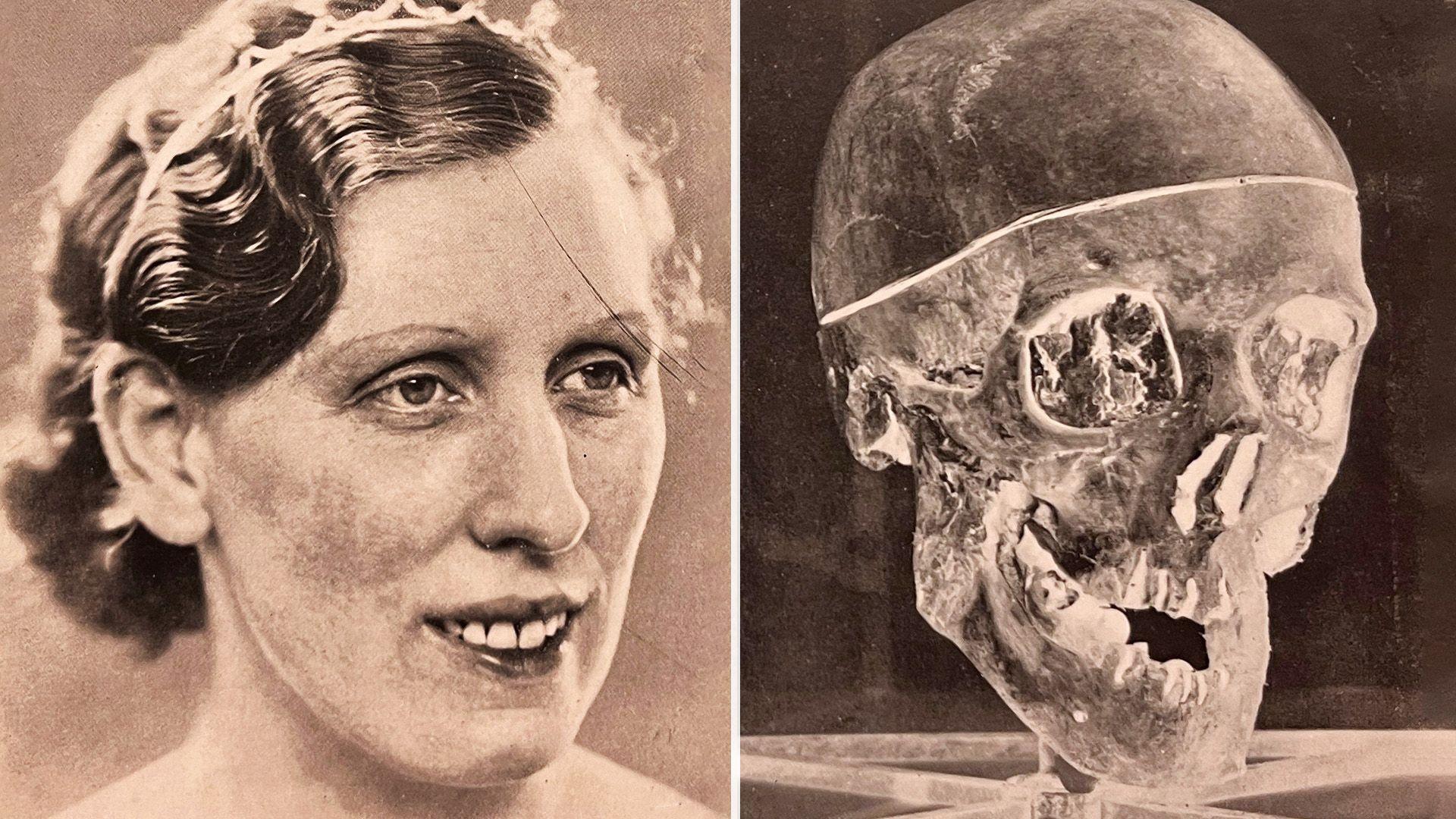

An X-ray of Isabella Ruxton's skull was a crucial piece of evidence in the case

- Published

A search has been launched for the families of two women killed 90 years ago in the Jigsaw Murders, after their skulls were rediscovered in a university storeroom.

The deaths of Isabella Ruxton and Mary Rogerson, whose bodies were found in Moffat, Dumfries and Galloway, made headlines around the world in 1935.

