What is the Paris agreement and why does 1.5C matter?

- Published

In Paris in 2015, almost 200 countries signed a landmark agreement designed to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

One key aim was to try to limit future global temperature rises to 1.5C above "pre-industrial" levels.

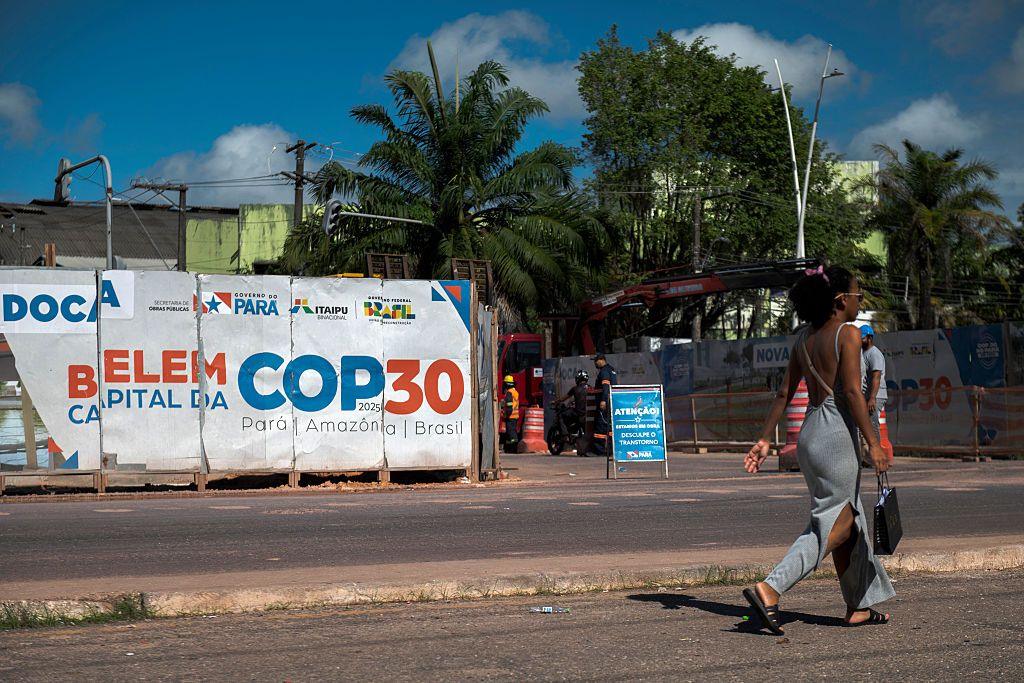

However, ahead of the COP30 meeting in Brazil in November 2025, UN secretary general António Guterres has said that overshooting that target is now "inevitable".

What is the Paris climate agreement?

The Paris agreement is at the heart of the international commitment to tackle rising global temperatures.

It came into force on 4 November 2016 and saw almost all the nations of the world agree to cut the greenhouse gas emissions which cause global warming.

However, US President Donald Trump has once again vowed to withdraw from the deal.

Trump pulled the world's second biggest greenhouse gas emitter out of the Paris accord during his first US presidential term.

The US rejoined in 2021 under his successor President Joe Biden.

Leaving again would mean the US would rejoin Iran, Libya and Yemen as the only countries outside the agreement.

What does the Paris agreement say?

The Paris agreement lists a series of commitments:

to "pursue efforts" to limit global temperature rises to 1.5C, and to keep them "well below" 2.0C above those recorded in pre-industrial times, generally considered to mean the late 19th Century

to achieve a balance - known as net zero - between the greenhouse gases that humans put into the atmosphere and the gases that they actively remove, in the second half of this century

each country to set its own emission-reduction targets, reviewed every five years to raise ambitions

richer countries to help poorer nations by providing funding, known as climate finance, to adapt to climate change and switch to renewable energy

