Tears and fears as Stormont collapsed 50 years ago

Leslie Morrell is the only surviving minister from the beleaguered 1974 executive

- Published

Tears flowed inside Stormont when the first power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland collapsed exactly 50 years ago.

Outside the building, protesters celebrated as the cross-party administration fell apart on 28 May 1974.

All across Northern Ireland, there was relief that a 14-day general strike, aimed at bringing down the executive, would now end.

It was a pivotal moment in the history of Northern Ireland.

A political experiment, bringing unionists and nationalists together in power for the first time, had failed.

It was almost 25 years before it was tried again.

In the interim, more than 2,000 people died during what was known as the Troubles.

Those involved in the ill-fated executive, which began in January 1974, felt the pain personally as well as politically when power-sharing was toppled.

At their final meeting at Stormont, emotions ran high.

One of the ministers, Oliver Napier, later recalled: “Almost everybody else in that room was in tears.”

There were 11 ministers in Stormont's first power-sharing executive in 1974

The power-sharing executive was set up after the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement.

As the violence of the Troubles spiralled out of control, the UK government hoped a new devolved Stormont administration - with nationalists and unionists working together - would help restore peace.

However, IRA violence continued and loyalist paramilitaries, for different reasons, also opposed the new arrangements.

The Sunningdale deal included a Council of Ireland, which was to be set up to increase north-south co-operation.

Republicans felt the agreement did not go far enough, while loyalists believed it went too far and would lead to a united Ireland.

The largest unionist grouping, the Ulster Unionist Party, was badly split on the deal and Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was strongly opposed.

Opponents of the Sunningdale deal came together and formed the United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC).

After political attempts to bring down the executive failed, a campaign of civil disobedience led by the Ulster Workers’ Council began and the general strike in May 1974 ultimately succeeded.

A unionist demonstration at Stormont following the Ulster Workers' Council Strike

There were six unionist ministers on the executive – their leader Brian Faulkner, plus Leslie Morrell (Agriculture), Basil McIvor (Education), Roy Bradford (Environment), Herbert Kirk (Finance) and John Baxter (Information).

The nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) were represented by their leader Gerry Fitt plus John Hume (Commerce), Paddy Devlin (Health) and Austin Currie (Housing).

Mr Napier was the sole representative of the cross-community Alliance Party and was minister for law reform.

Looking back on that final meeting, he said: “Gerry Fitt cried. I remember going over to (Brian) Faulkner and putting my arm around him and saying something to the effect of that ‘I couldn’t believe that in five months that I could have the admiration for him that I had’.

“We all shook hands.

“Faulkner was very close to tears. It was a very moving occasion.”

Mr Napier, who was leader of the Alliance Party, remained in politics and was knighted in 1985.

The only minister from the 1974 executive still alive is unionist Leslie Morrell.

Leslie Morrell served as agriculture minister in the 1974 Stormont executive

Speaking at his home in County Londonderry, he recalled the day power-sharing ended.

“I wasn’t given to crying… I was upset,” he said.

“I think it was an unmitigated disaster.

“We were a good government, we were working well.

“I knew that the reason why the strike was called was because the Northern Ireland executive was beginning to show that it was successful… the people were beginning to accept it and the leaders of the UUUC knew that they had to get it stopped or their own personal political ambitions would never be fulfilled.”

'Intimidation and naked terror'

Mr Morrell, like other ministers, had to step up his personal security as tensions escalated.

He insists most people were against the strike and that it only succeeded through “intimidation and naked terror”.

Cuts to electricity supplies, roadblocks and disruption to milk deliveries brought much of Northern Ireland to a standstill.

“Paramilitaries were let loose by the politicians,” said Mr Morrell.

“I feel very sad that they were allowed to get away with it.”

Mr Morrell is very critical of the role played by Ian Paisley at the time.

Ian Paisley Snr (sixth from left) campaigning at Stormont days after the collapse

However, the late DUP leader's son, Ian Paisley Jnr, says it was right to oppose the Sunningdale agreement.

“My father not only called the situation correctly but, by his actions, was the man who saved the union from being destroyed by people who called themselves unionist," he said.

“Official unionism, as it was, never got over their defeat at that time.”

Ian Paisley Snr died 10 years ago.

Few of the key politicians from mid-1970s are still alive.

It was a turbulent time, and during the May 1974 strike the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson expressed his outrage in a TV broadcast., external

“People who spend their lives sponging on Westminster and British democracy and then systematically assault democratic methods - who do these people think they are?” he asked.

It was supposed to help the power-sharing executive but it backfired.

