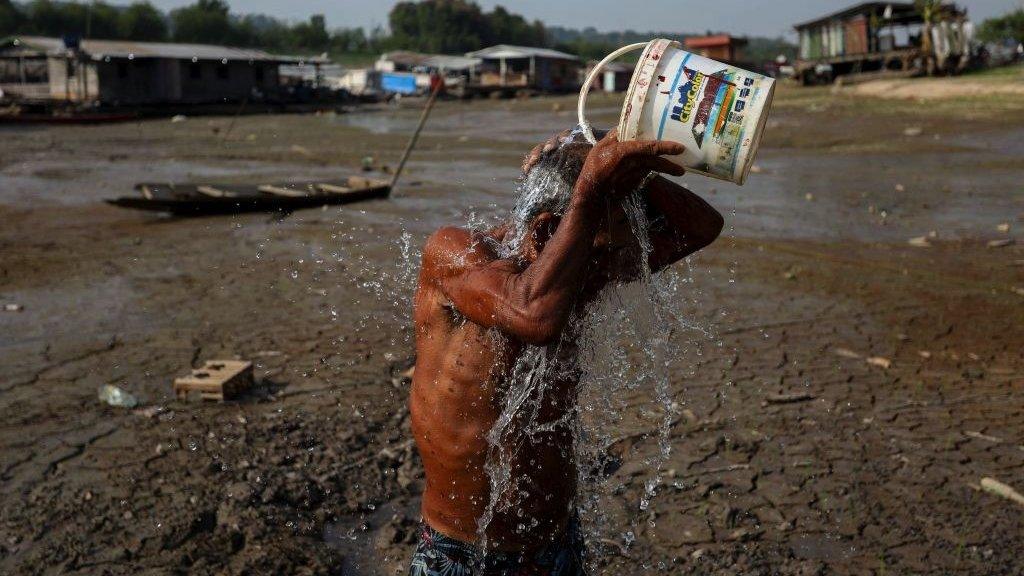

Drought leaves Amazon basin rivers at all-time low

People living along the dried-up rivers have had to carry drinking water on their shoulders

- Published

Water levels in many of the rivers in the Amazon basin have reached their lowest on record amid a continuing drought, the Brazilian Geological Service (SGB) says.

The Madeira river, a major tributary to the Amazon, had fallen to just 48cm in the city of Porto Velho on Tuesday, down from an average of 3.32m for this day, official data showed, external.

The Solimões river has also fallen to its lowest level on record in Tabatinga, on Brazil's border with Colombia.

Brazil's natural disaster monitoring agency Cemaden has described the current drought as the "most intense and widespread" it has ever recorded.

It is particularly concerning because it has worsened relatively early in the Amazon’s dry season, which typically runs from June to November.

That suggests the situation in the Amazon may not significantly improve for some months in a region which is critical in the fight against climate change, as well as being a rich source of biodiversity.

The links between drought and global warming are complicated, but climate change can play a role in worsening dry conditions in two main ways.

Firstly, the Amazon basin is typically receiving less rainfall than it used to between June and November as climate patterns change.

Secondly, hotter temperatures increase the evaporation from plants and soils, so they lose more water.

In 2023, the Amazon basin suffered its most severe drought in at least 45 years – which scientists at the World Weather Attribution group found had been made many times more likely by climate change.

Last year, the drought was also worsened by the natural weather pattern known as El Niño, which tends to make the Amazon warmer and drier than normal as well.

El Niño has since ended, but the dry conditions have persisted.

Another factor in Amazon droughts is deforestation. Around one-fifth of the rainforest has been lost over the last 50 years, for example to make way for agriculture.

These trees provide resilience against drought because they help to increase rainfall by releasing moisture back into the air from their leaves. Without them, the Amazon is more vulnerable.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has pledged to halt deforestation completely by 2030.

But the current drought – which has helped fires to spread – highlights some of the challenges of limiting further forest loss.

Forest fires spread quickly through the already dry vegetation

The low water levels in the region's main rivers are also severely impacting the lives of local people, who rely on them for navigation.

According to Cemaden, as of last week there were more than 100 municipalities which had not seen any rain for more than 150 days.

Residents of Manacapuru, on the banks of the Solimões river, said they were struggling to get vital supplies, including food and drinking water, to the city.

"We anchored the boat here, and it was stuck on dry land the next day. We had no way to move it," fisherman Josué Oliveira told Reuters news agency.

"Nothing will get through," another fisherman explained.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to get exclusive insight on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC's Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week.

Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.

- Published24 January 2024

- Published26 December 2023

- Published12 October 2023