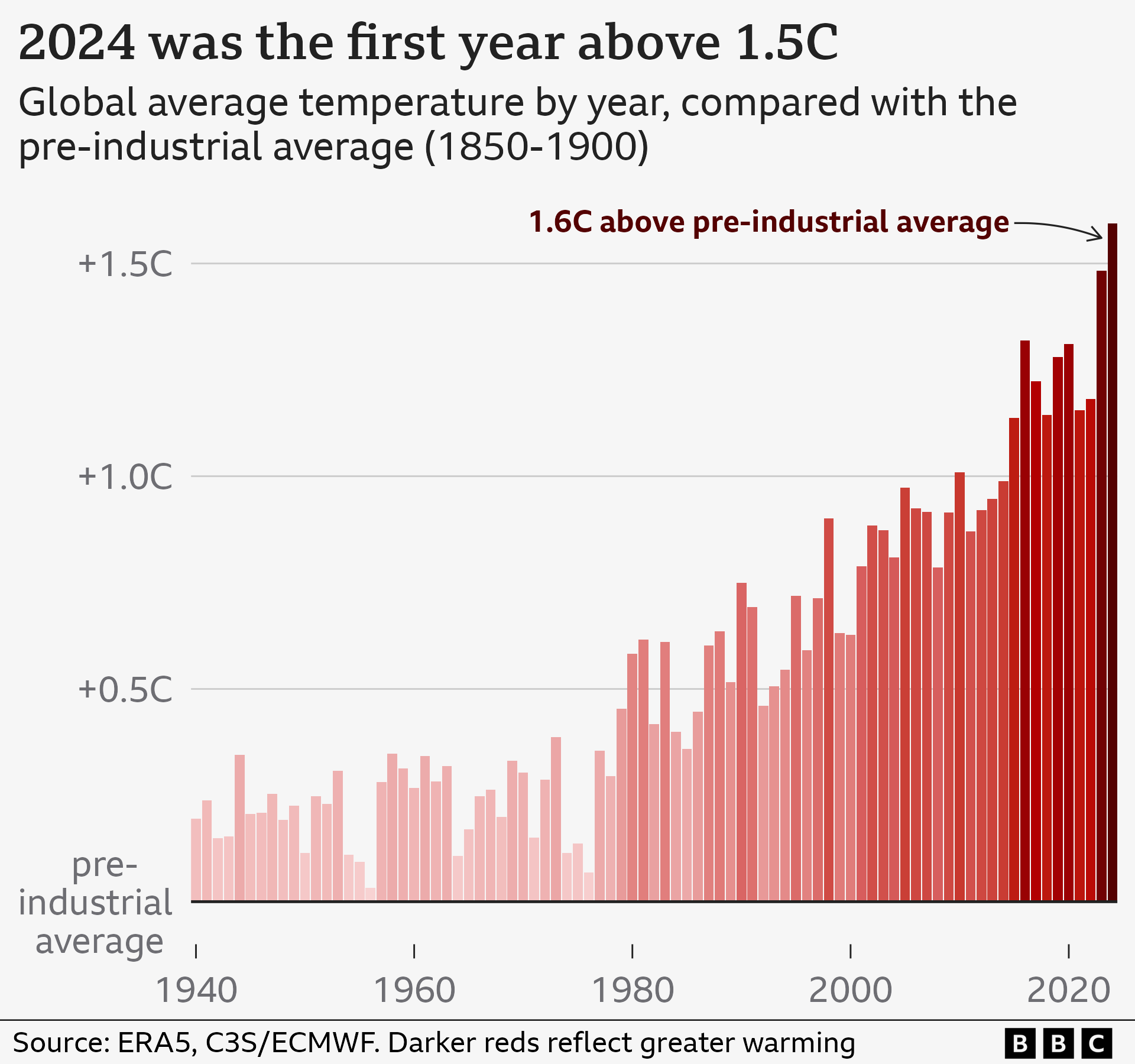

The 1.5C target is generally accepted to refer to a 20-year average, rather than a single year.

So, while 2024 was more than 1.5C warmer than pre-industrial times, it did not mean the Paris agreement threshold has been breached.

Why does keeping global warming to 1.5C matter?

Every 0.1C of warming brings with it greater risks for the planet, such as longer heatwaves, more intense storms and wildfires, according to climate scientists.

But a very large body of scientific evidence shows that warming of 2C or more would bring far greater impacts, on top of those felt at 1.5C, UN scientists say.

These include:

more people being exposed to extreme heat

higher sea levels as glaciers and ice-sheets melt

increased risks to food security in some regions due to more extreme weather

greater chances of some climate-sensitive diseases spreading, such as dengue

more species being threatened with extinction

the loss of virtually all coral reefs

Some changes could become irreversible if so-called "tipping points" are crossed.

It is not clear exactly where these sit, but once these thresholds are passed, changes could accelerate and become irreversible.

These could include the collapse of the Greenland Ice Sheet, warm Atlantic Ocean currents or further loss of the Amazon rainforest.

A really simple guide to climate change

- Published29 October

What is net zero and is the UK on track to achieve it?

- Published5 November

What does the Paris agreement promise for poorer countries?

The Paris deal restated a 2009 commitment that richer countries should provide $100bn (around £77bn) annually by 2020, to help developing nations deal with the effects of climate change, and build greener economies.

Although only $83.3bn was raised in 2020 itself, data from the OECD, external shows the goal was eventually achieved in 2022.

In 2023, countries agreed for the first time that a fund should be established exclusively for loss and damage. This is money to help countries recover from the impacts of climate change.

At COP29 in 2024, richer nations committed to providing $300bn (around £230bn) a year to developing nations by 2035. Developing countries - which had hoped for more - criticised the "paltry sum".

What has happened since the Paris agreement?

World leaders meet every year to discuss their climate commitments at international summits known as COPs (Conference of the Parties).

All COPs since 2015 have tracked how countries are building on what they promised in Paris.

At COP28 in 2023, countries agreed for the first time to "contribute" to "transitioning away from fossil fuels", although they were not forced to take any specific action.

However there was no significant progress on this goal at COP29 the following year.

Is the world on track to meet the 1.5C target?

The long-term 1.5C global warming target has not yet been breached.

But based on current rates of warming, the world could pass 1.5C around the year 2030.

"One thing is already clear: we will not be able to contain the global warming below 1.5C in the next few years," UN secretary general António Guterres said in October 2025.

His statement followed news that less than a third of countries had submitted new national pledges for cutting carbon emissions, as required ahead of November's COP30 climate summit.

Combined, these plans would not succeed in limiting warming to 1.5C.

However, Mr Guterres said that he hoped temperatures could still be brought back down to the 1.5C target by the end of the century.

Sharp cuts to emissions can still make a major difference to future warming and the impacts of climate change, scientists say.

- Published7 November