Why free schools have not solved Kenya's problems

- Published

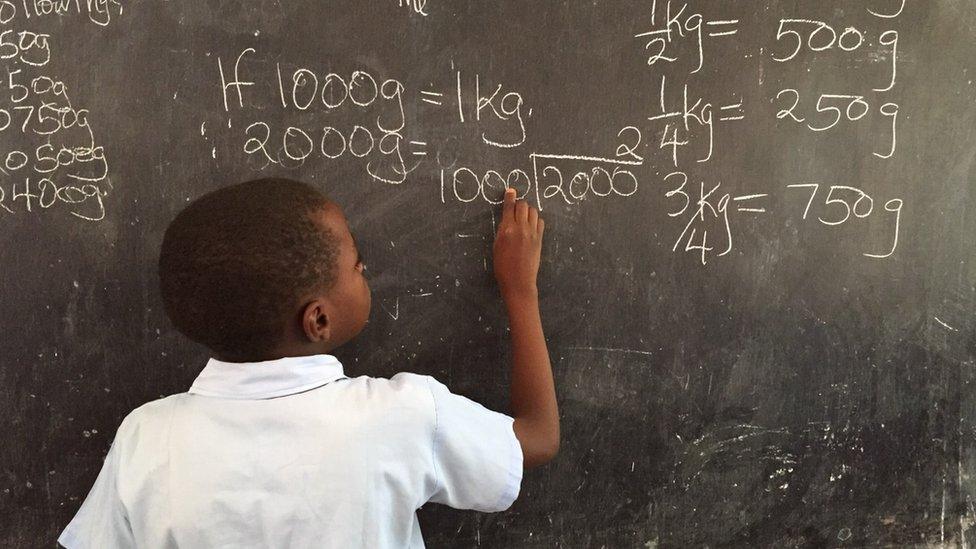

At Olympic school, one pupil works at the board as the class recites the answers in unison

Kenya has been praised for introducing free primary school education, in line with one of the Millennium Development Goals, but the country is now battling to raise education standards, as the BBC's Anne Soy has been finding out in Nairobi.

The classroom is crammed.

Four or five children squeeze into 1.5m-long wooden desks with the ones at the end forced to stretch a leg out into the aisle to stabilise them.

They are not sitting comfortably but they do seem to be concentrating on the maths lesson.

At the front one of the class is working out a conversion of grammes to kilogrammes.

The rest of them - roughly 100 11-year-olds - recite the answer in chorus.

Some classes at Olympic school have more than 100 pupils in them

The teacher walks around the classroom making sure all the pupils are on the same page of the textbook.

This is the scene at Nairobi's Olympic Primary School, which once had a reputation for high academic standards.

But when the Kenyan government introduced Free Primary Education (FPE) in 2003, the school roll almost tripled, without the facilities and resources expanding as fast.

Olympic is in the heart of the Kibera slum area, and the FPE programme gave children there a chance to get an education at no cost.

"Some classes have as many as 120 pupils in one room, handled by one teacher," headteacher Caleb Ochieng admitted.

But he said that in spite of the numbers, his school manages to perform just above average in the national examinations.

Headteacher Caleb Ochieng relies on teachers' hard work to make up for the shortfall in personnel

This is however a far cry from the days when Olympic was known as one of the best performing schools in Kenya.

Mr Ochieng said that without the teachers' hard work the standards could fall further.

"Sometimes you'll find our teachers, even when they are on the road, marking the books.

"During the weekend they are still marking so that by Monday they are done," Mr Ochieng added.

It is estimated that the country needs 80,000 more teachers to make up the shortfall in personnel.

Education Minister Jacob Kaimenyi told the BBC there have been moves to address this.

The education level of the average Kenyan pupil is way below what is expected

The government has employed 20,000 teachers in the last two years, and plans to add 5,000 more this year, but this is still not enough.

"This country spends a substantial amount of the national budget on education," Mr Kaimenyi said. "It is almost 28%, and [because of this] some people think education is overfunded."

Most of that money goes to pay teachers.

Faced with a huge shortage of both teachers and space, some schools have had to be creative.

"We converted some of the [special] rooms like the art room, home science room and the Islamic room, where Muslims were being taught Islamic studies, into classrooms," said Peter Kamau, the deputy headteacher at Nairobi's Milimani Primary School.

"Then, we employed Parent-Teacher Association [PTA] teachers, that is teachers who are paid by parents."

"We have about 10 PTA teachers, because the government cannot cope with the demand for teachers needed to implement the [FPE] programme," added Mr Kamau.

Some schools have had to be creative with their resources to fit the pupils in

Milimani School is in a middle-income neighbourhood, and most of the residents there prefer to send their children to private schools where class sizes are smaller, facilities more developed and performance in national exams generally better than public schools.

In the poorer areas, like Kibera, the government schools are vital in the effort to raise education standards.

"Most of the children here are very needy - some cannot even afford to buy a pencil," Olympic headteacher Mr Ochieng said.

The Ministry of Education says it will continue to press the finance minister for more money.

"We all believe that education is key, it's an equaliser and a basic human right," argued Minister Kaimenyi.

Flawed plan

Education researcher Sarah Ruto says many African governments have been willing to introduce basic education for all children.

But critics have argued that even though these programmes enabled more children to go to school, there was a lack of focus on the quality of education.

Ms Ruto says that Kenya performs best in East Africa for literacy and numeracy skills, but still the average pupil is below the expected level for the previous year group.

In Uganda, only 10% of the pupils can read English to the expected level.

Figure like these, Ms Ruto says, means that despite education now being available to more people there is little to celebrate.