The case broke new ground in forensic science when Edinburgh University helped build evidence against Dr Buck Ruxton, who was hanged for his wife’s murder.

The university has now discovered that the skulls and other bones are still in its archive. It is trying to trace the women's relatives to ask if they wish these to be returned.

Professor of anatomy Tom Gillingwater said: "We want to do the right thing by Isabella and Mary and, if appropriate, return them to their families so they can be laid to rest."

The university decided to issue a public appeal through the BBC instead of approaching the families privately, because it is not known whether Isabella and Buck Ruxton’s three orphaned children were ever told that their father had been hanged for murdering their mother.

The two women were reported missing by Mary Rogerson's family

The killings - which became known as the Jigsaw Murders - took place in Lancaster in September 1935.

Newspaper reporters flocked to Dumfries and Galloway after dismembered and disfigured human remains were discovered beneath a bridge over a stream near Moffat.

The remains were sent to Edinburgh University, where forensic scientists and colleagues from Glasgow University pieced together the body parts.

As they carried out their gruesome task, another investigation was under way in Lancaster, north west England.

Dr Buck Ruxton had given various explanations for the disappearance of his wife Isabella and their nursemaid Mary Rogerson.

The popular GP had been jealous of his wife's friendship with other men.

She had accused him of domestic abuse before she vanished but local police had taken no action.

Mary and Isabella were reported missing by Mary's family, not by Ruxton.

Ruxton stood trial five months after the bodies were found

Investigators in Scotland made the link between the two women and the remains which were found near Moffat.

The bodies still had to be identified beyond doubt and their killer, who was known to have experience of surgery, had taken great care to make that as difficult as possible.

Ruxton’s efforts to avoid justice were defeated by groundbreaking forensic techniques which confirmed the remains were those of Isabella and Mary.

The identification was crucial to the prosecution case in what was described as "the trial of the century”.

Ruxton went into the dock at the Assize Court in Manchester five months after the bodies were found.

