Coastlines in danger even if climate target met, scientists warn

- Published

The world could see hugely damaging sea-level rise of several metres or more over the coming centuries even if the ambitious target of limiting global warming to 1.5C is met, scientists have warned.

Nearly 200 countries have pledged to try to keep the planet's warming to 1.5C, but the researchers warn that this should not be considered "safe" for coastal populations.

They drew their conclusion after reviewing the most recent studies of how the ice sheets are changing - and how they have changed in the past.

But the scientists stress that every fraction of a degree of warming that can be avoided would still greatly limit the risks.

The world's current trajectory puts the planet on course for nearly 3C of warming by the end of the century, compared with the late 1800s, before humans began burning large amounts of planet-heating fossil fuels. That's based on current government policies to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels and other polluting activities.

But even keeping to 1.5C would still lead to continued melting of Greenland and Antarctica, as temperature changes can take centuries to have their full impact on such large masses of ice, the researchers say.

"Our key message is that limiting warming to 1.5C would be a major achievement - it should absolutely be our target - but in no sense will it slow or stop sea-level rise and melting ice sheets," said lead author Prof Chris Stokes, a glaciologist at Durham University.

The 2015 Paris climate agreement saw the world's nations agree to keep global temperature rises "well below" 2C - and ideally 1.5C.

That has often been oversimplified to mean 1.5C is "safe", something glaciologists have cautioned against for years.

The authors of the new paper, published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment, external, draw together three main strands of evidence to underline this case.

First, records of the Earth's distant past suggest significant melting – with sea levels several metres higher than present - during previous similarly warm periods, such as 125,000 years ago.

And the last time there was as much planet-warming carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as today - about 3 million years ago - sea levels were about 10-20m higher.

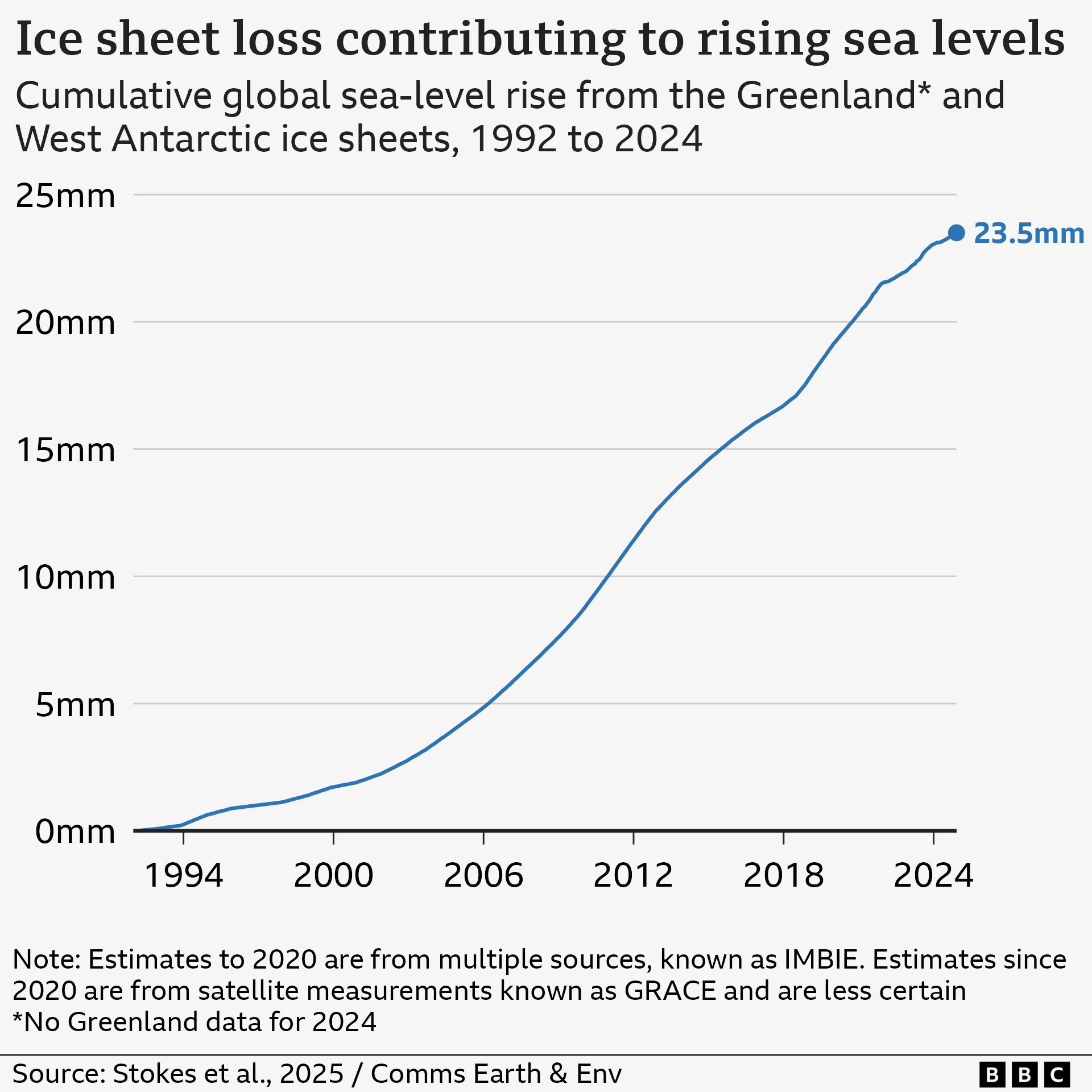

Second, current observations already show an increasing rate of melting, albeit with variation from year to year.

"Pretty dramatic things [are] happening in both west Antarctica and Greenland," said co-author Prof Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre.

East Antarctica appears, for now at least, more stable.

"We're starting to see some of those worst case scenarios play out almost in front of us," added Prof Stokes.

Finally, scientists use computer models to simulate how ice sheets may respond to future climate. The picture they paint isn't good.

"Very, very few of the models actually show sea-level rise slowing down [if warming stabilises at 1.5C], and they certainly don't show sea-level rise stopping," said Prof Stokes.

The major concern is that melting could accelerate further beyond "tipping points" due to warming caused by humans - though it's not clear exactly how these mechanisms work, and where these thresholds sit.

"The strength of this study is that they use multiple lines of evidence to show that our climate is in a similar state to when several metres of ice was melted in the past," said Prof Andy Shepherd, a glaciologist at Northumbria University, who was not involved in the new publication.

"This would have devastating impacts on coastal communities," he added.

An estimated 230 million people live within one metre of current high tide lines.

Defining a "safe" limit of warming is inherently challenging, because some populations are more vulnerable than others.

But if sea-level rise reaches a centimetre a year or more by the end of the century - mainly because of ice melt and warming oceans - that could stretch even rich countries' abilities to cope, the researchers say.

"If you get to that level, then it becomes extremely challenging for any kind of adaptation strategies, and you're going to see massive land migration on scales that we've never witnessed [in modern civilisation]," argued Prof Bamber.

However, this bleak picture is not a reason to stop trying, they say.

"The more rapid the warming, you'll see more ice being lost [and] a higher rate of sea-level rise much more quickly," said Prof Stokes.

"Every fraction of a degree really matters for ice sheets."

Additional reporting by Phil Leake

2024 first year to pass 1.5C global warming limit

- Published10 January

Is the UN warning of 3.1C global warming a surprise?

- Published24 October 2024

World's glaciers melting faster than ever recorded

- Published19 February

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.