Starmer attempts to define 'working people' tax pledge

- Published

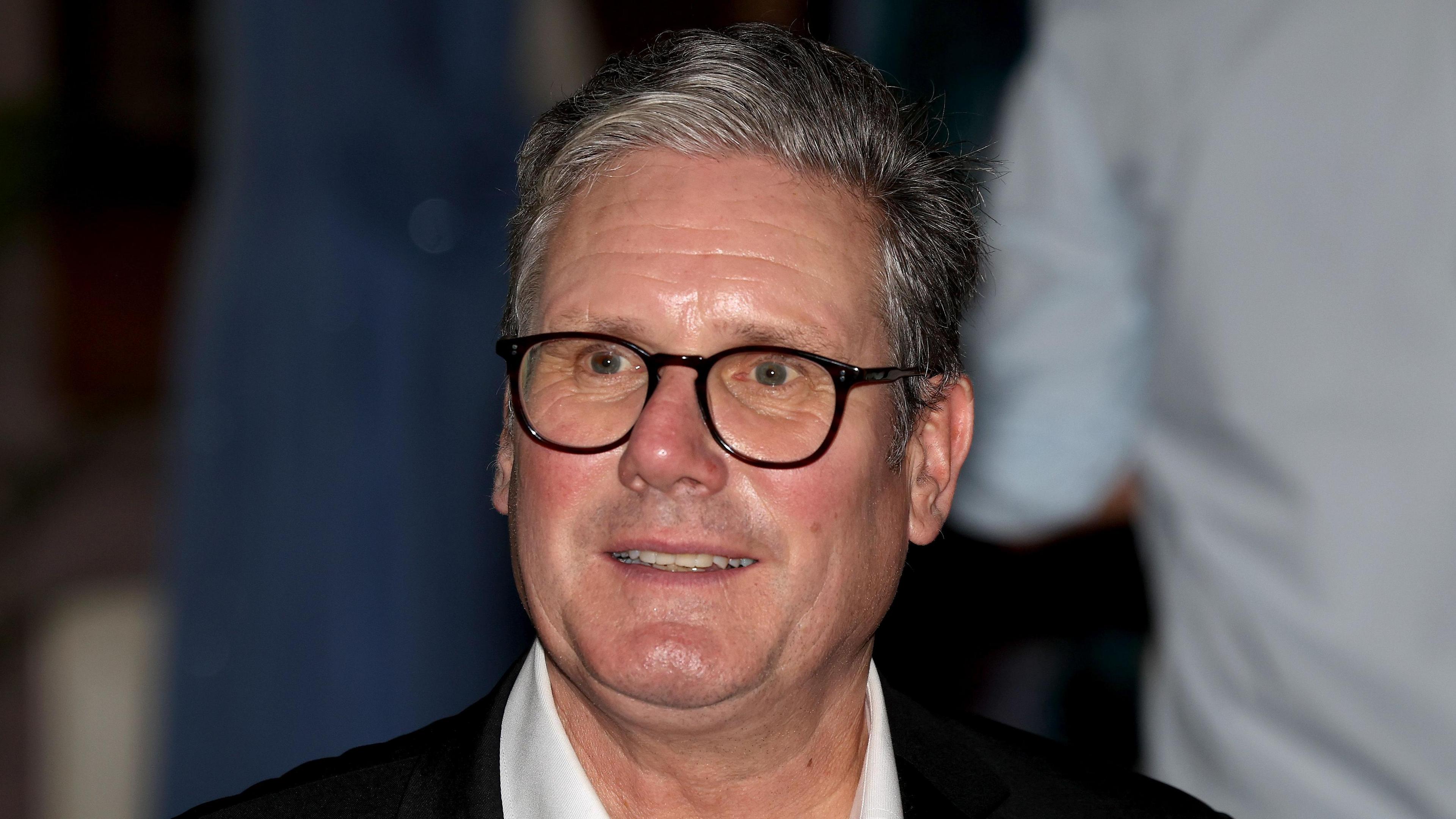

Sir Keir Starmer has attempted to define who "working people" are, amid renewed scrutiny of his tax plans ahead of next week's Budget.

Labour promised at the general election not to increase taxes on working people - but the party did not define who it had in mind.

The government is looking at increasing tax on asset sales, such as shares and property, freezing income tax thresholds, and changes to inheritance tax.

The prime minister insists working people will not be hit by these changes - but he has struggled to define who exactly he is seeking to protect from tax rises.

The Conservatives have accused Labour of "reinventing" what counts as a working person, as the Budget approaches.

When is the Budget and what might be in it?

- Published30 October 2024

Reeves eyeing £40bn in tax rises and spending cuts

- Published16 October 2024

A big week ahead and a chance for a government reset

- Published25 October 2024

In an interview during a Commonwealth leaders' summit, the prime minister was asked whether those who work, but get additional income from assets such as shares or property, would count as working people.

He replied that they "wouldn't come within my definition" - but warned against making "assumptions" about what that meant for tax policy.

He said he thought of a working person as someone who “goes out and earns their living, usually paid in a sort of monthly cheque" and who can't "write a cheque to get out of difficulties".

Speaking afterwards, his spokesman sought to clarify that those with a "small amount of savings" could still be defined as working people.

This could include cash savings, or stocks and shares in a tax-free Individual Savings Accounts (ISA), he suggested.

But ministers have been reluctant to translate these comments into numbers.

'Hypotheticals'

The prime minister accepted that his own definition was "broad".

Those people he had in mind, he added, were those who were “doing alright” but had an “anxiety in the bottom of their stomach" about making ends meet if something unexpected happened to their family.

The issue has taken on a central political importance ahead of next Wednesday's Budget, Labour's first since 2010, amid a row over whether the party is sticking to promises it made in its election manifesto.

During a BBC interview back in the UK, Treasury minister James Murray was asked repeatedly to give a more precise answer.

When asked whether someone who owned shares or sold a business could be a working person, he said he would not "get into too many hypotheticals".

"We're talking about where people get their income from," he said, adding ministers wanted to protect people who "get their income from work".

Minister asked if landlords count as 'working people'

As well as the broad pledge not to raise taxes for working people, Labour's manifesto specifically ruled out raising rates of income tax, along with National Insurance and Value Added Tax (VAT).

But ministers have not ruled out continuing to freeze income tax thresholds beyond 2028, a policy they inherited from the Conservatives, dragging more people into higher bands over time as wages rise with inflation.

And they have also not ruled out making employers pay National Insurance on their contributions to workers’ pension pots, which the Conservatives have branded a "tax on work" that will indirectly hit employees.

Labour peer Lord Blunkett, a cabinet minister in the Blair government, said the “logical outcome” of the move was that “employers will pay less".

He also cautioned that he was unsure of the government's definition of a working person, adding: "We’ve got to find a different phraseology".

Other rumoured tax rises include to capital gains tax, which is paid on profits made by selling assets including shares and property other than a main home.

The government is also planning to increase the amount of money it raises in inheritance tax, which is paid after around 4% of deaths.

Multiple changes to the tax, which currently includes several exemptions and reliefs, are under consideration.

The most recent official statistics, external show that in 2020, 11% of British households held shares in UK companies, with 12% holding stocks and shares ISAs.

According to government data from 2021, just under a third of landlords in England were full-time employees, with 1 in 10 employed part-time.

Around 15% were self-employed, whilst over third (35%) were retired.