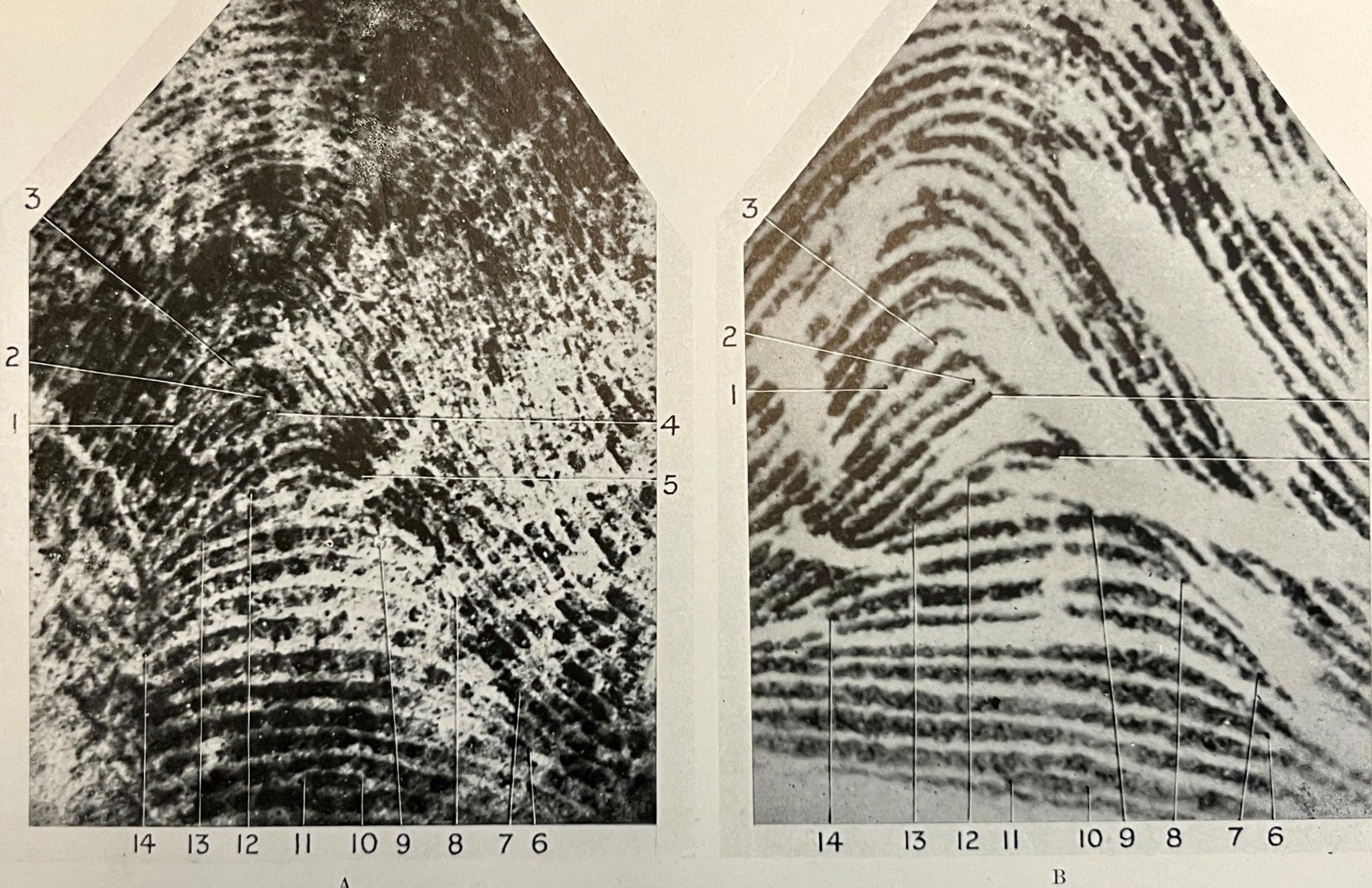

A new technique for analysing fingerprints was used to identify Mary Rogerson

The jury was shown an image of Isabella that the scientists had superimposed on an X-ray of one of the skulls from the ravine - the first time such evidence had been used in court. They were a chilling match.

The trial was told that a new technique for analysing fingerprints had been used to identify Mary.

The scientists had also studied insects found on the bodies to establish the date of their deaths.

Ruxton was convicted of murdering his wife. He had also been accused of killing Mary but the charge was dropped before the trial.

Two months after he was found guilty, huge crowds gathered outside Manchester's Strangeways Prison when he was executed by hanging.

Crowds gathered outside Strangeways Prison when Ruxton was executed

Former assistant chief constable Tom Wood has written a book on the case, entitled Ruxton: The First Modern Murder.

"It was one of the most important criminal investigations of the 20th Century, not because of the horror of the case and the dismemberment of the bodies, but because of the forensic science," he said.

"Put simply, anything before the Ruxton case was ancient history. Anything after the Ruxton case is modern, integrated, forensic science-led investigation.”

In the decades that followed, the women's bones were held in Edinburgh University's huge anatomical collection, stored in boxes in a vault alongside evidence from the case.

The assumption is that they were retained for further medical research.

