Buck Ruxton: The Jigsaw Murders case where forensics were key

- Published

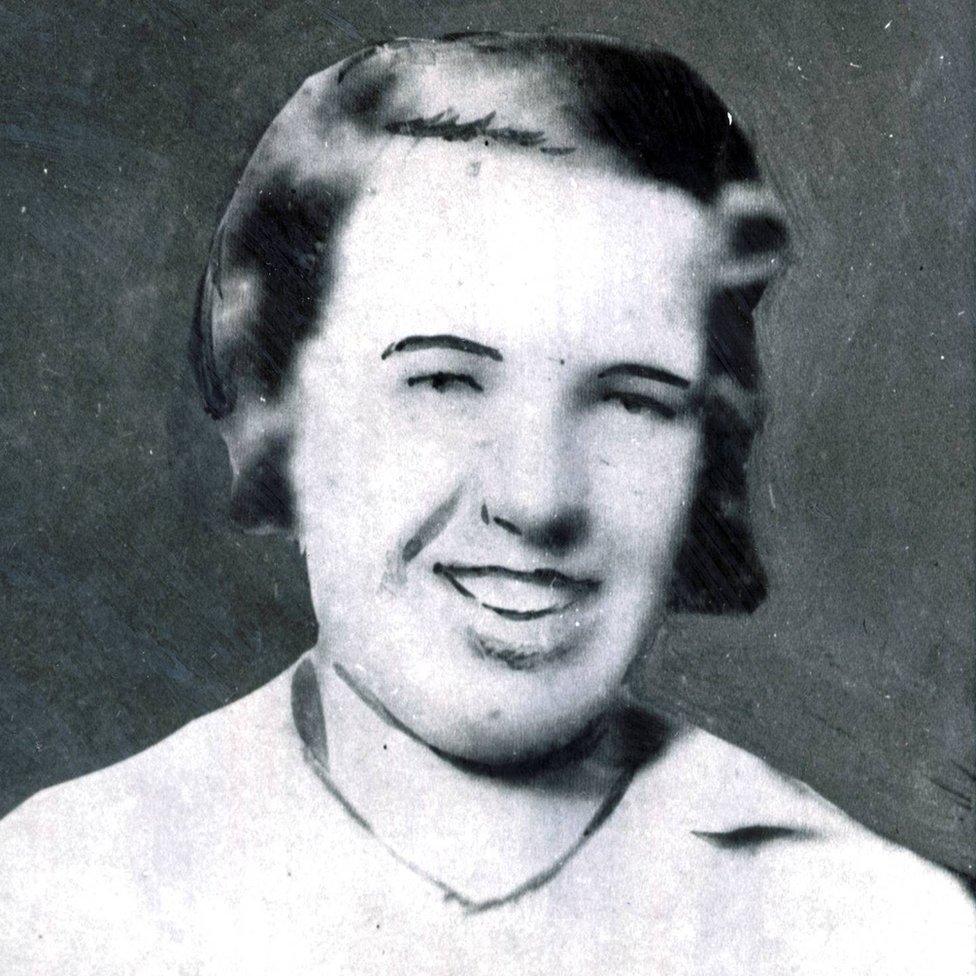

Dr Buck Ruxton was sentenced to death for his crimes

It was one of the highest profile murder cases of the 1930s and also a pioneering one in terms of how the killer was brought to justice.

The downfall of Lancashire doctor Buck Ruxton began after human remains were found under a bridge near Moffat.

A painstaking investigation saw him sentenced to death for the murder of his common-law wife and housemaid.

A new exhibition is set to open in Moffat museum highlighting the area's role in solving the notorious crime.

Janet Tildesley is a volunteer and trustee who has helped to put it all together and explained why the case - dubbed the Jigsaw Murders - still fascinated people nearly 90 years later.

Buck Ruxton drove north past Moffat to dump the remains

After murdering the two women in September 1935 in Lancaster, Ruxton dissected the bodies and wrapped them in newspaper, old clothes and sheets and drove north.

That is where Moffat comes into the story as he found the spot north of the town he thought was remote enough for his crime to go undiscovered.

"He threw the body parts over a bridge into a ravine," Ms Tildesley said.

"The body parts were found a couple of weeks later by a visitor when she noticed them and got the police involved.

"That's when, I guess, the case really started."

Janet Tildesley has been involved in putting together the exhibition on the Buck Ruxton case

The initial job was simply to try to identify who had been killed.

"They thought, originally, that it was a man and a woman and gradually began to piece it together," said Ms Tildesley.

"What was important about the case was its use of forensics - it was one of the earliest cases to use forensics - the evidence in this case was almost wholly circumstantial.

"First of all, they had to prove who these body parts belonged to and then to, if you like, assign a murderer to the murder."

A team led by Prof John Glaister of the University of Glasgow - involving experts in a range of areas - worked on the investigation.

They used pioneering techniques to get fingerprints from one of the badly damaged bodies and also superimposed photographs onto one of the skulls they had found to help identify one victim.

Another significant piece of work was their use of entomology to establish the time of death "really conclusively" based on the life-cycle of maggots.

The exhibition in Moffat will also highlight the role of local police officer, Sgt Robert Sloan, which Ms Tildesley said had been "really underestimated".

He was first on the scene after the bodies were discovered.

The case provoked huge public interest when it went to court

"He did not seem to be overawed by what he saw and he secured and preserved the crime scene," said Ms Tildesley.

"Nowadays, of course, that's what people would do, police are trained and there's all kinds of tape that they have and body suits - but he had none of that."

His notes and map of the scene were vital as was the fact that he carefully handled the newspaper in which some of the remains were wrapped.

"They were really significant because later on in the process when these were dried out, they were able to identify which newspaper it was, which date it was, and the fact that this was a limited-circulation newspaper which was of great importance," she explained.

"This was a real first. The trial was all about forensic specialist evidence and the fact that it led to Buck Ruxton's conviction really engendered huge public and professional trust in the whole development of forensics."

Maid Mary Jane Rogerson is thought to have witnessed the first murder and been killed

Ruxton's version of events also fell apart while the evidence against him was being gathered.

His maid Mary Jane Rogerson had been reported missing, then he reported his wife missing as police north and south of the border worked together to make their case.

Ms Tildesley said he was, in layman's terms, "beginning to unravel."

"His story was changing and he was beginning to get quite distressed," she said.

Huge crowds gathered on the day of Buck Ruxton's execution

The evidence gathered in Moffat helped to convict Ruxton of the murder of Isabella Kerr, his common-law wife, and Ms Rogerson and he was sentenced to death.

"The story seems to be that she [Ms Kerr] came back very late one night and he was just incandescent with jealousy and rage, and he strangled her," said Ms Tildesley.

"The maid was there and she came upon it and he murdered her as well.

"I think it was a crime of passion and he then panicked.

"It's a macabre story, you know, ghastly in parts, hugely interesting in parts, hugely significant in terms of forensics - and terribly, terribly sad."

The exhibition opens at Moffat Museum on 1 April and runs until the end of October.