Did the US election polls fail?

- Published

For much of the 2024 US presidential campaign, polls and pundits rated the race too close to call.

Then Donald Trump delivered a commanding victory over Kamala Harris, winning at least five battleground states, and performing unexpectedly well in other places.

He is now poised to become the first Republican in two decades to win the popular vote, and could enter office with a Republican-controlled House and Senate at his back.

So were the polls wrong about it being a tight contest?

At the national level, they certainly appeared to underestimate Trump for the third election in a row.

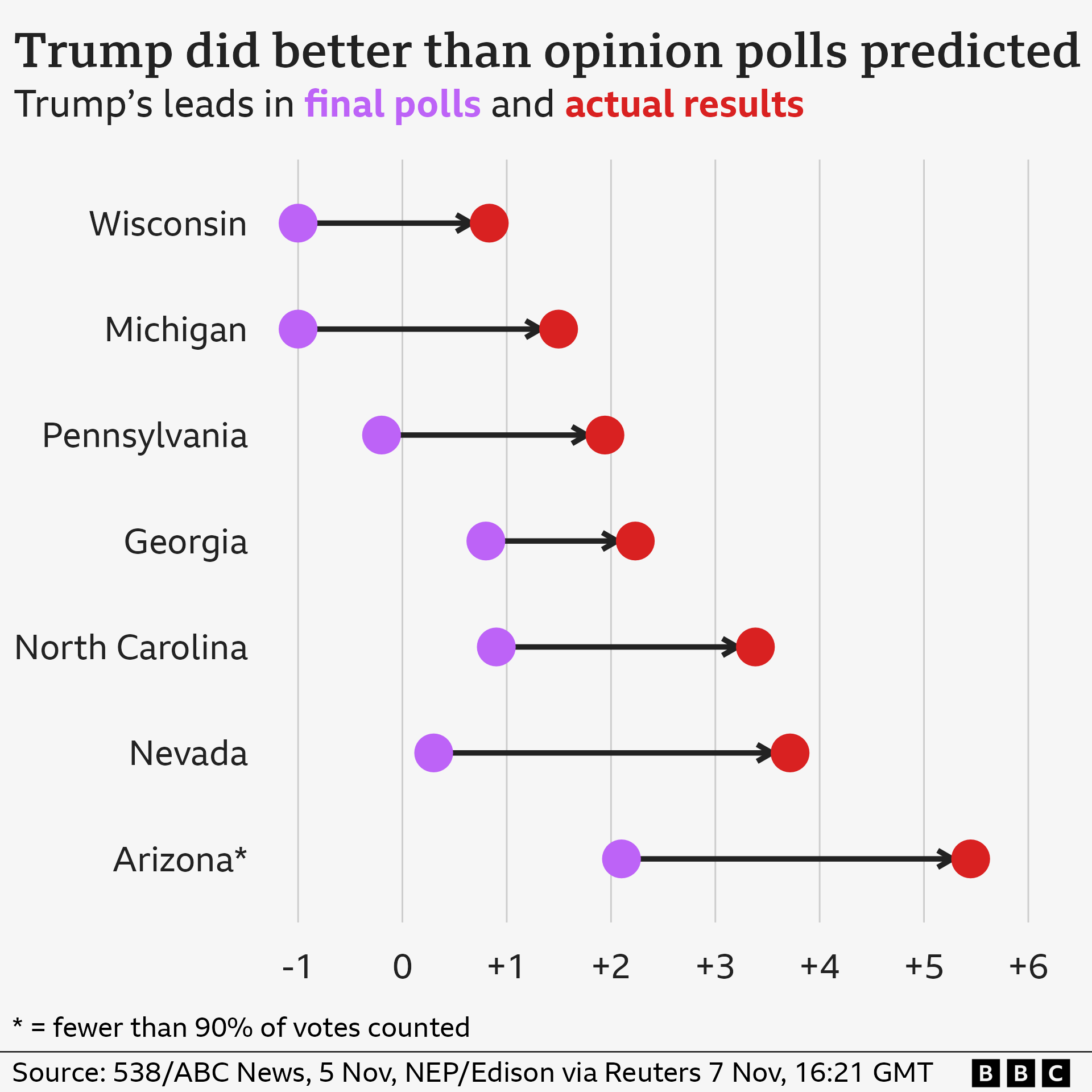

But in the battleground states such as Pennsylvania, where most of the polling was focused, Trump's margin of victory was typically within striking distance of his performance in the polls, even if the forecasts were slightly lower than the final outcome.

The average polling error seen in these swing states was not actually that big. Still, in tight campaigns, small changes can make a big difference.

Ahead of the results, media outlets including the BBC warned that despite the close race in the polls, it could end up looking like a landslide for either candidate, given the margin of error.

In some less closely-watched parts of the US, polls underestimated Trump's support more significantly - a sign of some blind spots, said Michael Bailey, a professor at Georgetown University and author of the book Polling at a Crossroads.

"At a glance, in the battleground states, polls ran a little hot for Harris but really not so bad, but when you dig deeper, it's all a little less impressive," he said.

In Florida, for example, polls tracked by RealClearPolitics in the final weeks of the election put Trump ahead by about five points. He won by a greater margin of 13.

In New Jersey, Harris was expected to win by nearly 20 percentage points, based on the two most recent polls tracked by the site. Her margin was more slender, closer to 10.

"Just imagine if we knew that or had a better sense of that a month ago. I don't know that it would change the election but it would certainly change our expectations," Prof Bailey said.

He said pollsters this year may have leaned too heavily on bets that people would behave roughly as they did in 2020 - failing to anticipate the depth of the swing among Latino and young voters toward Trump.

"These models that assume so heavily that we're going to get a repeat... they're a disaster when there's a big change," he said.

