Huge COP29 climate deal too little too late, poorer nations say

- Published

Richer countries have promised to raise their funding to help poorer countries fight climate change to a record $300bn (£238bn) a year, but the deal has come under criticism from the developing world.

The talks at the UN climate summit COP29 in Azerbaijan ran 33 hours late, and came within inches of collapse.

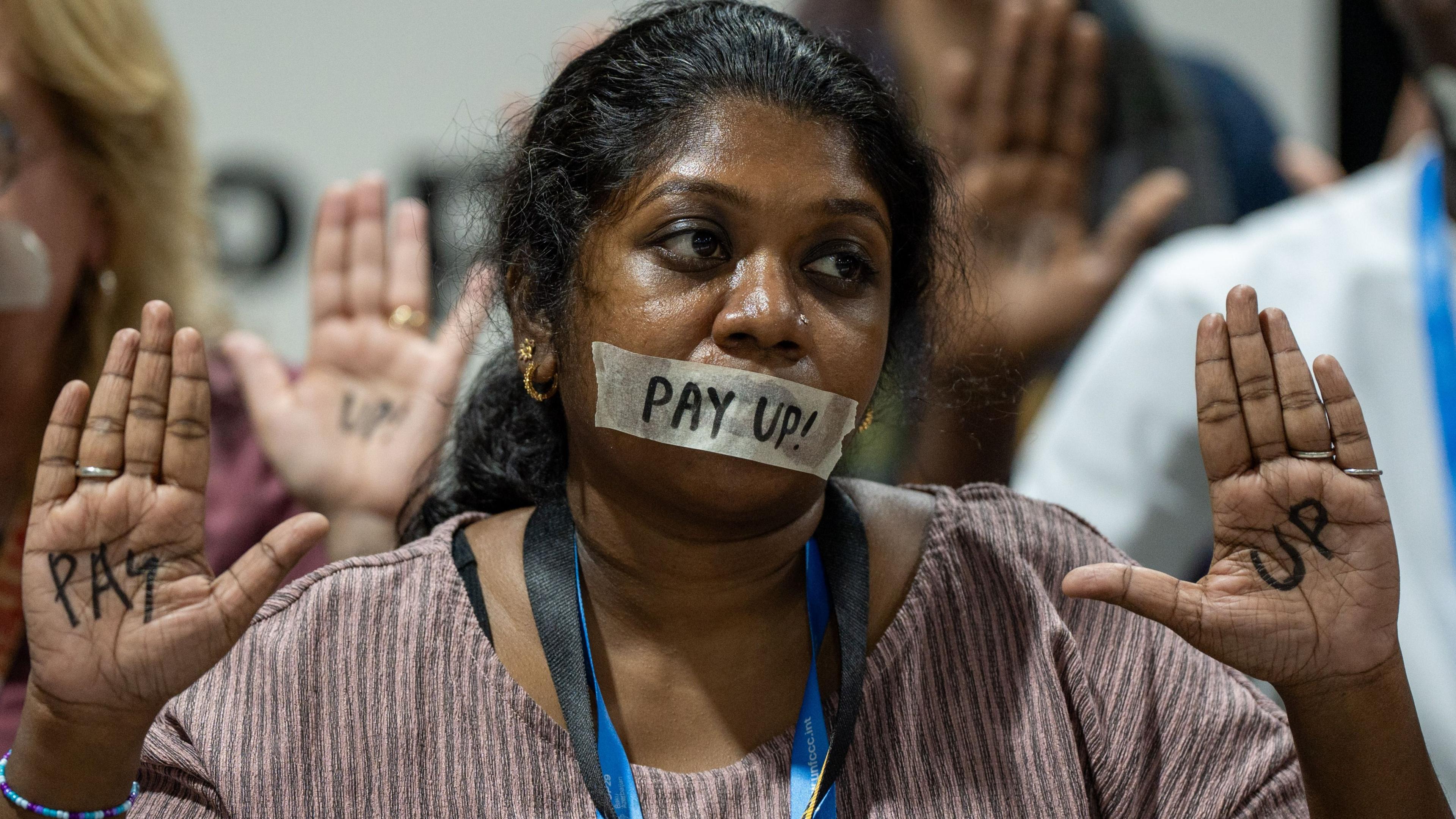

The agreement falls well short of the $1.3tr developing countries were pushing for. The African Group of Negotiators described the final pledge as "too little, too late", while the representative from India dismissed the money as "a paltry sum".

But after two weeks of often bitter negotiations in the Azerbaijani capital, Baku, poorer nations did not stand in the way of a deal.

The promise of more money is a recognition that developing nations bear a disproportionate burden from climate change, but also have historically contributed the least to climate change.

The head of the UN climate body, Simon Stiell, conceded that the agreement was far from perfect.

"No country got everything they wanted, and we leave Baku with a mountain of work still to do," he said in a statement.

The deal was announced at 03:00 local time on Sunday (23:00 GMT on Saturday). As well $300bn (£238bn) a year by 2035, it promises efforts to raise $1.3tn a year from both public and private sources by that date.

The announcement was met with cheers and applause, but a furious speech from India showed that intense frustration remained.

"The amount that is proposed to be mobilised is abysmally poor. It's a paltry sum," Leela Nandan told the conference.

The chair of the Alliance of Small Island States, Cedric Schuster, said: “Our islands are sinking. How can you expect us to go back to the women, men, and children of our countries with a poor deal?”.

The funds pledged are expected to help poorer countries move away from fossil fuels and invest in renewable energy such as wind and solar power.

