Government borrowing, bonds and yields explained

- Published

Government borrowing, bonds and yields explained

You may have heard politicians and economists talking about government borrowing costs going up and then down again. Here’s a handy guide explaining what government borrowing, bonds, and yields all mean.

Governments borrow to cover the gap between their spending and income

Governments get most of their income from taxes, but often they will want to spend more money than taxes raise.

To cover that gap, they borrow money. They also borrow to pay for big projects, like new railways and roads.

A bond is an IOU from the government to investors, and a gilt is just another word for a bond

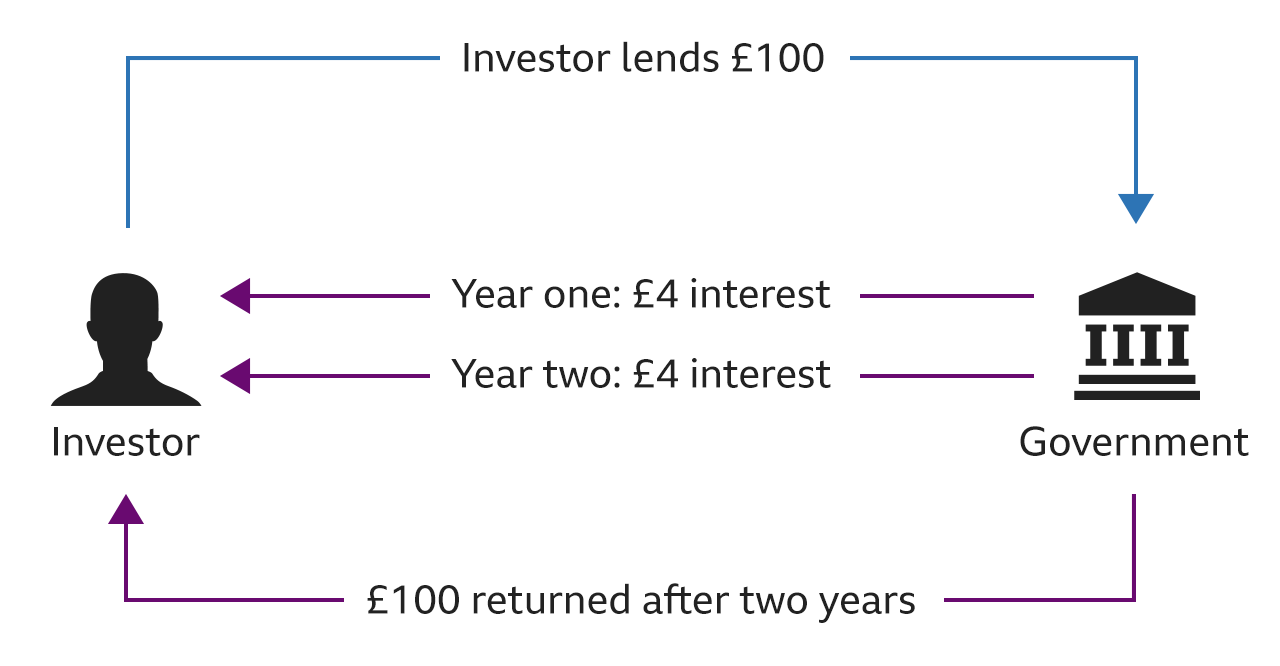

When a government wants to borrow money from investors, it sells them something called a bond, which is a loan the government promises to pay back at the end of an agreed time - say five, ten, or 30 years. The government will also make regular payments - which can be once every three months, six months, or year - to the investor.

In the UK, a government bond is called a gilt. It has other names in other countries.

Maturity is the date the government pays the investor back

On that day, the bond has matured and the investor gets the original value of the bond back. So, if someone buys a £100 bond from the government, they will get the £100 back if they hold the bond to maturity.

Yield is a way of figuring out return-on-investment

It is a percentage figure which tells you the amount of money someone would get each year if they bought a bond and held it until it matures.

You figure out the current yield by dividing the annual payment from the bond, which is the money the government gives the person who owns the bond over a year, by the full price paid for the bond.

For example, if someone pays the government £100 for a two-year bond which pays £4 a year, that means the yield is 4%.

Example: Two year bond with a 4% yield

Source: House of Commons Library

Bond prices can rise or fall based on demand, which then changes the yield

Higher interest rates and lower trust in a government’s ability to pay back a bond can drive down bond prices, as investors may sell their bonds if they feel they can get better deals elsewhere.

Lower prices mean higher yields. For example, paying the government £100 for a bond that pays £10 a year means a yield of 10%. But if that bond price drops to £80 and it still pays £10 a year, then the yield has gone up to 12.5%. And if the bond price goes up to £125 and it pays £10 a year, then the yield has gone down to 8%. When bond prices go up, yields go down and vice versa.

Government bonds are bought by lots of people, including funds and individual investors

Pension funds are some of the biggest buyers of government bonds because they are considered a safe investment. So some of your pension investment is very likely to be in bonds.

Banks - including central banks like the Bank of England - other governments, and investment funds are buyers too. You can also buy bonds yourself.

Related topics

- Published13 January

- Published20 June 2024

- Published19 December 2024