'Misinformation is creating a moorland tinderbox'

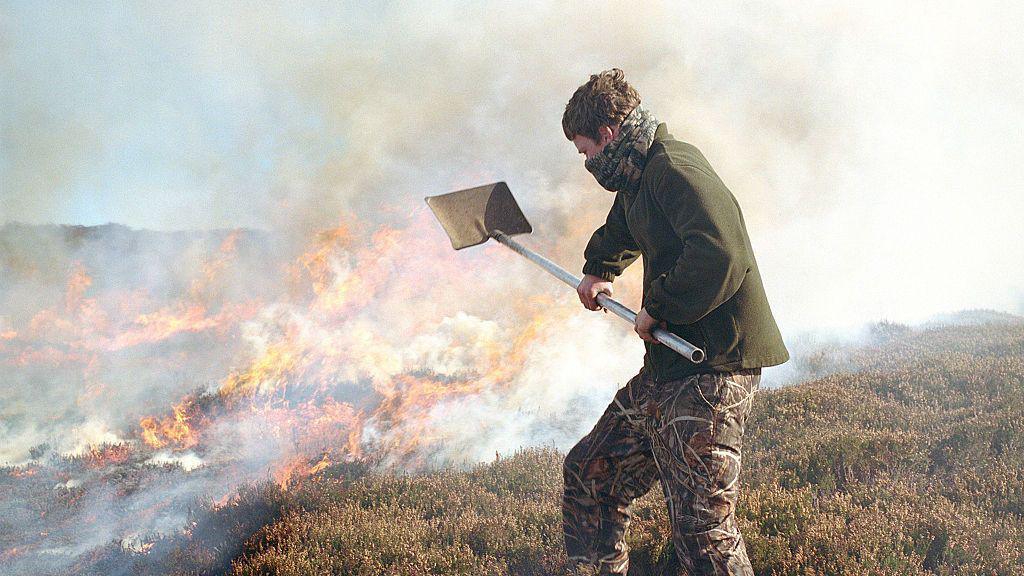

Gamekeepers have traditionally managed moors through a process called controlled burning

- Published

Moorland fires have raged across Yorkshire this summer, with incidents at Langdale Moor in the North York Moors National Park and Marsden Moor near Huddersfield.

Gamekeepers and rural landowners often manage the land - traditionally used for grouse shooting - through a controversial process known as controlled burning.

They say the process is not just for managing grouse populations, but also for preventing wildfires.

They argue that burning the old, dry vegetation in a controlled manner prevents a build-up of flammable material that can make wildfires worse.

Environmentalists say the process can get out of hand, inadvertently causing wildfires and destroying the natural wetland state of peat bogs, which store carbon and are home to many species of birds and insects.

Creating grouse habitat

Every year on August 12 – known among shooters as the Glorious Twelfth – groups of hunters take to the moors to shoot red grouse for sport and food.

According to the British Association for Shooting and Conservation, grouse shooting generates £100m for local economies, and more than 40,000 people take part in the activity annually.

Red grouse eat heather, preferring newer, greener shoots, which is one of the reasons gamekeepers carry out controlled burns, creating space for new growth.

Country Land and Business Association chartered surveyor Robert Frewen manages moors for clients. He explains how the process works.

"They're burning off the top layer of vegetation and nothing else.

"I've seen an example where a Mars bar in its wrapper has been put on the peat and then a keeper has done a controlled cool burn over the top of it and the Mars bar, including the wrapper, is still intact after it," he says.

"If the keeper sets fire to the peat, he's made a bad mistake and it very rarely happens."

Burning is legally restricted to the spring and autumn, with keepers looking for a dry day when there has been rain in the preceding few days so the underlying peat is wet but the top vegetation has dried off, he says.

"Then they will go out with a team and start a small fire. You'll have two of them moving up the side of it to make sure it doesn't get very big and then they'll go around the end and put it out.

"They're looking to burn little patches in a mosaic no more than 10 yards wide, and maybe 15 and 20 or 30 yards long.