But pollster Nate Silver, founder of the 538 polling analysis site, said there were signs of peril for those who were looking.

Writing about the election results, he noted a poll from New York City last month, which indicated Trump making major inroads in the traditional Democratic stronghold.

"This is a problem the party should have been prepared for, because there was plenty of evidence for it in polls and election data," he wrote.

Debate about the polls is sure to continue in the months ahead.

That is particularly true in a year in which figures like Trump and billionaire supporter Elon Musk have promoted betting markets - many of which did forecast a decisive Trump victory - as a more accurate alternative.

Experts said the polling profession does face challenges.

Response rates to surveys have plunged, as it becomes easier for people to screen calls from unknown numbers.

The fall has also coincided with rising distrust of media and institutions - a feature particularly pronounced among Trump supporters that some argue has led to their under-representation.

Prof Bailey said the big miss in the much-discussed poll of Iowa by Ann Selzer - that was released days ahead of the election and indicated a three-point lead for Harris in the state - showed the risks of the traditional approach.

To make up for such issues, many of the most high-profile polls now function more like models, with firms weighting responses from different groups and making other assumptions about factors such as turnout.

Many pollsters have also shifted to using online surveys, but experts said those were known for being unreliable.

This year, voters who were inclined to fill out online polls were more likely to be Democrats, James Johnson of London-based polling firm JL Partners told the Times of London newspaper. They were "more likely to be young, they’re more likely to be highly-engaged, they’re more likely to be working from home," he said.

Prof Bailey said pollsters had to "move on" from random samples and get comfortable with modelling, while doing a better job testing and explaining their assumptions.

But Prof Jon Krosnick of Stanford University said without truly random samples, surveys would remain vulnerable to error.

Pollsters are "trying hard but they keep trying to be too clever," he said. "What we need to do is go back to basics and spend the time and money that it takes to do polls accurately."

North America correspondent Anthony Zurcher makes sense of the race for the White House in his twice-weekly US Election Unspun newsletter. Readers in the UK can sign up here. Those outside the UK can sign up here.