Mr Morrell recalls: “Even I felt insulted by it. He damned the majority for the actions of a minority.”

Three days after the prime minister’s angry remarks, the five-month-old administration at Stormont collapsed.

The headline in the Belfast News Letter the following day was: "Executive founders after 148 days at sea."

Some believed it was doomed from the start as it did not have enough unionist support.

Others said it was not given a chance to prove itself, and had it been given more time, many lives could have been saved.

One way or another, it all ended in tears.

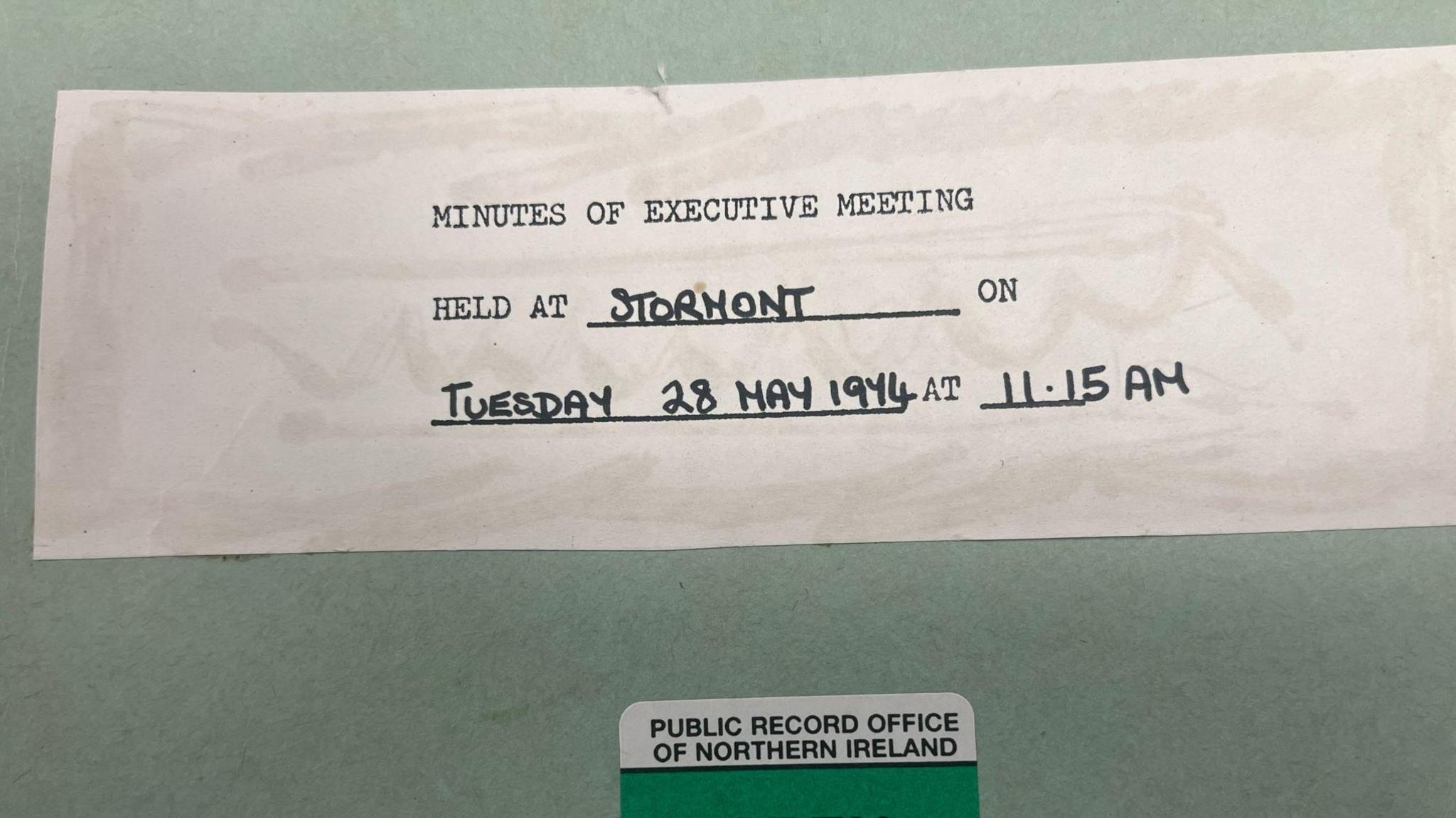

Minutes of the 1974 executive's last meeting are held by PRONI

Related topics

- Published4 February 2024

- Published10 January 2024