"You're looking to create a mixed habitat where you have some recently burned patches, some middle-aged heather, which is good for grouse to eat and then some long heather where it's good for them to nest and to hide from predators."

Keepers say they manage the fires by burning a thin layer of old vegetation

Earlier this year, the government announced a consultation on heather burning legislation.

It is expected the consultation will lead to stricter regulations over a wider area of moorland, including reducing the required peat depths in the areas that can be burned. Owners are already required to apply for licences to carry out burning.

The government says 80% of England's peatlands are degraded, with "rotational burning being a contributory factor in upland regions". It says burning should be seen as a "last resort".

The RSPB says the moors should be returned to "natural wetland".

Tom Aspinall, RSPB senior policy officer for uplands, says peatlands are or "should be" inherently wet.

"Unfortunately the legacy of drainage and burning, and in some places industrial air pollution from towns and cities, particularly from the industrial revolution, has degraded peatlands to the point that they're much drier, so they are now more susceptible to fire," he says.

"On the sites we manage we restore those habitats back to what they ought to be, which is a wet functioning peatland that will be forming new peat."

He says peatland landscapes are the best means of mitigation against the risks of fire because they hold water.

"The problem with burning to try and reduce fire risk is that you put yourself in the perpetual cycle of increased fire risk, because the vegetation that grows after a burn is generally heather and heather is an oily plant, so it's very volatile.

"When you re-wet or diversify, you've got a different range of plants so you break up that continuous fuel and you can affect the ability of fires to spread."

Dove Stone Nature Reserve in Greater Manchester is a rewetted area managed by the RSPB

University of York associate professor Andreas Heinemeyer has studied moorland ecology across the UK for 15 years.

He says the false "culture war" between those who are pro-burning and those against is putting everyone at risk by making wildfires more likely.

"Wildfires will happen but managed heather will dramatically reduce their impact and allow easier control," he says.

"We urgently need an unbiased and robust evidence assessment.

"Too much misinformation is creating a high-risk heather moorland tinderbox."

He says suggested legislation changes are based on false, simplistic claims.

"The evidence clearly says there are lots of false and misleading claims about burning," he says.

"Every site is different. That's ecology. You can't just have a blanket approach. You need to consider how wet a site can be.

"Re-wetting and restoring peatlands is good but it won't necessarily make them resilient to wildfires, especially under climate-change scenarios, which clearly point out that lots of heather might still be there."

He says fires are inevitable and experts need to consider how to manage the landscape to get the best for everyone.

"A mosaic of management with different heather growth stages and vegetation composition will be more diverse," he says.

"What we see with no management is dominance of heather, reducing plant and animal diversity. Often trees and scrub establish, increasing fuel loads further and making peat even drier.

In response to Prof Heinemeyer's claims, a Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs spokesperson said: "We continue to work constructively with land managers to establish long-term, sustainable solutions to moorland management to maximise their future resilience."

Can both methods be used?

Richard Bailey, who has been a gamekeeper for more than 30 years, is a coordinator of the Peak District Moorland group.

He says the "increased polarisation between rewetting and managed burning" is not helpful.

"Everybody is on board with rewetting but we can use generational knowledge and experience to know where it doesn't work, and that is where we definitely need fire and fuel breaks in place, which is why we need to retain prescribed burning as a tool," he says.

"We've certainly seen an upturn in wildfires and that's through a number of sources.

He says tightening restrictions "will put far greater peatland areas under pressure because the management will not be available for land managers and there'll be bigger fuel loads, which potentially will set alight in wildfire situations".

He says it would be "folly" to imagine there will never be wildfires but by "managing vegetation on the ground" you can reduce the impact of large-scale fires.

"What we've got to avoid is the summer wildfires and at the moment with different methods and different ideas we are not doing that," he says.

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Yorkshire

Listen to highlights from North Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, catch up with the latest episode of Look North.

Related topics

Related stories

- Published21 March

- Published4 July

- Published14 August

- Published14 August

- Published10 April