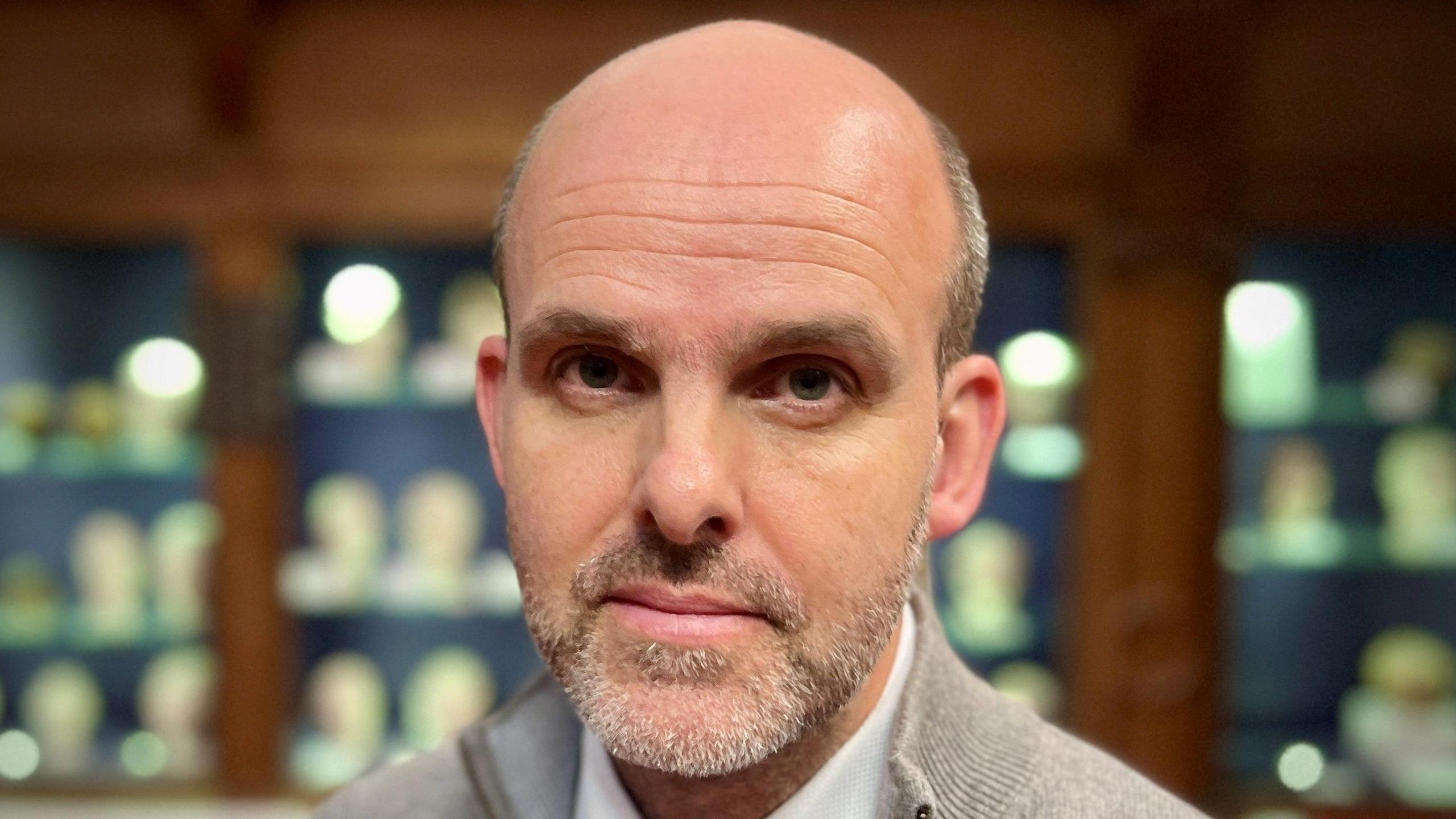

Tom Wood says it was one of the most important criminal investigations of the 20th Century

Prof Gillingwater and Tom Wood both argue that this decision should be viewed in the context of the ethical standards of the time.

"If you're asking me if I would have done the same thing with my 21st Century lens, absolutely not," said Prof Gillingwater.

"But at the time what those scientists did in this investigation was remarkable and revolutionary."

Mr Wood believes it is unlikely the women’s families knew they were holding funerals without all of their loved ones’ remains.

"I can understand why they did it. These were men of science,” he said.

“These were men who were determined to improve criminal investigation and they would have used these body parts to do that.

“This was not some cruel disregard. These remains were kept for the advancement of science."

Isabella and Mary’s remains had been kept in a university storeroom

Prof Gillingwater says the remains were "found or re-found" after receiving an inquiry from an academic in the Netherlands with an interest in the history of forensic medicine.

“The overriding feeling was that OK, these are not perhaps being treated with the full level of care and respect that we would want,” he said.

The university was told by the Scottish government that its possession of the remains was legal – but it decided to establish whether they should be returned to the women’s families.

However, that created another dilemma.

Isabella and Buck Ruxton’s three young children were fostered and it is not known if they were ever told how their parents died.

Mary Rogerson is known to have relatives in the Morecambe area, while Isabella's sister Jeannie Nelson was living in Edinburgh at the time of the murder.

Prof Tom Gillingwater has asked any relatives to contact the university

After consulting experts on ethics, the university decided to issue an appeal through the BBC.

"The guidance was very clear, that we should not be approaching people who may not be aware that they were related to these ladies," said Prof Gillingwater.

"If there are any relatives of Isabella or Mary who believe that they would like to have the remains returned to them, we would be delighted to talk to them about what the next steps might be."

The university says any discussions will be held in strictest confidence and the families should not feel under pressure to come forward.

They can make contact through a section on the university's website, external.

Related topics

- Published15 March 2023