Zambia made education free, now classrooms are crammed

- Published

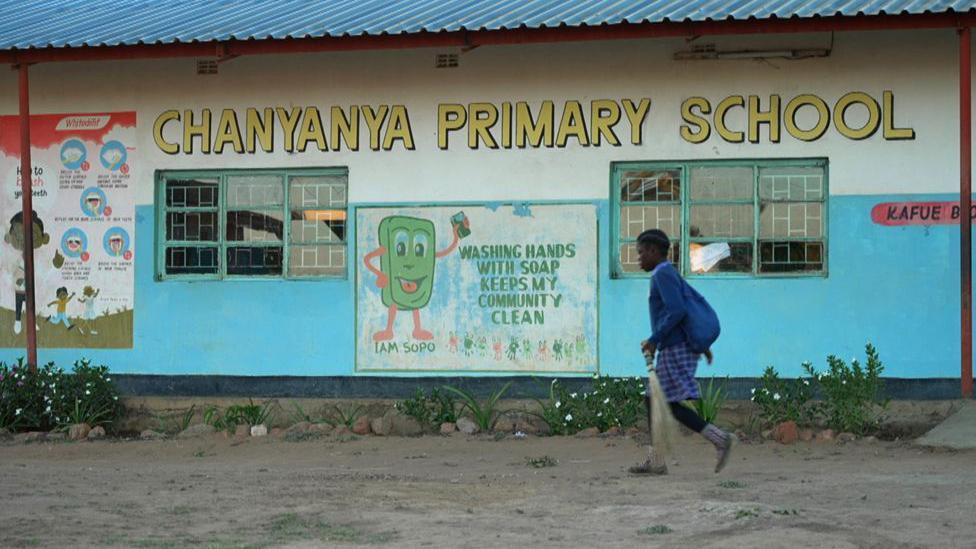

It’s 07:00 on a chilly winter morning and a group of students has just arrived at Chanyanya Primary and Secondary school, a little over an hour’s drive south-west of Zambia’s capital, Lusaka.

“You need to come early to school because there is a shortage of desks,” says 16-year-old pupil Richard Banda. “Two days ago I came late and I ended up sitting on the floor - it was so cold.”

His discomfort encapsulates the problem of a lack of resources and overcrowding that has come as a result of offering free primary and secondary school education here.

The school is in a compound made up of 10 classrooms arranged in a horseshoe shape around a playground where acacia trees and plants spring out of the sandy soil.

The rays of the early-morning sun are caught in a cloud of dust stirred up by boys and girls sweeping the classrooms.

Just before the bell rings, one of the students sprints to the middle of the playground and raises the Zambian flag atop a tall pole.

These start-of-the-day rituals have become part of a new routine for two million extra children who since 2021 have been able to go to state-run schools without having to pay, because the government made schooling free for everyone.

But without enough infrastructure investment, experts say overcrowding is now threatening the quality of education, especially for low-income students.

Mariana Chirwa would not be able to go to school if she had to pay

“I stopped going to school in 2016 when I was in grade four,” says 18-year-old Mariana Chirwa donning the Chanyanya’s girls uniform, a light-blue shirt topped with a tartan bow.

“Without free education I don’t know how my parents would have managed to take me back to school. They don’t work and just stay at home.”

A poster of the class sizes hanging on the wall of the headteacher’s office spells out the challenge schools like Chanyanya face.

In one of the classrooms, 75 boys and 85 girls are squeezed into a space that would comfortably fit only 30 pupils.

“When I started in 2019 I had about 40 students, but now it’s around 100 plus, and that is just in one class,” says 33-year-old teacher Cleopatra Zulu.

“Each and every day we receive new learners because of free education. Talking one-on-one is difficult, even marking is a challenge. We have even reduced the number of subjects that we are giving them”.

Richard Banda says that with more pupils the teachers are unable to give students the same attention

The experience of pupil Richard Banda reflects this.

“We don’t learn in the same way as those times when we used to pay, there’s a little bit of a difference,” he tells the BBC.

“When we were few the teacher would explain a topic again if you didn’t understand, but now because we are many, the teacher doesn’t repeat it again. That’s the difference.”

The uptick in the number of learners is reflected across sub-Saharan Africa with more children in school than ever before, the UN children’s agency Unicef says.

But with nine out of 10 primary school students in the region still struggling to read and understand simple texts, according to Unicef, the focus for policy-makers is now shifting to the quality of the education, the hiring of qualified teachers and the physical infrastructure and resources.

“When you don’t sit properly in a classroom, that affects the way that you pay attention to teaching, the way that you write your notes," says Aaron Chansa, the director of the National Action of Quality Education in Zambia (NAQEZ), which the government consults.

"We are seeing learners getting into secondary school when they can’t read properly," he says, adding that there are problems across the country.

“In Eastern Province we have more than 100 learners in one class. This has also worsened the book-to-pupil ratio. In some instances you find one book being fought over by six or seven learners.”

The government says it is listening and taking steps to address the challenges created by making education free.

“This is a good problem,” says Education Minister Douglas Syakalima. “I’d rather let the children be in a congested classroom than in the street."

“The president launched mass production of desks, mass infrastructure-building is happening.”

Education can change people's lives but it needs to be well resourced

Zambia has invested over $1bn (£784m) in the education sector since the introduction of free education three years ago - a much-needed boost after years of decline in spending as a proportion of GDP in this sector.

The government has announced plans to build over 170 new schools and has committed to the recruitment of 55,000 new teachers by the end of 2026, of whom 37,000 have already been hired.

The move has provided fresh job opportunities, but it has also led to a shortage of accommodation in rural areas. Some teachers are reporting having to live in grass-thatched houses and share pit latrines, which are at risk of overflowing.

“When it’s the rainy season here, you don’t really want to visit us,” says Ms Zulu, who lives in the school compound and remembers being nervous about the risk of cholera during the outbreak earlier this year.

Just outside her house, a large patch of dried-up shower gel marks the spot where one of the residents bathed earlier, in the open, with privacy provided only by the darkness before sunrise.

“The houses we live in are more like a death-trap,” says Ms Zulu. “The government should do something about the houses, especially the toilets.”

Cleopatra Zulu now teaches more than twice as many pupils as a few years ago

Worried about learning outcomes, some families have quietly begun to take action.

Robert Mwape is a taxi driver based in Lusaka.

In 2022, he moved his 11-year-old son from a private, fee-paying school to a public one to take advantage of free education, but he soon came to regret the move.

“I noticed [my son’s] results began going down. So one day I decided to visit the classroom. There were too many of them. You know what young people are like - so many of them, they waste time talking. The teacher couldn’t focus the entire class.”

The following year Mr Mwape, who did not want us to use his real name, reversed his original decision. Now aged 13, his son is back at a private school.

With Zambia slowly emerging from a debt default in 2020, some experts have cast doubt over the sustainability of the free education policy.

A 2023 report from the Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis and Research says that if all eligible students take up the offer of free education, government expenditure is estimated to double, “raising questions on the commitment of subsequent governments to continue the policy”.

But the education minister says he is confident the administration can shoulder the cost.

“I don’t see [the challenge] myself. Education is the best economic policy, ” says Mr Syakalima.

Making school free is widely seen as a first step towards giving young Zambians a fair chance to a brighter future.

But the country’s experience so far shows the challenges of managing a growing number of students while trying to maintain the quality of the education they receive.

You may also be interested in:

Go to BBCAfrica.com, external for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external