There was also a commitment to tripling the money going towards preparing countries for climate change. Historically, only 40% of the funding available for climate change has gone towards this, external.

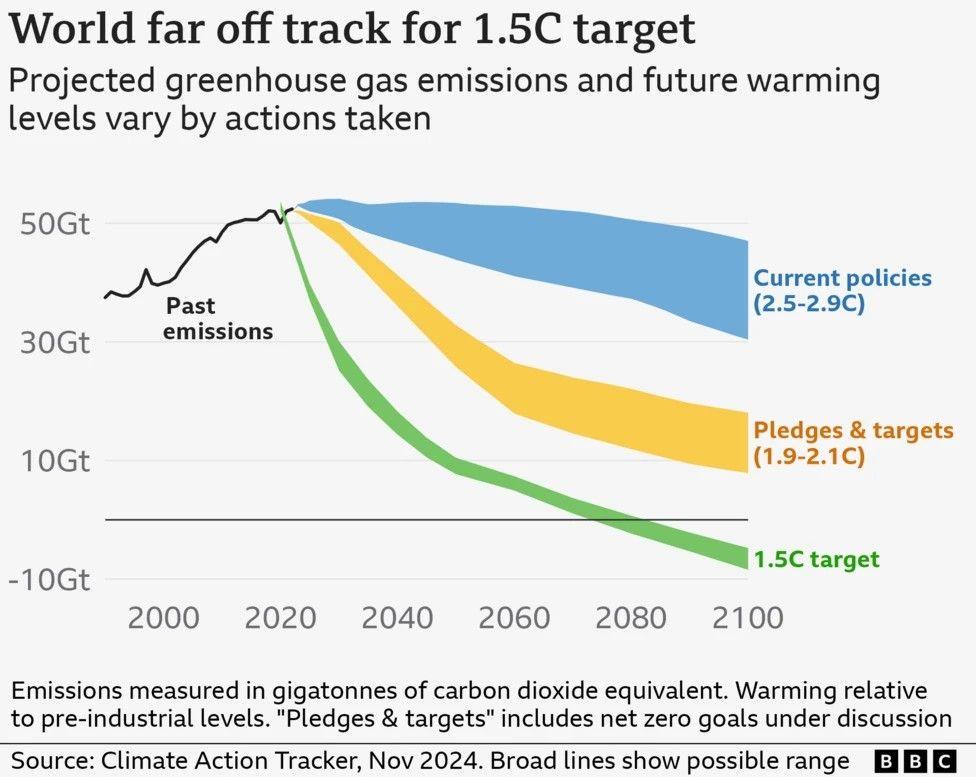

This year - which is now "virtually certain" to be the warmest on record - has been punctuated by intense heatwaves and deadly storms.

Climate charities have criticised the agreed deal.

Jasper Inventor, head of the COP29 Greenpeace delegation, called the deal "woefully inadequate" and said "reckless nature destroyers" were being protected by "every government's low climate ambition".

WaterAid described the deal as a "death sentence for millions", while a spokesperson for Extinction Rebellion said COP29 had "failed".

Friends of Earth head of policy Mike Childs said that in terms of climate leadership, the planet is still "light years away from where we were" at last year's meeting in Dubai.

"These latest international talks failed to solve the question of climate finance," he said.

"Instead they have again kicked the can down the road."

The opening of the talks on 11 November was dominated by the election of US President Donald Trump, who will take office in January.

He is a climate sceptic who has said he will take the US out of the landmark Paris agreement that in 2015 created a roadmap for nations to tackle climate change.

“For sure it brought the headline number down. The other developed country donors are acutely aware that Trump will not pay a penny and they will have to make up the shortfall,” Prof Joanna Depledge, an expert on international climate negotiations at Cambridge University, told the BBC.

Reaching this deal is a sign that countries are still committed to working together on climate, but with the largest economy on the planet now unlikely to play a part, it will become harder to meet the multi-billion dollar goal.

“The protracted end game at COP29 is reflective of the harder geopolitical terrain the world finds itself in. The result is a flawed compromise between donor countries and the most vulnerable nations in the world,” said Li Shuo from the think-tank Asia Society Policy Institute.

UK Energy Secretary Ed Miliband stressed that the new pledge did not commit the UK to come up with more climate finance but it was actually a “huge opportunity for British businesses” to invest in other markets.

“It is not everything we or others wanted but it is a step forward for us all,” he said.

In return for promising more money, developed nations including the UK and the European Union wanted stronger commitments by countries to reduce use of fossil fuels.

Despite their hopes that the agreement struck at the talks in Dubai last year to “transition away from fossil fuels” would be strengthened, the final proposed agreement only repeated it.

For many nations this was just not good enough, and it was rejected - it will now have to be agreed next year.

Countries that rely on oil and gas exports reportedly put up a strong fight in negotiations to stop further progress.

“The Arab Group will not accept any text that targets specific sectors, including fossil fuels,” Saudi Arabia’s Albara Tawfiq said at an open meeting earlier this week.

Countries negotiated for almost two days straight to get the deal over the line

Several nations came to the talks with new plans to address climate change in their own countries.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer made a play for climate leadership on the world stage and pledged to reduce UK emissions by 81% by 2035, which was celebrated by many as an ambitious goal.

The host nation, Azerbaijan, was a controversial choice for climate talks. It says it wants to expand gas production by up to a third in the next decade.

Brazil is seen as a better choice to host next year’s climate summit, COP30, in the city of Belém because of President Lula’s strong commitments to climate change and reducing deforestation in the globally important Amazon rainforest.